Fintech forests: classifying and comparing fintech ecosystems

Blog 2 of the Recovtech series, this post written in partnership with members of the South Africa Recovtech team.

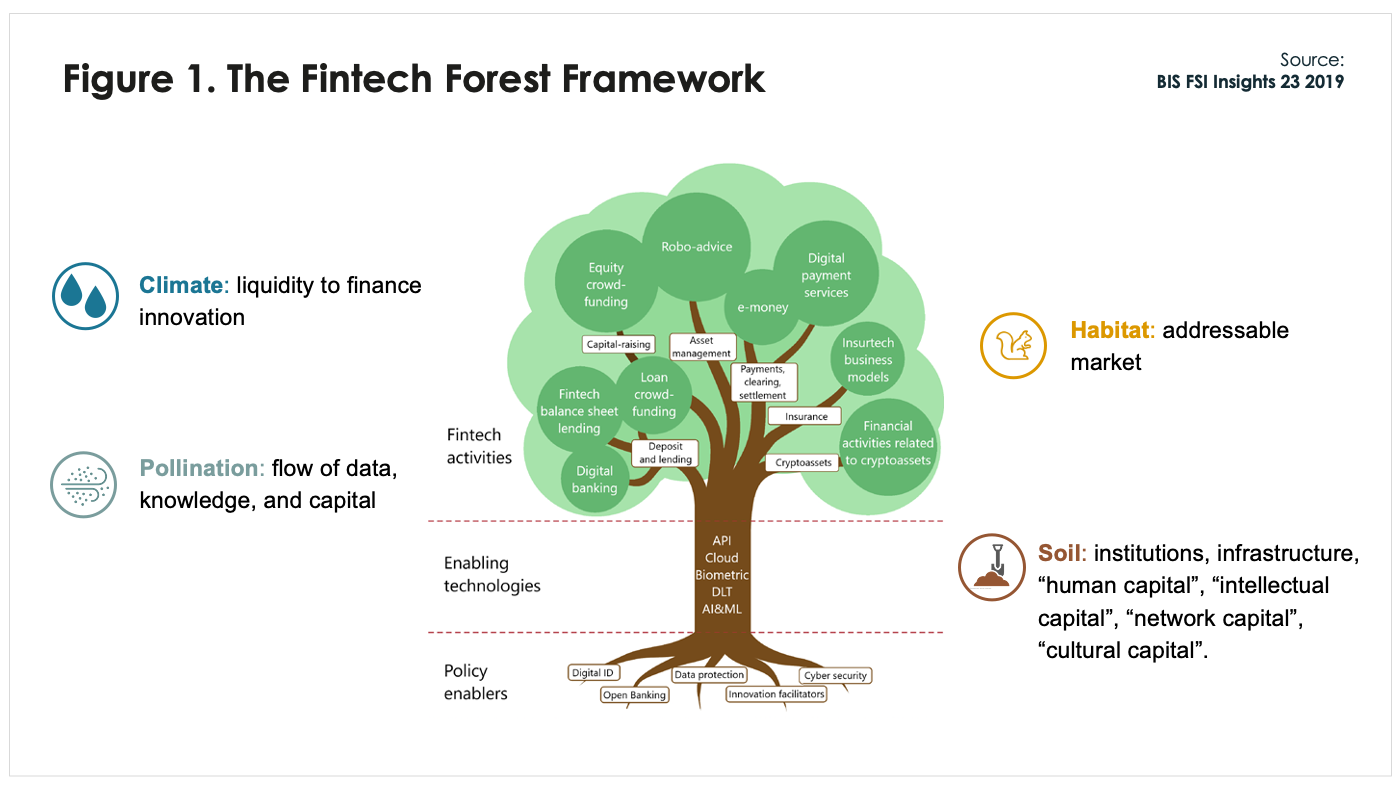

As argued in the first blog in our Recovtech series, fintech ‘trees’ can serve as a useful heuristic for conceptualizing the fintech space in general terms. However, the metaphor omits key environmental factors that shape the wider fintech ecosystem, including institutions, various forms of capital (e.g., financial, human, infrastructure, etc.), and actors (e.g., investors, entrepreneurs, etc.).

To capture these elements, we extend the BIS metaphor to develop a “fintech forest” framework. This provides a basis for classifying and comparing different fintech ecosystems, and by extension, for determining which “species” of fintech trees emerge and thrive in a given market. The point is not simply to draw a pretty picture of distinct fintech landscapes. Rather, the framework will help us understand how the forces and uncertainties unleashed by the COVID-19 pandemic will play out in different contexts. That, in turn, will allow us to identify areas and avenues for restarting inclusive growth using fintech innovation in the short to medium term. First we need to unpack the forest concept, starting from the ground up.

Elements of the fintech forest

- The soil encompasses the myriad factors that help fintech startups take root and flourish into viable businesses. The precise mix of ingredients that together make an environment “enabling” for innovation and growth vary from country to country, but they typically include some blend of institutions and governance (political, legal, etc.); human, intellectual, and financial capital (i.e., ideas, talent, and funding); physical capital (e.g., information and telecommunications infrastructure); and sound macroeconomic fundamentals.

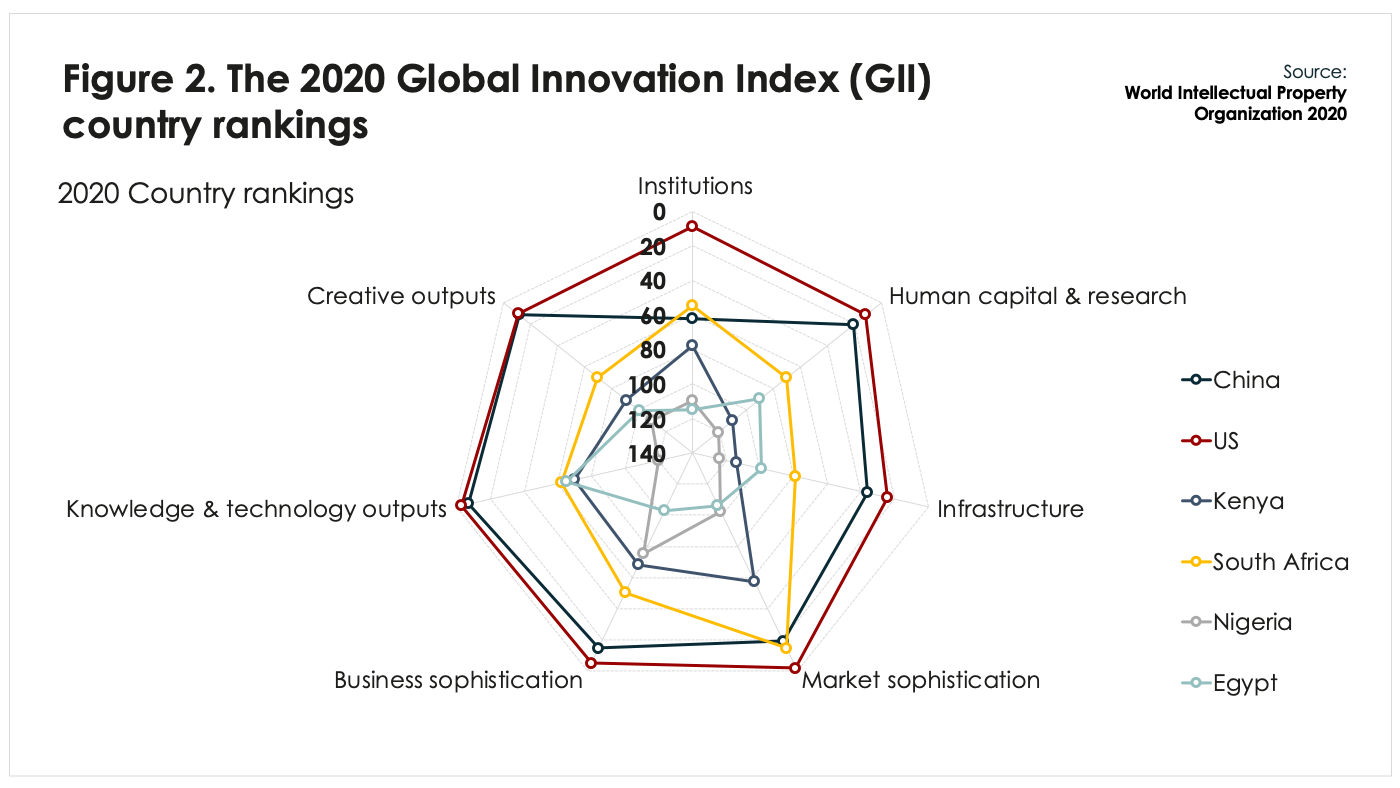

For instance, the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) publishes an annual Global Innovation Index (GII) that incorporates 80 different indicators across each of these dimensions (see Figure 2); we have plotted our Recovtech markets alongside the US and China for illustration. Then there are the harder-to-quantify factors, such as “social capital” or “network capital,” which provide the secret sauce that converts inert institutional or physical capital into dynamic innovation and entrepreneurship.

- The roots constitute the main interface between fintech companies and their environments. Here we find fintech-specific regulation and policy enablers, which include initiatives such as innovation facilitators and regulatory sandboxes. Both need to be suited to the soil in order to serve as good anchors for the tree. Merely adopting standards or best practices for “enabling” rules or policies rarely suffices to stimulate innovation, much as transplanting a tree to foreign soil does not guarantee that the roots will take hold.

A successful regulation sandbox, for instance, presupposes there is sufficient trust and connectivity (i.e., social and network capital) between regulators and policymakers to make the collaboration fruitful. Likewise, the relative stringency or permissiveness of regulation often matters less than the quality and predictability of the regime, as we illustrate through the example of P2P lending in China in blog five of this series.

- Trunks equate to ‘enabling technologies’ — literally the pillars underpinning fintech firms’ business models. The BIS lists five core technologies: application programming interfaces (APIs), artificial intelligence (AI), biometrics, cloud computing, distributed ledger technology (DLT), and machine learning (ML). To this we might add the Internet of Things (IoT) and mobile phone/internet connectivity.

The analogy works as follows: the stronger the trunk, the broader and more sophisticated the range of fintech activities it can undertake (the ‘branches’), the larger canopy of products and services (the “fruits and leaves”) it can conceivably offer its customers (the “habitat”). It follows that denser forests and/or bigger trees provide greater choice and variety of financial offerings. On the flip side, the bigger the addressable market, the greater the growth potential from reaping returns to scale and network effects. Hence, the size of the “habitat” also matters. It is perhaps no coincidence that the biggest BigTechs all hail from the largest markets.

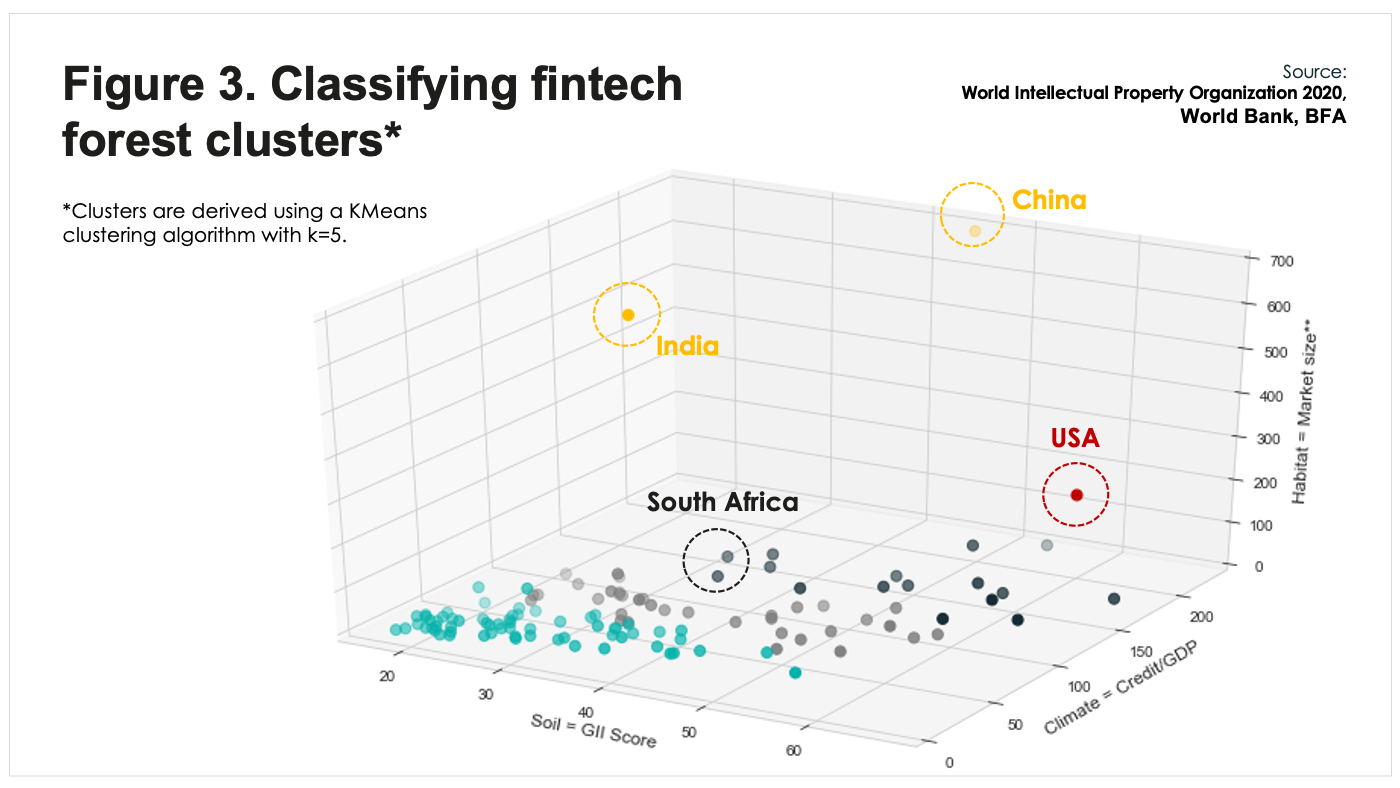

- Water has an obvious parallel as liquidity in this analogy. A climate of stable, plentiful, and predictable funding is correlated with larger fintech ecosystems, as shown in Figure 3 below. The level and concentration of financial capital accumulation may also determine resilience to financial shocks such as the pandemic. Firms that can draw on large internal pools of capital (groundwater?), notably the BigTechs with their massive war chests of cash reserves, are far more likely to withstand funding droughts than smaller players who rely on flighty external funding. That said, fintech businesses that arose out of conditions of scarcity may also be more adept at harnessing and conserving liquidity than their peers in more “humid” climates.

- Finally, pollination is a fitting metaphor for the propagation of fintech and the growth of ecosystems. Just as trees disperse seeds and use pollinators for reproduction, so fintech ecosystems depend on the ability of entrepreneurs and innovators to disseminate data, knowledge and ideas and convert them into startups — in other words, on the openness of the ecosystem. Whether they ultimately sprout into startups depends on the other environmental factors, not least the regulatory barriers to entry.

Of course, “cross-pollination” of ideas is not the only way innovation happens; much “self-pollinating” innovation occurs within organizations, be it through “intrapreneurs” or conventional research and development. We will examine the interplay of openness and innovation in the next blog of this series.

Archetypical fintech forests: Redwood and Banyan ecosystems

Using proxy measures of soil quality, climate conditions, and habitat size, and plotting countries along these dimensions on a scatter chart in Figure 3, we can discern several clusters of ecosystems. Two groupings immediately stand out: the US for its high score in the GII innovation index; and China and India for their large market sizes. In accordance with our fintech forest analogy, we label these groupings “Redwood” and “Banyan” ecosystems for the emblematic fintech players that they have given rise to, which we examine in turn before exploring other ecosystem types.

The analogy of Redwood trees, the largest in the world, nicely describes the prodigious scale and maturity of Silicon Valley’s BigTech poster children Amazon, Google, Microsoft, and their peers. Although not strictly fintech companies, their computing platforms (AWS, Google Cloud, and Azure respectively) form the backbone of a relatively open technology and data infrastructure that underpins much of the US fintech industry, including its largest players (e.g., PayPal relying on Google Cloud and Stripe on AWS). By offering affordable, scalable and accessible cloud computing, AI/ML capabilities, and API marketplaces, the redwood BigTechs have enabled open innovation throughout the ecosystem.

Aside from aiding other ecosystem players, BigTechs are gradually rolling out a suite of financial services directly to their users – for instance, Google Pay in payments or Amazon Lending in credit. Their ability to embed financial services into ubiquitous technology offerings has the potential to boost financial inclusion and digital transformation in the US and further afield. Their dominant position in cloud computing, coupled with a global reach and entrenched customer base, is likely to make them a formidable competitive force in the fintech ecosystems worldwide, provided they can secure market access.

Many tech hubs harbor ambitions of cultivating their own Redwood forests, as suggested by the proliferation of “silicon” monikers over the past decade suggests (e.g., silicon roundabout, silicon savanna, etc.). However, the environmental factors that gave rise to Redwood fintech companies are complex, historically contingent and predicated on lengthy processes of capital accumulation. A “rich” soil foundation, together with open innovation and ample venture capital, allowed the redwood ecosystem to grow more or less organically with minimal state intervention or planning (although, as Mariana Mazzucato points out, an entrepreneurial state did play a prominent role as early-stage venture capitalist). Market-driven open standards around data sharing, data protection, and cybersecurity preempted the need for prescriptive regulation during their fintech’s formative years, while vibrant startup scenes obviated the need for “innovation facilitators.”

Framed in terms of our analogy: just as Redwood trees have surprisingly shallow roots given their stature, so arguably do their fintech analogs require few policy enablers to grow and propagate. But this also makes them harder to transplant.

That said, taking a Redwood route to ecosystem cultivation may not be feasible nor advisable in other contexts. While clearly effective engines of innovation and inclusion, Redwood ecosystems also have inherent weaknesses and risks. Their openness is grounded in reservoirs of network and social capital, which can be depleted if data, privacy and customers are not adequately protected. Failures of self-regulation can lead to unseen build-ups of risk along the lines seen during the global financial crisis with mortgage-backed securities. Add to that the concentration risk inherent in a handful of BigTech platforms furnishing most of the enabling technology infrastructure. This market dominance is raising concerns about data sovereignty and competition, which will only increase as they enter financial services in earnest.

Similar concerns about data sovereignty, competition and consumer protection surround Banyan ecosystems–the term we use to describe the sprawling “super-platforms” found in China and, to a lesser extent, India. Their tangled trunks are an apt metaphor for the complex “ecosystems within ecosystems” that are the Chinese tech poster children of Ant Financial and Tencent. While these lack the cloud prowess of their US counterparts, at least in terms of market share, they excel at API-based transactional platforms and state-of-the-art biometrics and AI. Their super-platforms incorporate diverse sectors ranging from e-commerce to mobile payments and social media.

Banyan BigTechs are capable of supporting vast populations of users in a largely self-contained habitat, harvesting customers, data and liquidity from within rather than relying on the wider ecosystem or environment. This allows them to internalize the rewards of network and scale economies and pass on the savings to users. To illustrate this point: the Alipay (Ant) and WeChatpay (Tencent) payment systems remain non-interoperable, while their respective credit scoring arms — Tencent Credit and Sesame Credit — have refused to share their customers’ data amongst themselves or the rest of the fintech ecosystem. It is in this sense that we consider Banyan ecosystems as “self-pollinating” and relatively closed, as opposed to the “cross-pollinating” Redwood ecosystems.

That is not to imply that Banyan forests are less capable at generating innovation and growth. The dramatic rise of Chinese fintech over the past decades and the accompanying gains in financial inclusion testify to the contrary. Thanks to outsized network effects, Banyan ecosystems may be more effective in harnessing scarce resources and lowering costs for consumers compared to Redwood ecosystems, which in turn makes them better at surviving and servicing less forgiving climates. However, self-pollination is arguably less prolific and diverse than cross-pollination, which relies on innovators and entrepreneurs (“pollinators”) to disseminate new ideas and convert them into new businesses. The result is that Banyan forests are sparser than Redwoods, admitting fewer competitors and potentially limiting choices for consumers.

As with Redwoods, Banyan ecosystems grow out of conditions that are not easily reproduced in other environments. Chief among them are huge populations of users, which put India and China in a class of their own. The other factors are more unique to China: a sustained and concerted effort by successive Chinese governments over the past couple of decades to strengthen the foundations for innovation and boost venture capital funding. This is a feat akin to geo-engineering that other governments will struggle to repeat. Again, it is not clear that they should aspire to do so. Policy interventions of this scale throw up their own sets of problems, such as the misallocation of resources and stifling of organic competition, examples of which can be seen in the Chinese “internet finance” bubble covered in blog five of this series. The prominent role of policy enablers and state direction in the ecosystem is illustrated by the aerial prop root system of Banyan trees, where the roots and trunks are inextricably intertwined and mutually reinforcing.

South Africa’s savannah forest ecosystem

Sitting somewhere between these two extremes, the South African fintech ecosystem might be best described as a savannah forest ecosystem (some participants indicated that a pine forest would be a better description, but ultimately savannah prevailed). It is sparser than Redwood forest ecosystems, but more populous than Banyans. Judging from the country’s ranking in the WIPO GII (see Figure 2), soil is less fertile than either, but still bountiful, as is evident from the vibrant startup scene.

South Africa boasts many fintech success stories such as Fundamo, Luno, and MamaMoney. Still, like the acacia trees that dot the savanna, South African fintech companies stand out for their large canopy of products and services, supported by a relatively narrow technology base compared to Redwoods and Banyans, particularly in cloud computing (although this is changing, as Microsoft opened its first data centers in March 2019 and AWS followed suit in April 2020). This top-heavy structure partly reflects physical infrastructure and human capital gaps.

To compensate, South African authorities have fortified roots through a host of public policies that enable the provision of digital services, including a framework for digital ID used in financial services, a national framework for data protection, and a cybersecurity framework. A pioneering Intergovernmental Fintech Working Group (IGWG) has set up a regulatory guidance unit, a regulatory sandbox, and an innovation accelerator. Even so, there is broad agreement among ecosystem stakeholders that a greater degree of coordination and dialogue between the public and private sectors is required in order to spur innovation.

The purpose of examining South Africa’s and other fintech ecosystems through this lens is to help us understand how the forces and uncertainties wrought by the pandemic will play out in the near term. It should also allow us to evaluate the degrees of freedom for ecosystem stakeholders to shape outcomes, in particular, with a view towards restarting inclusive growth. We dive into these topics in our next blog.