How domestic fintech ecosystems shape the nature of innovation

Blog 1 of the Recovtech series, this post written in partnership with members of the South Africa Recovtech team.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic brought widespread economic distress, many nations had been wrestling with how to increase their rates of inclusive economic growth — that is, growth which benefits the bottom strata of society. The three largest African economies — Egypt, Nigeria and South Africa — are no exception: they have all experienced generally low, even sometimes negative, per capita growth in income over most of the last five years. Even Kenya, a country which has reported higher per capita growth rates than the others, has seen relatively stagnant employment growth (One measure is that the proportion of salary and waged jobs to total employment has changed little in a 5 year period to 2018 in the World Bank Jobs Database). There are many barriers to faster inclusive growth in a country; we focus here on how fintech innovation can help achieve this increasingly vital policy objective.

This blog is the first in the Recovtech project series which is engaging policy makers and private sector innovators in these four leading African economies on how best to promote domestic ecosystems for fintech, which support inclusive growth in COVID-19 recovery. Together, these four countries contain around one third of Africa’s population, but contribute closer to half (44%) of the continent’s economic activity (measured by nominal GDP 2019). Fintech innovations which originated in these countries have already diffused and affected the rest of the continent.

Digital payments companies have traditionally led fintech innovation globally

During the past decade, some fintech companies have become global household names. The biggest ones have, not surprisingly, grown out of the two largest national fintech ecosystems: the US and China. PayPal, founded in Silicon Valley back in 1998, now has over 300 million customers and was recently valued at over $200 billion, more than all but the biggest global banks. China’s Ant Group was started later, in 2014, although its main product Alipay dates back to 2004. It boasts 711 million monthly active customers and was valued even higher (over $300 billion) in its IPO in late 2020. Both of these companies started with close links to digital commerce, and still have digital payments at their core, but they have also expanded to other financial service offerings, including credit for small merchants — some $10 billion in the case of Paypal, and over $300 billion in the case of Ant affiliate MYBank.

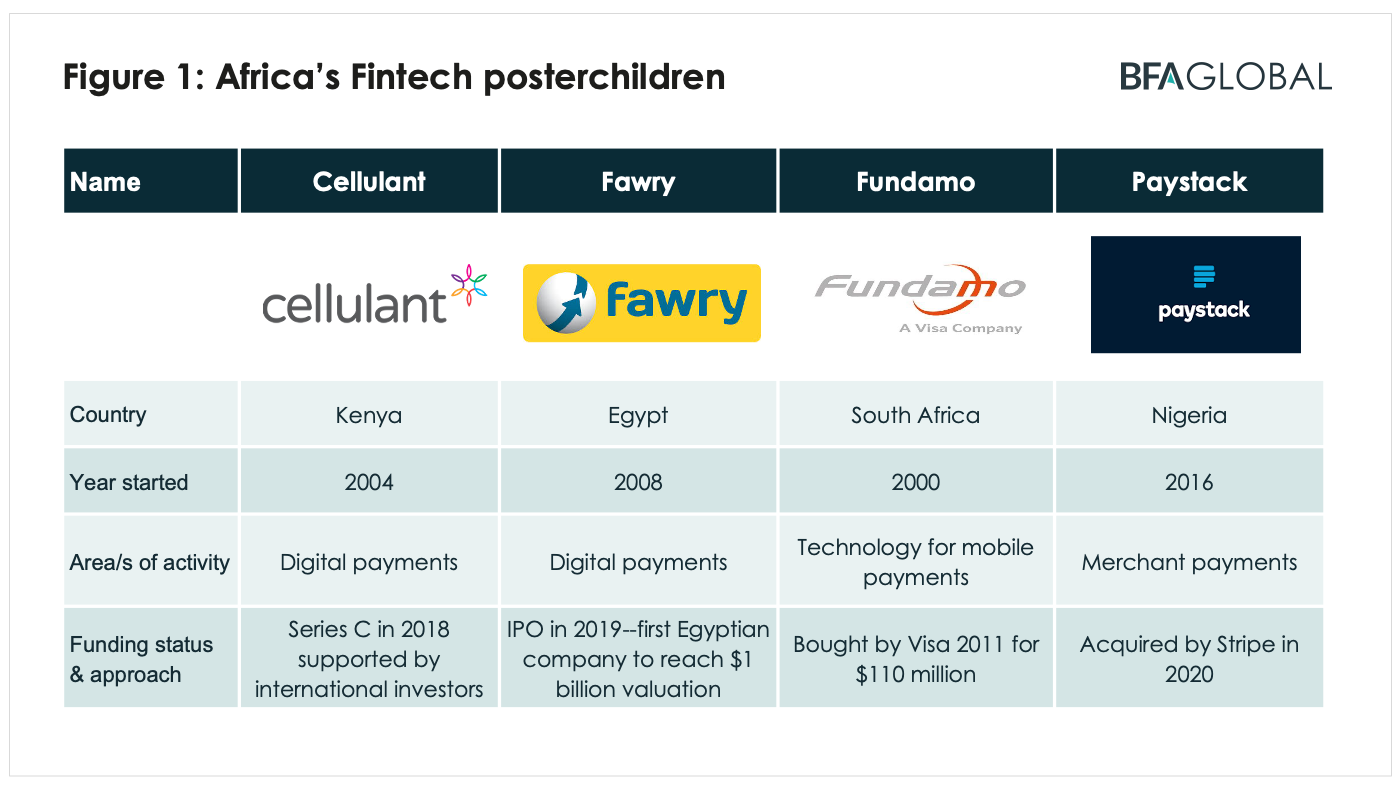

Like these global-scale fintechs, the ‘poster children’ of fintech innovation in each of the four leading African fintech ecosystems so far have also mainly been digital payment companies. This is not surprising. Because regulations were less onerous or less well defined, tech companies have found it easiest to enter digital payments, either working with incumbents or disrupting them. The digital payment sector also has lower financial barriers to entry: it requires less capital than fintech lending or becoming a digital bank, for example.

The table below lists one leading fintech company from each of the four markets. The oldest on the table, South Africa’s mobile payment systems provider Fundamo, was bought out by Visa in 2011 for $110 million. The youngest, Paystack of Nigeria, was most recently acquired by Stripe, another global fintech unicorn which has transformed the world of online merchant acquisition. Fawry of Egypt had its IPO in 2019, 11 years after it started operations, and is today one of the most valuable companies on the Cairo bourse with a valuation of over US$1 billion.

These fintech ‘poster children’ are products of their ecosystems. The digital payments sector has been the most active fintech sub-sector in these countries so far, measured by the volume of fundraising and by the number of startups. However, this may change in the future, as successful firms evolve into other sub-sectors, as Paypal and Ant Group have, and as domestic fintech ecosystems evolve. Indeed, part of the aim of this project is to understand how local ecosystems may evolve so as to produce innovations which are relevant for domestic priorities.

Recovtech scenario seminar 1: South Africa’s fintech innovation ecosystem

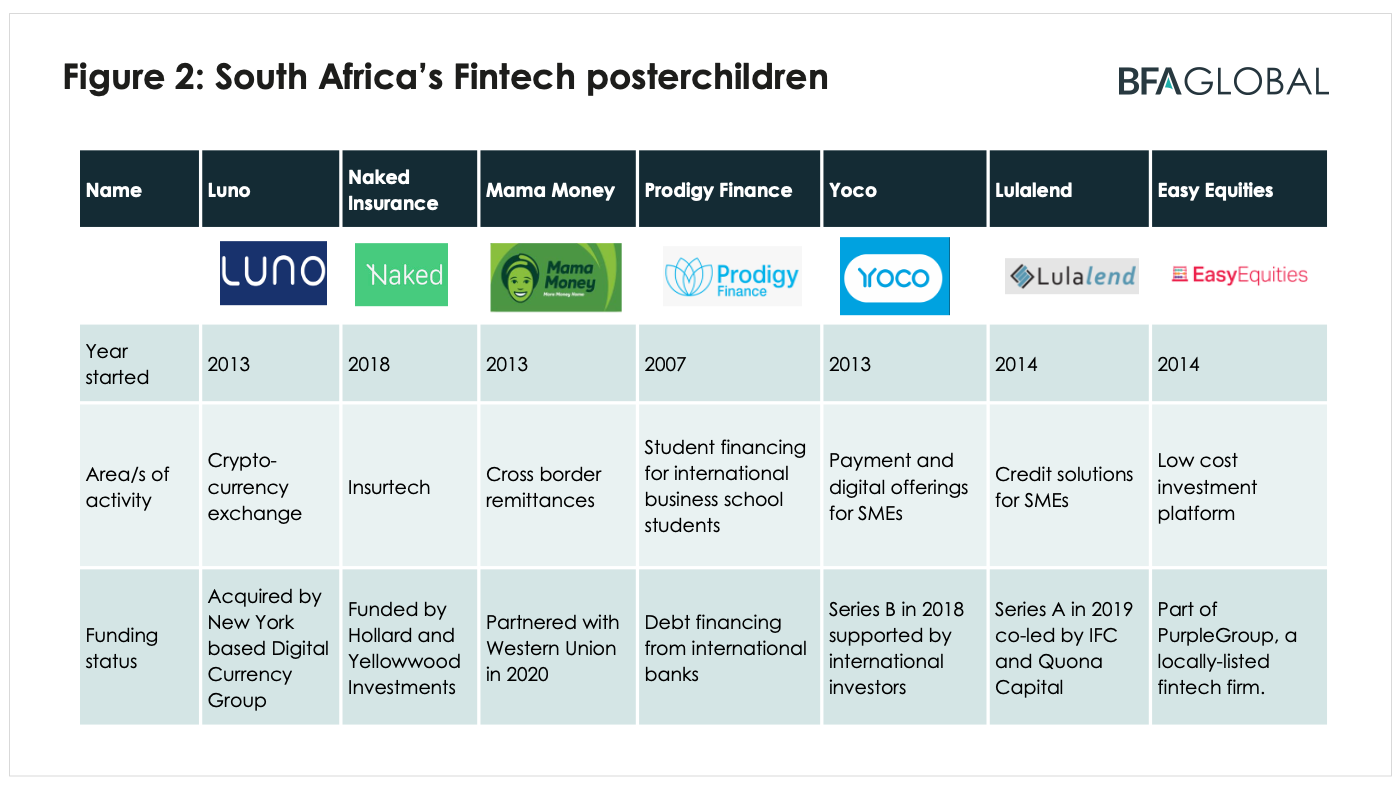

The first scenario seminar with public and private participants from South Africa exposed the variety of “fintech poster children” in the SA ecosystem that have local talent, have raised capital and are providing innovative fintech solutions beyond payments. The table below lists the poster children: Yoco and Lulalend for tailoring solutions for SMEs; Mama Money, for reducing the cost of cross border remittances; Naked Insurance, for deploying tech to create customer value in the insurance space; Easy Equities for creating access and inclusion around investments; Prodigy Finance and TaxTim for innovative solutions in different sectors; and Luno, for the successful exit to Digital currency group. Stash, although a very early stage company, was mentioned for its promising role in mobilizing savings in underserved markets, enabling customers to save as little as $0.30 (R5).

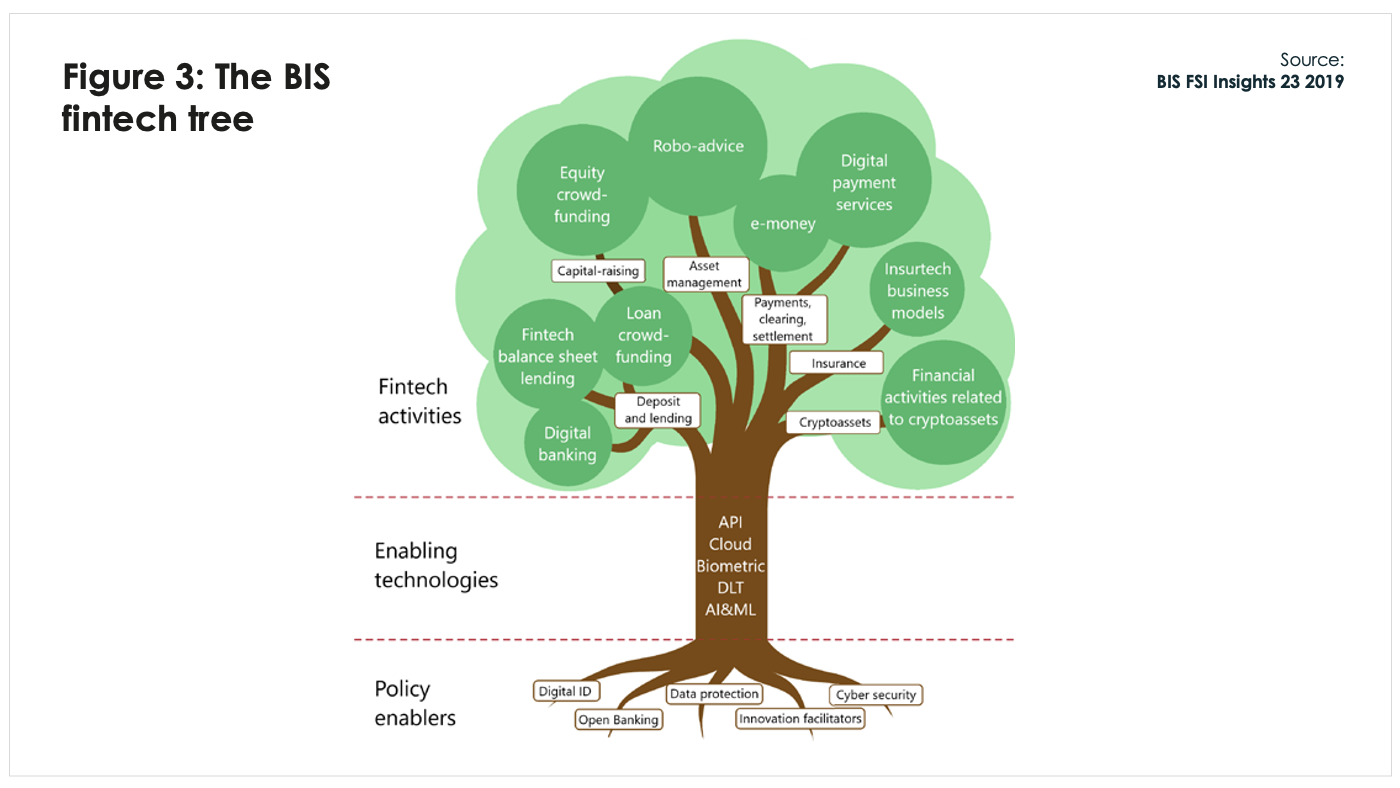

In order to situate these poster children with their respective contexts, we borrow the “fintech tree” metaphor developed by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), shown in Figure 3 below, which defines the fintech phenomenon as a whole along three dimensions: activities (the branches), enabling technologies (the trunk) and policy enablers (the roots).

The metaphor of a tree is apposite for a discussion of fintech ecosystems, since the word ecosystem in this context is originally drawn from biology. It conveys the sense that from strong roots and a larger trunk, more branches are likely to grow, which may produce good fruit. Using the image of tree branches, the BIS picture also creates a taxonomy of the main subsegments of fintech innovation today — alongside payments are digital banking, fintech lending, crowdfunding, robo advising, cryptoasset financing and insurtech. Note that we refer to innovations across all those sub-sectors as ‘fintech innovations’, regardless of the promoter’s institutional form (i.e., whether a startup or established non-bank company or a regulated incumbent).

Fintech innovations are happening in all these ‘branches’ today, in different ways and at different speeds. But not all innovations will have the same potential to contribute towards achieving national economic priorities during the next five years of post-COVID recovery. Domestic ecosystems have a strong influence on the species of trees most likely to survive and thrive. Some of the conditions shaping ecosystems are beyond the power of any individual layers to change, while others result from choices made by financial policy makers and regulators. Through careful choices, policy makers and regulators may be able to cultivate domestic ecosystems which are most likely to create new champions in priority areas.

In the next blog in this Recovtech series, we develop further the metaphor of trees and ecosystems to investigate the distinctive characteristics which shape the nature, pace and type of fintech innovations in domestic markets. The aim of the project is to clarify choices and priorities around ecosystems most likely to bear good fruit in the next season of fintech innovation. If in 2025 we were to list the poster children of Africa’s fintech space again, it seems likely that there will be fruit on other branches of the fintech tree.