Fintech accelerator programs find new opportunities in adapting to COVID-19

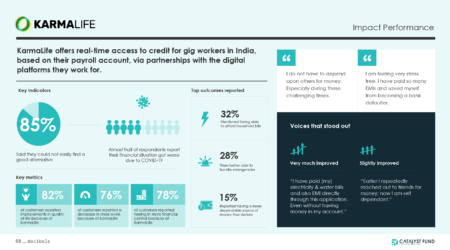

Last year, with the support of JPMorgan Chase & Co, Catalyst Fund started working with Bharat Inclusion Initiative’s (BII) Financial Inclusion Lab, the Financial Health Network’s Financial Solutions Lab, and the Resolution Foundation (RF, UK), to distill best practices and lessons learned for accelerating inclusive fintech startups. The goal has been to understand how acceleration programs and innovation funds like ours can best support impact startups and spur more innovation for underserved populations.

A few weeks ago we shared a detailed paper of our findings, reflecting 10+ collective years of acceleration work (see image below), and last week we convened other leading acceleration stakeholders – including Startup Bootcamp, Village Capital, FCDO, UNCDF, Blue Ridge Labs, and many others – to discuss how the sector is adapting for remote acceleration.

Together, we found that remote acceleration has allowed for greater flexibility and tailoring within our programs as resources and work are delivered directly to startups (instead of in groups). However, establishing trust between partners and within peer networks is a challenge.

Effective acceleration amidst a pandemic

Remote programming has allowed accelerators to bring even more firepower to their programs.

Since conferences, mentorship opportunities, ecosystem events, and entrepreneur networking have all gone online, the pandemic has strengthened and increased adoption of digital tools and infrastructure – much of which will continue to deliver value beyond the eventual return of in-person acceleration.

This turn to digital tools has allowed programs to increase our startups’ access to connections and information. Many programs that earlier relied primarily on in-person networking and mentorship have taken advantage of the remote context to connect ventures from different geographies and cohorts, giving them more support and connections than before. Remote working has also allowed many programs to access more niche support and mentorship for ventures that may have otherwise been unavailable for intensive in-person acceleration.

Furthermore, many accelerators noted that remote events add additional value to the ecosystem since they allow stakeholders to participate even if they’re unable (or unwilling) to travel. Previously, these events were typically hosted in and around tech hubs (e.g., Nairobi, Mumbai) because event attendees, ventures, and investors are geographically concentrated in these areas. However, this concentration ended up excluding those from weaker tech ecosystems (from VilCap blog) who may in fact benefit more from access to such events.

Finally, many of the programs agreed that the increased access to mentors, experts, and events provided by remote acceleration were positive improvements to their programs and have increased the value delivered to their ventures and the ecosystem.

The pandemic has raised new questions about the balance between tailored acceleration and standardized content and tools.

As the pandemic has forced content delivery online, some programs are now able to provide more tailored support, as they are interacting with startups on an individual basis. For example, many of the programs that previously used conferences, bootcamps, and other in-person training or peer-to-peer learning opportunities to address the startups as a group have shifted acceleration work towards 1:1 engagements with individual startups.

In contrast, others have moved to less tailored support with more dependence on repeatable, widely-distributable online content. Some programs traditionally focused on tailored support are using online programming to standardize more of their offerings, as this provides an easy and cost-effective method to increase the cohort size and geographic reach of the program (from VilCap blog). This can be a positive change in these programs because it provides increased access to content for founders from industries or regions that may not have been traditional focus areas.

It is not yet clear what the right blend will be between customization and accessibility. Our paper on accelerator effectiveness found that a tailored offering was one of the most important program components when it comes to delivering value to the venture itself. However, the financial sustainability and increased scale of our programs are key challenges that can be addressed in part by moving to more digital tools and content. There will need to be a balance between increasing access and lowering the cost of our programs while maintaining the parts of the offering that deliver greater value and help companies to grow and succeed.

Being conscious of CEOs’ time has become more important than ever but requires deliberate modifications to our programs.

Our portfolio companies have had to pivot to find new opportunities within the new normal of the pandemic. Startup leaders have also faced increased personal stresses, from homeschooling, to sickness, and an inability to socialize. Although remote acceleration allows programs to direct materials and engagement to others on the startup team, the CEO is often the key contact person and gatekeeper to the rest of the team. This can mean an additional layer of effort on his/her part.

Some CEOs appreciate those programs that have moved their content to pre-recorded, online materials, because it allows them to complete the modules within their own schedules and time constraints (from VilCap blog). This increased flexibility can be critical for founders navigating unprecedented personal and professional challenges.

However, remoteness has made programs even more reliant on the founders for success. When on-site acceleration was possible, the accelerator program could connect with other members of the executive or operating teams to learn about the venture and complete modules of the acceleration. In the remote context, the CEO has to deliberately include other members of the team and delegate, which can be difficult in practice.

All programs mentioned Zoom fatigue as a critical challenge to remote acceleration, and we debated how to complete acceleration remotely without simply moving every hour of interaction to online meetings and lectures. Staying focused and engaged in Zoom meetings for more than one or two hours is a challenge for workshops and storyboarding, which are often key tools used in the venture building process and tend to require longer periods of concentration to complete. Many programs have adapted by deliberately designing and breaking online content into smaller, shorter pieces.

Finally, the inability to travel has increased the need for documentation in the form of decks, models, etc. from both the venture and acceleration teams. Effectively, founders are completing additional “homework” to build this documentation, and often, it’s only for the purposes of the programs. Many felt that the increased reliance on documentation and inability to complete longer blocks of in-person work have slowed the cadence of the programs and the acceleration process.

Trust, relationship-building, and organic interactions are cross-cutting themes that are important to all aspects of effective acceleration – sourcing, support, and ecosystem building – and have fundamentally changed in a remote context.

Sourcing and due diligence rely heavily on in-person meetings, field visits, and “gut feelings” about the founders and the venture. For example the Financial Inclusion Lab relies on a series of in-person events as part of its sourcing process. Effectively sourcing and completing remote due diligence has become a common topic of discussion among investors and accelerators and remains a key challenge for our programs, ventures, and investors.

All of the accelerators have noted that trust and transparency are fundamental to the venture support process, and that trust has become harder and takes longer to build in a remote context. All accelerators provide peer-to-peer learning as a key element of the program, and for some, like Village Capital, it is core to the value proposition and operation of the program.

There was mixed feedback about how peer-to-peer learning has changed in a remote context. Without the constraints of physical meetings, many programs have adapted their peer interactions to span geographic cohorts of ventures, eliminated geographic focus or requirements, and have opened alumni ventures to events with the new cohorts. This has provided founders with a larger network from which to learn. However, many programs note that in-person, informal interactions are critical to building strong and meaningful relationships between peers – so the increased breadth of interactions has come at the cost of depth.

Many also expressed concern over the loss of organic, spontaneous interactions that catalyze new ideas, partnerships, and friendships. These meetings are one of the core pillars of how innovation is sparked, and is a foundation for the idea of maker spaces, incubators, and ecosystem events. These meetings have been dramatically reduced in our programs and in the context of the pandemic and could have lasting negative consequences for innovation as we begin to recover from the pandemic.

Questions about the potential for biases and the impact of remote acceleration on the inclusivity of our programs were discussed, and remain to be answered.

As a part of the discussion, a debate opened about the impact of remote acceleration on inclusivity and potential biases. Remote acceleration replaces spontaneous and in-person relationship-building with deliberately-crafted opportunities for interactions like demo days, panels, and online forums. It’s possible that the move to more formal interactions could improve the visibility of female and local founders to get exposure, funding, and support. Remote acceleration may also allow those who still have a day job while working on their startup or are managing household responsibilities (from VilCap blog) to still participate in acceleration. Unfortunately, initial evidence shows that the pandemic has concentrated funding even more among male founders, as VC funding for female founders is at a three-year low.

Remote due diligence and sourcing may also be favoring startups that are tech-based, rather than models with significant field operations. Models with higher-touch components with agents or users may feel risky to selectors/investors, especially without the ability to observe them firsthand.

Many of the programs present took this discussion as a call to action to actively include inclusivity-focused efforts in our work, including incorporating inclusivity into selection metrics, having a diverse internal team, and using targeted recruitment to source diverse startups. As we navigate the difficulties imposed on us by the pandemic, we should prioritize an effort to limit biases and discrimination in our programs.

The world has dramatically changed since the onset of the pandemic, taking lives and shaking economies at their core. Millions of people have lost their jobs, businesses have had to shut down, many families were pushed into poverty, and existing inequalities have widened. And yet, we have seen many startups respond quickly with innovative solutions, from extending credit to small businesses at better terms, to enabling cash transfers and access to essential goods, to putting medical supplies and tests in the hands of communities. As a community, we continue to adapt and seek new ways to better support these ventures in reaching scale and creating a more equitable recovery from the pandemic.