Behind the macro-level statistics: The role of resilience in informing financial health in Mexico

The decision to close his footwear store was one of the toughest José had to make in his 35 years of operating his business just outside of Mexico City. With most of his family’s funds tied up in inventory, suppliers calling on stock purchased on credit, and no other stable family cash flow, José didn’t have many options. Closing the shop just three weeks after the Mexican government announced measures to slow the spread of COVID-19, José and his family had to make do with the little savings they had kept at home. As he watches policymakers on television discuss how and when to open up the economy, José sends out a plea to his extended family for support to weather the coming storm.

A five-hour drive southeast of José’s shop lives his niece Elena, a 28-year old mother of two with a strikingly different financial health starting point before the pandemic. Elena and her three closest friends in Oaxaca are members of Acreimex, a local cooperative where she maintains a modest savings account and routinely borrows to fill the working capital needs of her small grocery store and informal restaurant. While she lives in a single home with many more people under one roof – four adults and three children – than her uncle José, she has been able to lean on her sister’s stable salaried job and a moderate remittance from a brother in the U.S. to weather the initial shifts in demand at her shop and restaurant due to COVID-19 restrictions. There isn’t as much money to go around these days and, consequently, they have had to cut back on spending, but Elena and her family are cautiously optimistic about the future.

The stories of José and Elena are being played out globally through the pandemic and provide us with an opportunity to examine the role of financial health in protecting and building the resiliency of low-income individuals. While most international media coverage focuses on how the pandemic has exposed weaknesses in the resiliency of our healthcare systems and economies, there are millions of people like José and Elena that are the human faces behind these macro-level statistics and trends. Their stories provide insights into how people and communities are impacted at a micro-level. We must take the time to understand the tools they use to navigate the crisis and why, which informs how we can respond as a sector.

For BFA Global and our FinnSalud program supported by MetLife Foundation in Mexico, resilience has a specific meaning. It refers to possessing specific financial means to protect a household and a livelihood against unforeseen shocks. In particular, we look at an individual or households’ preparedness for unanticipated shocks, their available and accessible coping strategies, the effectiveness of these strategies, and their length of recovery after a shock.

With this in mind, BFA Global deployed three rounds of a COVID-19 and Financial Health rapid dipstick survey with 5,439 consumers and 1,271 micro- and small enterprises (MSEs) in ten markets (Nigeria, Kenya, South Africa, Ghana, India, the US, the UK, Mexico, Vietnam, and Zambia) over the first four months of the pandemic (March-June 2020).

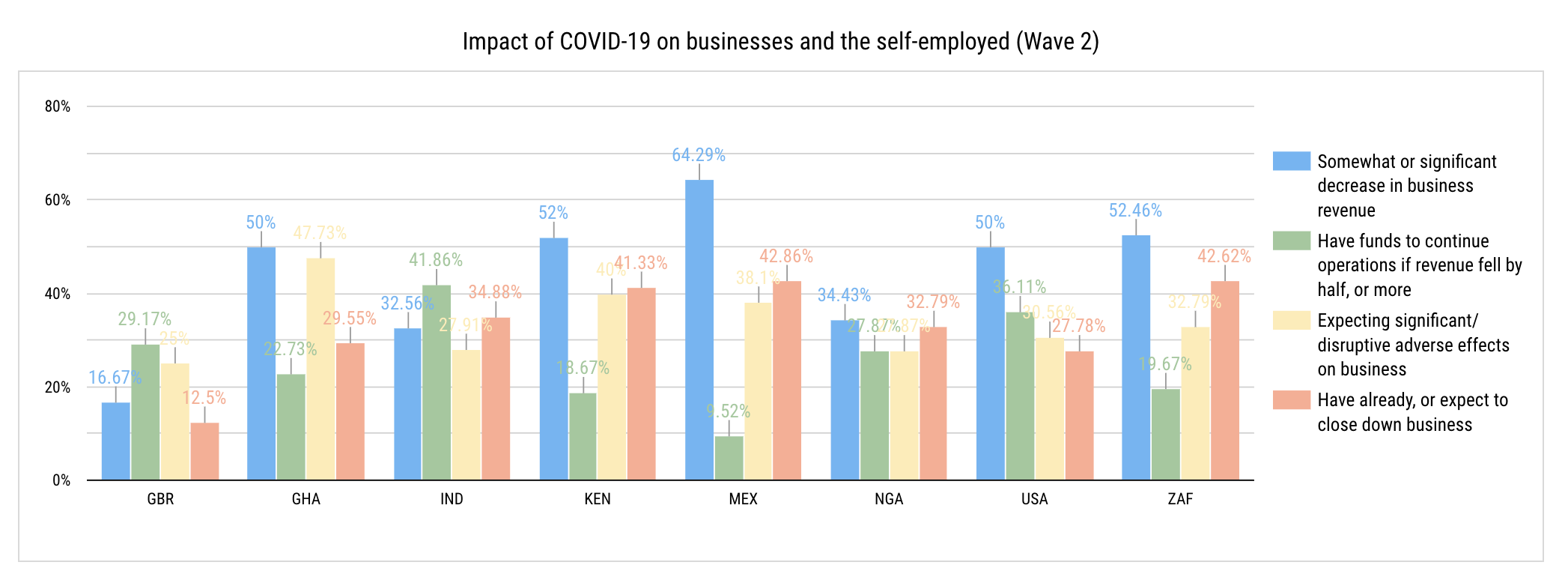

This research in Mexico indicates that José is not alone in how the pandemic response has impacted income and expenses at the household level and in small businesses. By the second wave of interviews, incomes were down for 64% of MSEs and self-employed individuals. The decline in revenue had caused many businesses (42%) to close or expect to do so.

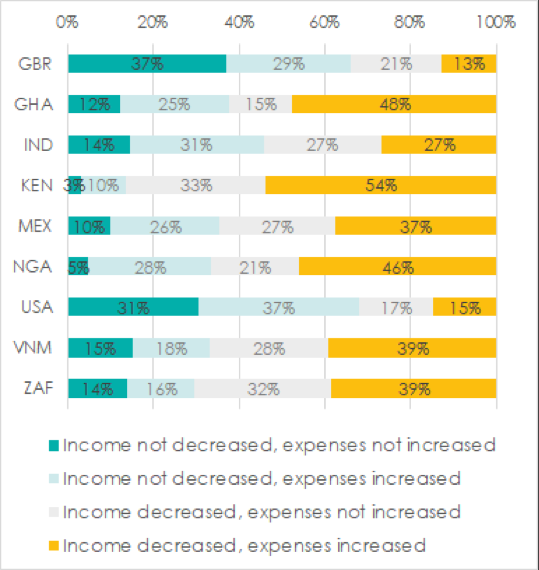

By wave 3 (May 2020), nearly 40% of respondents in Mexico continued to face the dual pressures from declining incomes and rising expenses; an additional 27% reported decreased income but not rising expenses.

With minimal coping mechanisms available, José was forced to shut down his shoe shop and liquidate a large portion of his inventory at a loss. For others, the dual pressure of lowered or disrupted incomes and rising expenses can lead to challenges in repaying loans, a need to liquidate assets or draw down available savings, or to pursue loans from pawnshops or loan sharks.

However, we also see that those people like Elena, who began with a few core resilience tools, have been much better able to respond. In particular, we found that the most effective resilience tools tend to be a mix of cash emergency funds, insurance, and other types of support. Our questionnaire measured how many respondents held non-cash assets (such as gold and livestock); insurance to protect health, assets, homes, and businesses; and supportive social networks that can be leaned on in challenging times.

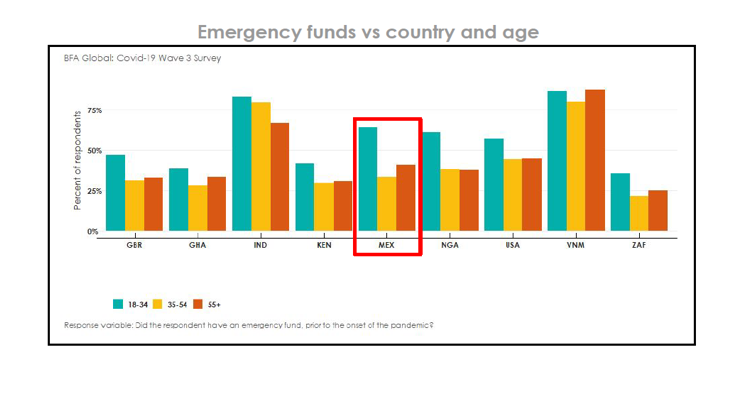

With a modest savings account, Elena is part of a generational shift in savings behavior observed in Mexico. Almost twice as many young respondents (18-34) reported setting aside money compared to 35-54 year olds. Also, fewer young people used these emergency funds. In Ghana and other African countries, high proportions of respondents reported more than half or “all” of the emergency funds were spent, particularly among older populations. In Mexico, by contrast, two-thirds of youth (under 35) reported having spent “none” or less than half of their emergency funds.

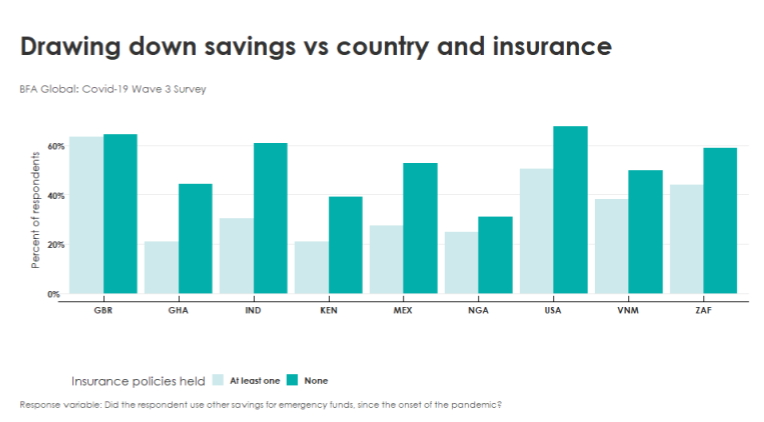

Access to insurance is also an important factor. Respondents were more likely to set aside funds for a specific purpose when they held at least one type of insurance, suggesting some combination of wealth and financial knowledge driving both behaviors. The uninsured were more likely to report having used funds intended for other purposes to get through a crisis.

We also found that the availability and strength of social networks made a difference, with the ability to leverage relationships for new income opportunities, as a source of borrowing, or a source of higher than normal remittances during the pandemic lockdowns. Resilient respondents also have higher control over their financial decisions and were able to negotiate a break on loan installment payments and other financial obligations. In Elena’s case, she negotiated an extension on an inventory loan from a food supplier she has known since childhood and made up some of the cash flow shortfall with direct transfers from her brother in New York.

The “COVID-19 and Your Financial Health” survey allowed us to understand what happened to the financial lives of people in Mexico and how they responded to the crisis. With data from similar profiles in other markets, we examined what might be unique about the Mexican context. We followed up this quantitative work with a cohort study with members of Cooperativa Acreimex and Caja Popular Atemajac – the two partner financial cooperatives of the Finnsalud project. Over the same April-June timeframe, we conducted bi-weekly phone interviews with members of both cooperatives to understand the progression of financial effects of the crisis in their lives, learn about their coping strategies and resilience mechanisms, and the drivers of their behavior.

As the lockdown measures progressed over April and May, respondents experienced reduced mobility, which in turn led to lower incomes due to reduced stock or sales made on consignment, the disappearance of sales channels, and, in some cases, the closing of businesses that relied on rented spaces. In some households, we saw sustenance shift to those members of the family with a formal, fixed income job. At both the business and household levels, the primary coping strategies included:

- Reduced expenses wherever possible – Most respondents focused on reducing non-essential expenses or shifted to purchasing lower-cost alternatives (i.e., firewood instead of cooking gas). If a shop was able to keep the doors open, the enterprise had to adjust to much lower foot traffic by reducing working hours, laying off non-family staff, and lowering prices.

- Changed consumption habits – At home, families rationed food and tilted purchases toward the basics. In some cases, this required a shift in protein consumption (from meat to chicken, or from chicken to egg or cheese) and opportunistic shopping when, for example, produce prices were reduced.

- Shifted resources to generating income – In addition to expenditure and consumption habit changes, respondents took urgent action to generate supplementary income. Many respondents turned to food preparation and sale; one member sought a loan from an informal lender and a few requested government assistance.

In response to the COVID-19 crisis, cooperatives in Mexico supported their members as best they could. They were allowed by the regulator to offer loan payment deferrals and grace periods to their members for four months. Additional flexibility measures were announced at the end of October, enabling cooperatives to offer supplementary restructuring and renewal terms to their members only if these can be proven to result in financial benefit for borrowers. These measures are a lifeline for small businesses that have seen revenues fall off a cliff in the past few months.

The cooperative sector has an important role to play in building and strengthening member resilience. They are mindful of the profound changes that the pandemic and resulting economic shocks have imposed on their membership. As José and Elena’s stories illuminate, resilience is a core component of financial health that should be prioritized by financial institutions and policymakers. We hope that, through targeted interventions, the resilience of Mexican households can be measurably strengthened going forward. Through FinnSalud, we plan to help financial institutions measure their customers’ financial health and develop initiatives that enhance it. We will be sharing the progress of our work in this space in future blogs.