Spazas and informal trade are excluded from COVID-19 relief efforts in South Africa

As the Coronavirus pandemic unfolds around us, South Africa has been lauded for taking an aggressive approach to control. As of this past weekend, South Africa had recorded ~2,300 confirmed cases and 25 deaths. The country implemented a complete 21-day shutdown from midnight on March 26th, which was extended by another 14 days. The government has enacted measures restricting movement and gatherings for citizens and has closed schools and non-essential businesses. Flights are suspended, all commuter rail services are shut down, and public minibus taxis are only allowed to transport essential service workers. Individuals are not allowed to leave their homes except to seek medical care, buy food, medicine, and other supplies, or to collect a social relief grant. The implications of this lockdown for informal traders and spaza shops (informal fast-moving consumer goods retailers) will be dire, which in turn will mean difficult times for low-income workers and consumers living in townships.

Stakeholders have recognized the vulnerability of small businesses and have launched relief efforts to sustain them. However, the requirements for these funds are overly stringent and exclude informal traders in townships that serve as a critical lifeline for South Africa’s most vulnerable people.

Informal trade and spaza shops are under the lockdown

One in six South Africans works in the informal economy, which provides more than twice the number of paid jobs than the mining sector. More specifically, informal trade in food supports 500,000 livelihoods nationally and accounts for 40% of the economic activity in informal townships. According to Mastercard‘s, Insights into the Informal Economy Report, there are more than 1.5 million informal enterprises generating turnover of around R75 billion a year, paying VAT on their substantial purchases, employing people, and generating incomes for families across the country. Spaza shops and informal food trade outlets are especially important for low-income households because they sell products in small quantities, ‘breaking bulk’ so that it is more affordable to those living in the townships. These families need to buy smaller amounts given their low and inconsistent incomes, and limited storage space.

Under the conditions of the lockdown shops can apply for permits to remain open, but most spaza shops may not have the means to apply. Even those few shops that remain open find that demand falls dramatically since customer footfall outside of schools and bus stops, where they tend to be clustered, will drop to zero. Moreover, shop owners find it difficult to travel to wholesale markets to continue their trade, which causes these suppliers to similarly collapse. For example, an estimated 60% of the goods traded in the Johannesburg Fresh Produce Market sell into the informal township market so these suppliers depend on spaza shop owners to help them move goods.

Although supply and demand conditions for spaza shops has become difficult for many, families in townships depend on these shops for their daily needs. Their dependence on these shops is more acute during the lockdown. Spaza shops are usually within walking distance of consumers’ homes and the combination of high transport costs and restricted movement during the lockdown makes them an essential lifeline for households.

Relief efforts for spaza shops are overly restrictive

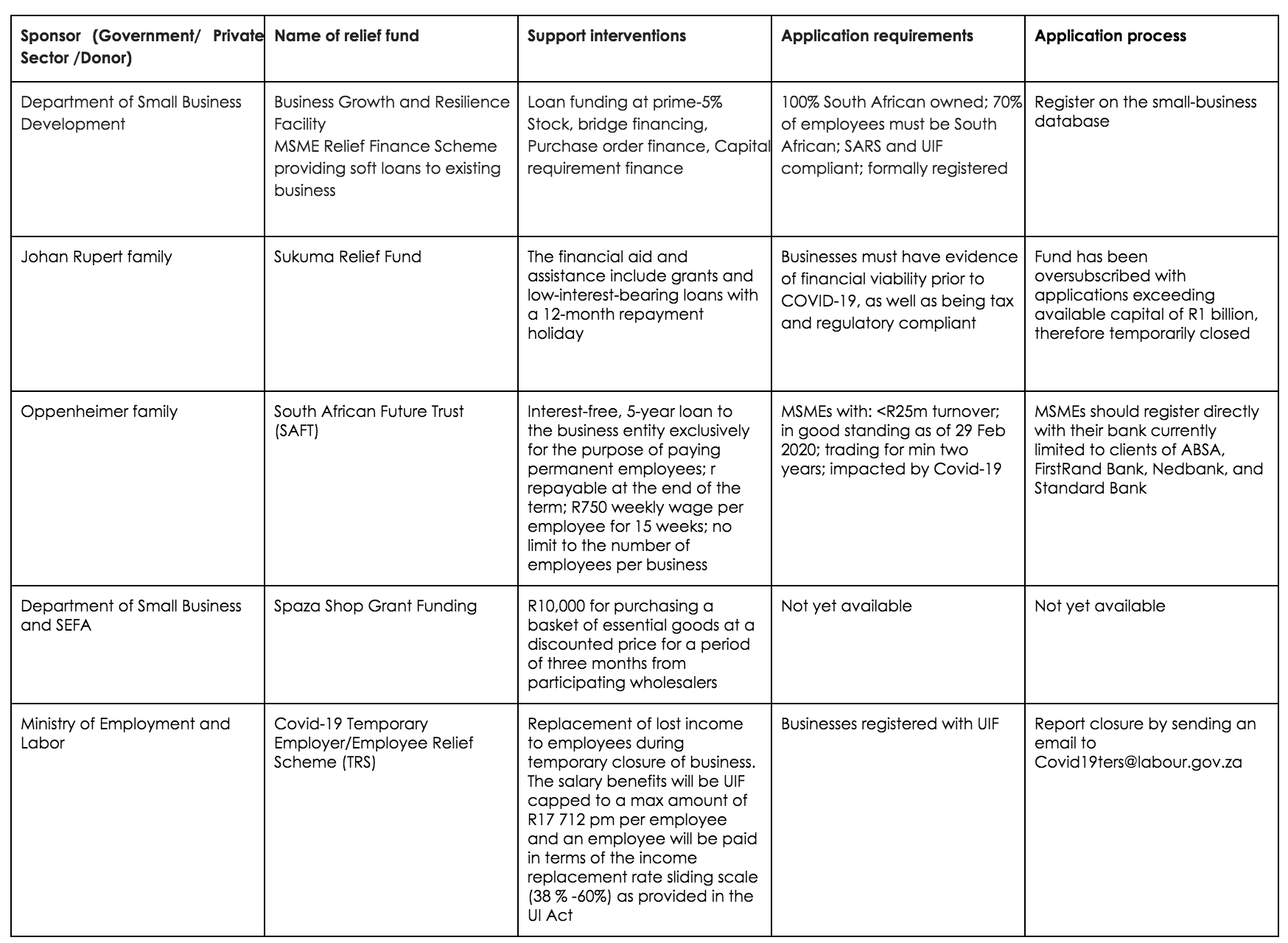

Recognizing the importance of small businesses and their vulnerability, the South African government, the private sector, and philanthropic donors have responded quickly to establish relief funds to alleviate the socio-economic effects of the lockdown and to cushion the impact of the pandemic. However, in all cases, the requirements for these funds act as barriers to entry for most small businesses, especially those that operate in township areas where business is predominantly informal. Spaza shops tend not to be formally registered, may not be tax compliant, and conduct 96% of their transactions in cash, so they may not have financial records. In all, spazas and most micro-enterprises will be unable to demonstrate the impact of COVID-19 on their businesses and will not qualify for these funds.

The table below summarizes the relief initiatives currently available to small businesses in South Africa, and notes their requirements. It is clear that the interventions do not take into account the unique circumstances and limitations of informal businesses:

In addition to not being able to meet the requirements of these funds, spaza owners have the digital tools to register or apply for them. Given the current state of emergency, relief efforts need to extend compassion to those who are unemployed, self-employed, microentrepreneurs, and those doing the best that they can to feed their families. They need to consider the challenges faced by small businesses to attain compliance and implement support mechanisms that enable informal traders and spaza shop owners to survive the economic impact of lockdown, and continue to serve their vulnerable customers.

Opportunity for inclusion

Rather than exclude informal trade, this crisis provides the opportunity to finally break down the measures that exclude such businesses. Physical means of payments – such as cash – have been actively discouraged through the crisis in other markets for their potential of carrying the virus. This is the time for the financial services industry, the payments regulator, and digital payment providers to work together to reduce the barriers limiting the use of digital payments by small businesses in informal markets. This is the time to assess interchange fees and merchant discount rates and together invest in mechanisms that enable spaza shop owners to accept digital payments to access relevant tools to access credit. Merchants without access to digital payments lose out more as remote buying increases, and digital payments continue to enable informal merchants to generate digital financial records.

As revenue for these shops declines, so does their ability to replenish stock in a timely manner, which increases the need for credit lines. There lies an opportunity to collaborate within the retail sector, for fast-moving consumer goods manufacturers to extend credit lines to informal retailers and to support lending startups such as Lulalend, Merchant Capital or Retail Capital so they can lend to small businesses in the township economy. To facilitate this access to credit, we also need innovations that provide alternative credit scoring mechanisms, leveraging the data in cash receipts, purchasing orders, and VAS terminals used by informal merchants.

Once these shops are more – rather than less – connected, they can also serve as critical last-mile distributors and suppliers. They can be leveraged to help social grant beneficiaries to purchase food, purchase airtime, and access healthcare without using cash. With this support, these shops can continue to serve the vulnerable families in the townships, preventing them from having to travel to urban areas for essential goods.