Building Inclusion Into the Investment Process: Four Steps for Addressing Bias Against Women Startup Founders

Originally published in NextBillion

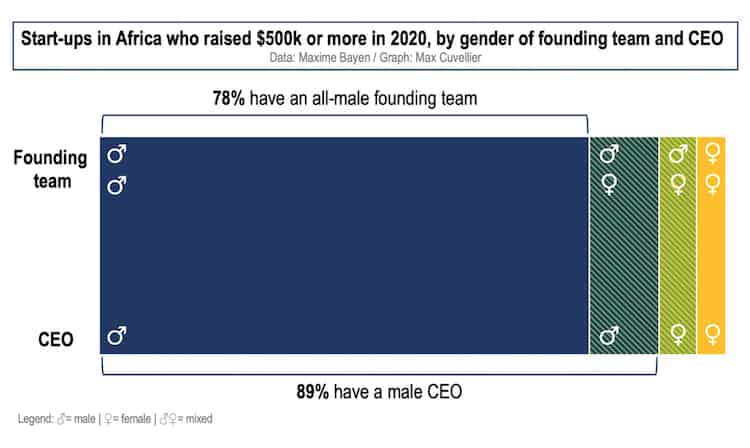

Contrary to pessimistic expectations at the outset of the COVID pandemic, global funding for startups grew in 2020. Unfortunately, this growth did not include women founders, who experienced a steep 27% decline in investment compared to the previous year. Funding for women founders was low to begin with, especially in emerging markets; in 2019 only 11% of seed funding in emerging markets went to companies with a woman on their founding team. While 2019 broke records globally, with 21 new female-founded unicorns and an upward trend in labor force participation, 2020 rolled back this progress, and women founders only secured 2.2% of venture capital funding globally.

Root causes of these drops include uneven distribution of childcare and household tasks, but also sexism among investors. Globally, one-third of female entrepreneurs report facing gender bias from investors — but this number doesn’t capture the true extent of the problem, as sexism is both explicit and implicit.

Explicit sexism, in which sexist beliefs are outwardly expressed, may be easier to recognize and (hopefully) eliminate. This can include everything from refusing to invest in women with children or plans to have children to outright sexual harassment to sending lower-level investment staff to evaluate women-led startups. As one female founder/CEO described it, in an anecdote that’s all too familiar, a VC partner she encountered “admitted he always sends a junior 20-something trainee to interview the female founders but is inclined to send someone more senior to male founders.”

However, implicit sexism is built into processes and culture and may be harder to root out. For example, the belief that women’s markets and products are less profitable than others (e.g., Spanx, The Mom Project) or that women are less capable of leading in male-dominated industries, may be harder to recognize or identify — but such underlying beliefs undoubtedly drive the gender gap in investment.

Although the overall investment picture is dispiriting, members of the startup and tech communities have recognized the problem and are working to address it. These efforts remain small and localized in specific funds and programs, so much more effort is needed to achieve progress.

At Catalyst Fund, our efforts to consciously source and support more women founders resulted in a cohort in which five out of six startups are led by women founders/co-founders. As we set out to recruit women founders, we spoke to two female venture capitalists, Lexi Novitske from Acuity Ventures and Lelemba Phiri from Enygma Ventures, to understand how they are thinking about the gender funding gap. In our conversations, we identified four changes to the investment funnel that can greatly impact the funding landscape for women founders. Below, we’ll discuss some of the insights they shared.

STEP 1: CONSIDER NETWORKING AND DEAL-SOURCING BIAS AT THE TOP OF THE FUNNEL

Venture capitalists tend to rely on introductions and references to build their pipeline because the intuition and intelligence within social networks are invaluable for recognizing talent and potential. In fact, Catalyst Fund’s Investor Advisory Committee (IAC) was built on exactly these principles. Our IAC comprises six investors — Accion Venture Lab, Flourish Ventures, Gray Ghost Ventures, Anthemis, Quona Capital and Better Tomorrow Ventures — each of whom nominates a startup to our cohort. This investor-led sourcing model allows us to rely on the expertise of our investors in the markets where they operate so we can identify the most promising fintech startups for Catalyst Fund.

Unfortunately, depending on social networks for referrals also means those referrals will likely come from a constant pool of people who share characteristics and demographics. As has been noted by VCs, “Pattern-matching, when based on closed, insular networks, only begets much of the same: insular, exclusionary patterns…” More specifically, this means that founders outside the normal profile — particularly, women — are often excluded from referral funnels.

To address these exclusionary funnels, Phiri asks: “What pond are you fishing in?” Some VCs have gone so far as to suggest that venture capital should ban the third-party, network-driven referrals known as warm introductions in an effort to short-circuit pattern matching. Novitske notes that eliminating events, like late-night networking, that are less friendly for women and mothers (who shoulder the bulk of the childcare burden) can help women access opportunities. To truly support founder diversity, it’s important to vary these “ponds” and not depend on existing social networks and events, which are typically crafted by and for men.

Novistke notes, “I have to personally seek female founders,” while admitting that getting referrals still remains one of the best ways to source power-packed startup teams. At Catalyst Fund, simply highlighting women founders as our priority for this cohort enabled us to better identify more women-led startups, even while leveraging referrals from our existing network.

Phiri also suggests that making initial outreach more inviting for founders can encourage more women to engage. As has been anecdotally noted, women tend to undervalue themselves thanks to the confidence gender gap, so messaging, such as open calls, event applications, or public announcements, that may be perceived as competitive can be discouraging. This may explain why women less frequently apply or participate in competitions and pitch days. GALI data shows that of the roughly 15,000 applications received by accelerator programs, those from solely female founders represent only 13% of the pool. Using language that is less intimidating, such as “inviting” female founders to participate instead of asking them to “apply,” could help, as could crafting more collaborative opportunities for participation, such as workshops or mentorship programs.

Other women-focused investors note another bias against specific product areas and sectors that tend to see more women founders, for instance, wellness, child-oriented or femtech startups. It can be worthwhile, for instance, to look beyond “fancy tech plays” (like AI startups) that typically attract more investment dollars. Both Novitske and Phiri note that they’ve found women are more likely to build solutions that may leverage only a simple layer of e-commerce or SMS tech, for example, but their impact can be just as high. It’s vital that investors and accelerators consider these solutions as viable business models during screening, rather than dismissing them as less innovative purely based on the level of technology.

STEP 2: ADJUST PITCHING, DUE DILIGENCE AND INVESTMENT DECISION PROCESSES

Even a strong pipeline of female founders does not guarantee more will get funded. As mentioned above, pattern matching can disadvantage women, though some investors consider such shortcuts and bias critical to their “secret sauce.”

During investment committee meetings, a number of other biases may surface. Studies have shown how women’s voices and more measured pitching style can impact investment decisions even when the business model remains unchanged. For instance, men are often asked more “promotion” questions to highlight upside and potential gains, whereas women find themselves answering more “preventive questions,” such as explaining their potential losses or risk mitigation strategies, or when they might break even.

Furthermore, given men’s greater access to mentorship, they are more likely to be prepared for investment committee environments: Around 48% of women cite a lack of available mentors as a factor that is holding them back when it comes to growing their businesses. One way investors can try to level the playing field is by sharing investment committee questions and formats ahead of time with founders so they can better prepare. Committees can also consider appointing an advocate from within the group to serve as a guide and mentor for women founders as they approach the process.

Phiri’s advice to female founders is to not overemphasize the impact side of their business and to give importance to revenue metrics while avoiding getting pigeonholed into the micro calculations. She noticed that when startups are impact-oriented, it’s easy for founders to let their passion for the social benefits guide their startup’s story. Her advice is to remember that VCs are looking to invest in startups with the potential to exponentially scale, not just social businesses. So while the impact story is a unique selling point, there’s also the need to tell the business story.

One strategy that’s being employed by organizations including Catalyst Fund is a pitch-less investment process. At Catalyst Fund, investment decisions exclude any influence of founder charisma. Our team only shares tearsheets with our investment committee, which place emphasis on the startup’s business model, the market opportunity and the team’s ability to address the problem they’re trying to solve. Our tearsheets also include a specific assessment of the startup team’s diversity, and they award additional value to teams with women and local founders. This approach to place initial emphasis on diversity and inclusion is becoming more popular, as a recent HBR article noted how using environmental, social and governance assessments can make factors like gender and climate impact a part of initial screening.

After calls with several female founders, referrals from our Circle of Investors, targeted sourcing from our IAC and efforts to highlight our existing female founders, we now stand at 23% female founder representation (compared to our earlier 13.5% across Catalyst Fund cohorts). While it’s certain there’s more to be done, we are better equipped to source female founders through these networks, and we understand that it is possible when you set targets and commit more intentionally.

STEP 3: APPOINT WOMEN TO INVESTMENT TEAMS AND FUND MANAGEMENT

Another factor contributing to investment bias is the lack of racial and gender diversity in decision-making positions within VC firms. Fairview Capital found that “diverse managers invest in diverse founders, who hire diverse employees.”

However, hiring women investors is not a simple solution to implement, even in the impact and foundation worlds. As a recent SSIR article notes, “Many foundations require that fund managers have a track record of investing with the same strategy at the same company stage. However, we know that very few diverse fund managers have been let into mainstream firms to acquire attributable track records… If mainstream firms shut out diverse fund managers or won’t let them port their investment track records to new firms, we have to ask how women and people of color are supposed to obtain track records in the first place.”

Novitske says that setting internal hiring targets and publishing those targets is one way to increase representation on the team. This is also her advice to other investment firms, though she says that setting internal targets is not enough; firms need to be held accountable for inclusion, which could happen via publicly stated commitments to specific targets.

Both Phiri and Novitske agree that limited partners have a huge role to play in supporting women investors, as they are shaping the startup ecosystem in Africa and other frontier markets: Their push from the governance side could be what moves the needle for including more women in investment firms.

STEP 4: ENCOURAGE WOMEN’S LEADERSHIP AND NORMALIZE FAILURE

Novitske believes in letting the “data speak for itself,” which extends to women’s leadership in her portfolio companies; after all, companies with women at the C-level have statistically higher net margins. Both Novitske and Phiri say they take a close look at team composition to evaluate diversity and assess the distribution of equity compensation among co-founders. If they find misalignment with their expectations, they make it a priority in their value creation plan with the startup and push hard for better representation.

Supporting women leaders can also mean normalizing their failures. “Currently, there’s a higher social penalty for women who fail at building a business,” says Phiri. Success stories are not an everyday reality — even less so in emerging markets, particularly in social impact sectors. There is a need for market enablers to normalize failure stories for men and women.

Finally, investors can consider extending support outside of their portfolio to help women founders become investment-ready. “At some level, it is up to investors to walk that journey with an entrepreneur, even if they are not going to invest,” says Phiri. According to her, female entrepreneurs are less exposed to constructive criticism, and investors can play a role in providing them this feedback and guidance.

CONTINUED COMMITMENT

Catalyst Fund works with startups on their investment readiness during venture building and tailors this support based on a startup’s identified areas for growth and expertise. From our unique vantage point between startups and investors, we hope to facilitate better channels of communication, and to build expectations that can serve to benefit women founders in particular.

We’re also starting to look into systemic causes that result in fewer women in tech, and considering how we might help address those through the Catalyst Fund Inclusive Fintech Talent Program, which helps young professionals kick-start their careers in tech. We see this work as part of our ongoing commitment to bringing greater inclusiveness to our own investments — an approach we hope will become the norm across the broader sector.