Inclusive fintech lending–Lessons from US and China

Blog 5 of the Recovtech series, this post written in partnership with members of the South Africa Recovtech team.

In blog 4 of this Recovtech series, we made the case for financing MSMEs in order to aid post-COVID-19 economic recovery. Fintech lending is an emerging category that addresses this need. For the legions of MSMEs in Africa facing prolonged demand destruction, supply disruptions and funding freezes, fintech lending promises both a lifeline and an engine for powering inclusive and sustainable post-pandemic recovery. But can fintech lending live up to this promise and address the pressing needs of the MSME sector?

In this blog, we look to lessons from China and the US, by far the largest “alternative credit” markets in the world. In these countries, fintech lending has become an increasingly important source of MSME financing. After more than a decade of activity, these markets also provide enough evidence to support the claim that fintech lending can meaningfully advance financial inclusion at scale. They provide lessons for other countries on the journey about the risks and potential setbacks, including serious lapses on the part of both fintech firms and their regulators.

The COVID pandemic has also administered a sharp shock that has tested the resilience of emerging fintech business models. The US and China enjoyed special conditions as first movers, which enabled them to develop and test new lending approaches that are now spreading to other markets. The diffusion of fintech lending models makes lessons from the US and China increasingly relevant in other markets.

A taxonomy and brief history of fintech lending

Fintech lending refers to new, technology-enabled business models related to deposit taking, credit intermediation and capital-raising. The new technologies in this case are mainly digital distribution, robotic process automation and algorithmic credit scoring based on machine learning and big data mining. Together, these technologies promise to improve the accuracy of credit underwriting and to automate key aspects of the loan life cycle, from customer onboarding to loan servicing, in ways that transform the unit economics in small-value, low-margin market segments, like MSME lending.

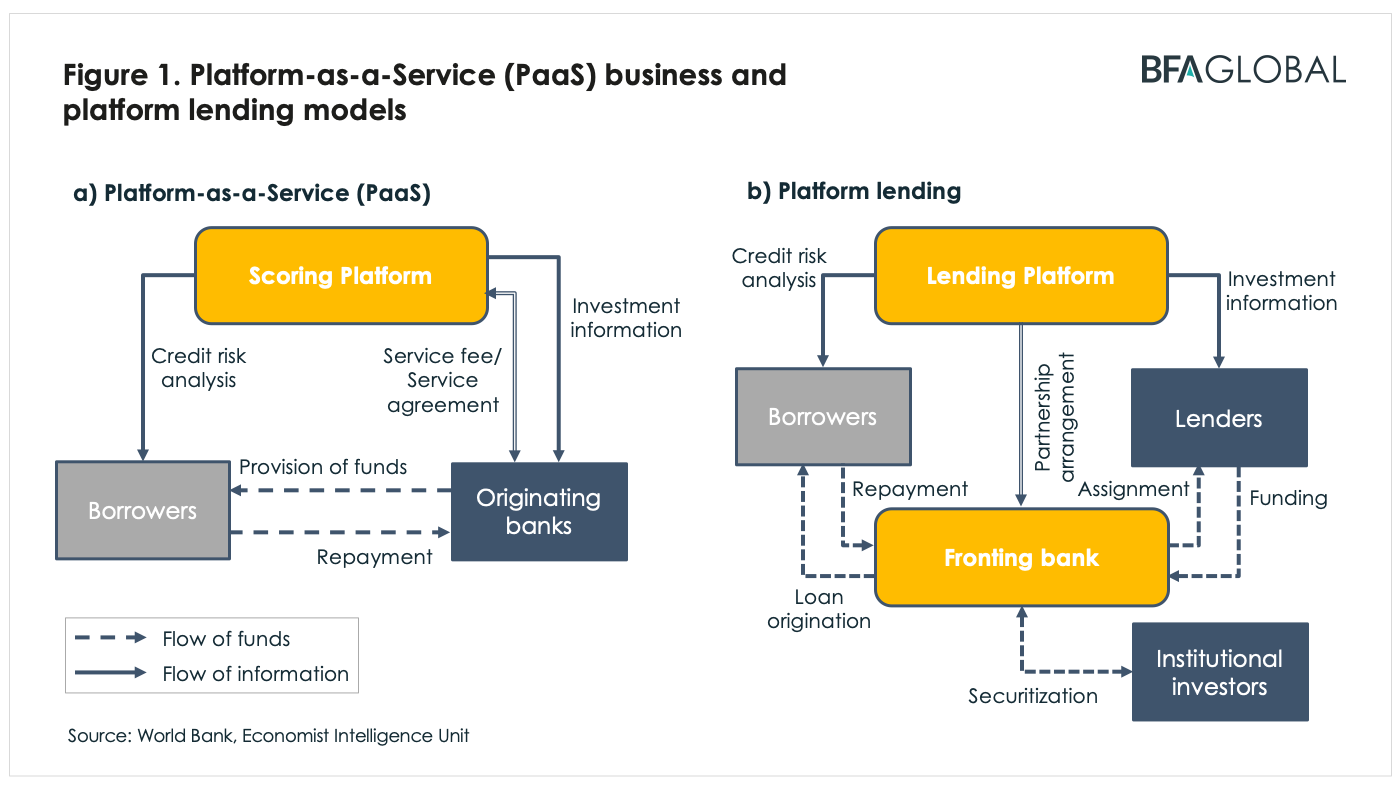

Fintech lenders take on a variety of forms, depending on the market structure and regulatory environments they operate in, and they span the entirety of the retail lending value chain. A 2020 FSI paper on fintech lending categorizes the main types that have emerged:

- Platform lenders act as intermediaries between loan applicants and creditors, whether individuals (“person-to-person, P2P”) or institutional investors (i.e., “marketplace lending”), by providing matching services.

- Balance sheet lenders directly originate and book loans using debt or equity financing, or customer deposits where they can obtain banking licenses.

- Some fintech platforms provide credit scoring and matching services to originating banks as a Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS), either white labeled or co-branded. In these cases they do not assume any credit risk.

- Finally, ecosystem lenders harvest data from their existing customers, such as merchants on e-commerce platforms or users of e-payments platforms, and use this with or without partner lenders to extend credit to these customers, directly or indirectly. This latter category is largely the preserve of so-called BigTechs, the technology giants such as Alibaba or Amazon, who operate large platforms that bundle together various financial and technology services, including social media and cloud computing.

Fintech lending took off in earnest in the US and China around 2010, as “alternative” lenders stepped in to fill the void left by banks that had pulled back on lending to small and subprime borrowers following the Global Financial Crisis. Most platforms started out as P2P lenders and expanded into business lending, attracting institutional funds in the US in particular. Business lending accounted for roughly one third of the $305 billion in alternative lending worldwide in 2018, according to estimates by the Cambridge Center for Alternative Finance (CCAF). China’s proportion was in line with the global average while it was lower in the US, where personal lines have played a larger role.

The US fintech business lending market today is dominated by three BigTech lenders — Paypal Working Capital, Amazon Lending, and Square Capital — and two hybrid platform/Platform-as-a-Service (Paas) players — Kabbage and OnDeck. There are also a number of smaller marketplace lenders, such as Credibly and BlueVine. Although competition has intensified in recent years, SME-oriented fintech lending has continued to attract startups and interest from venture capital — at least until the pandemic hit.

In China, after some years of rapid growth during which lending platforms provided billions of dollars of funding for small businesses, the industry experienced a major shake-out, starting in 2016. A string of high-profile frauds and failures eroded trust in fintech lenders and eventually led financial regulators to crack down on them. By the end of 2019, the number of P2P lenders had fallen from over 6,000 at the peak to a mere 343. That decline left the field wide open for BigTech ecosystem players such as Ant Financial’s MYbank and Tencent’s WeBank, both regulated banks, to pick up the slack. MYbank grew its SME customer base tenfold between its launch in 2015 and June 2020, adding around 9 million customers in the first half of 2020 alone. Detailed Chinese lending statistics by firm size are difficult to come by, but very rough estimates put five-year-old MYBank’s market share of Chinese SME lending at around 20%.

Ant Financial issued RMB 422 billion in small business loans as of June 3, according to its Ant’s prospectus, while the online SMB credit market for loan sizes below RMB500,000 reached RMB2 trillion in 2019, according to Oliver Wyman estimates quoted in the filing.

Three lessons learned from a decade of fintech lending in the US and China

1. Fintech lending can be a vehicle for financial inclusion

Even before the pandemic hit, a growing body of empirical research focused mostly on the US supported the claim that fintech lending can have inclusive outcomes (For example, see Jagtiani and Lemieux, 2017 and for China Hau et al., 2018). Policymakers in both the US and China recognized this potential early on by adopting a relatively hands-off approach during the sector’s formative years.

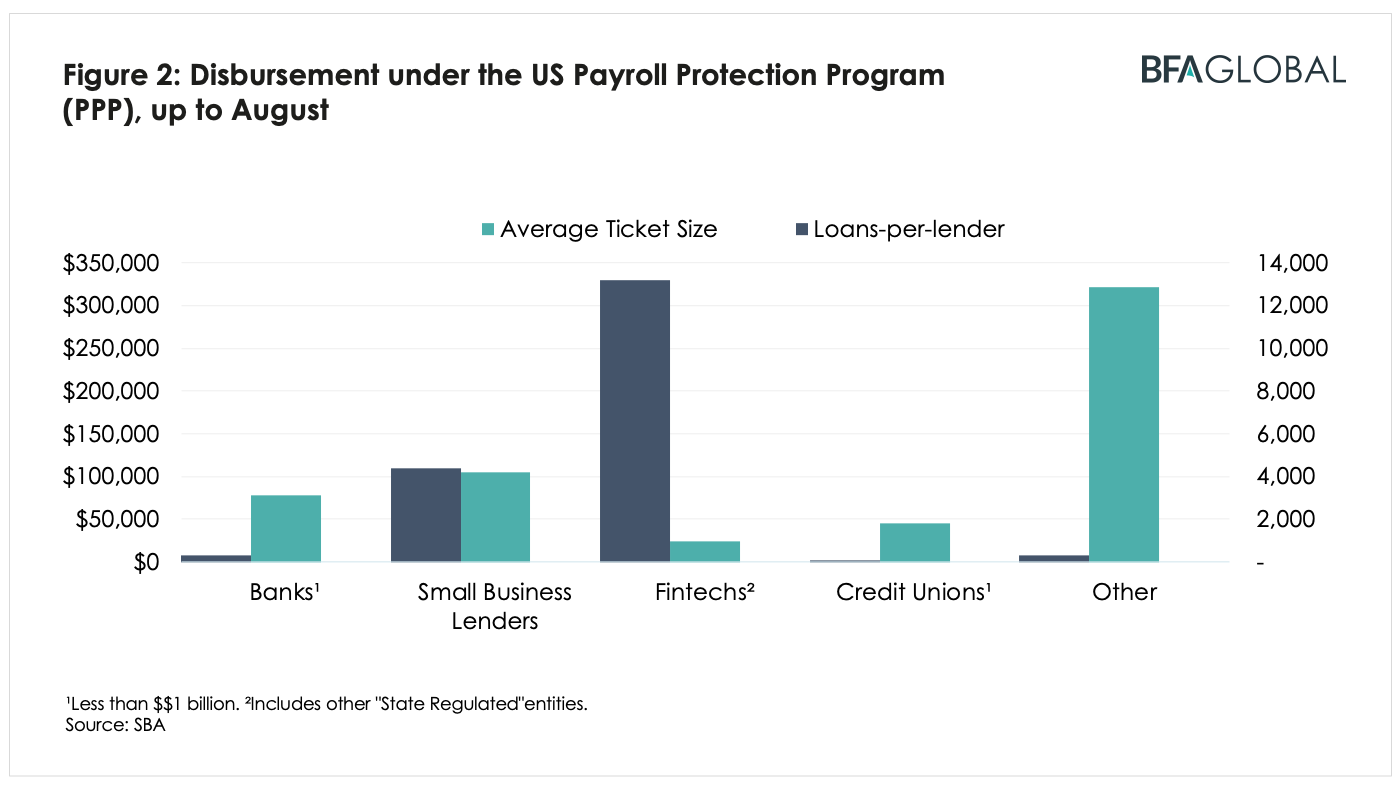

Fintech lenders have also played a prominent role in recent COVID-19 financial relief programs, at least in the US (and also the UK), demonstrating their value as an inclusive channel for targeting financing to hard-to-reach small business segments. The US government included fintech lenders from the outset in their Coronavirus stimulus programs, though they were slow in granting them formal lending authorization. Once authorization was obtained, fintech lenders were quick to disburse funds using their streamlined underwriting and digital distribution channels, whereas banks reportedly struggled to adapt to the sudden rush of Payroll Protection Program (PPP) loan applications and the urgency for fast turnaround. By August 2020, fintech lenders had collectively issued the most loans per lender in the smallest amounts compared to all other lender types (see Figure 2 below), while mounting dissatisfaction with banks had apparently led many MSMEs to consider switching lenders.

Source: SBA report 08/2020 available here

2. Competition between fintech lenders and incumbents need not be zero sum

Until the pandemic, MSME lending in the US (and also Europe) appeared to be settling into a bifurcated market equilibrium wherein fintech lenders specialized in credit to small, subprime and unscored borrowers, and incumbent banks concentrated mainly on low-risk and large borrowers. The division reflected different risk appetites and return expectations as well as comparative advantages in their respective market niches. A 2019 study using US data has found that fintech lending complements bank lending for small loans but competes for higher quality borrowers on similar terms.

The pandemic has shaken this up this. For one thing, it has severely tested the business models of lending platforms that rely on flighty wholesale funding and securitization. Government stimulus in the US has made up for some of the shortfall in liquidity, yet lending volumes are still significantly down compared to pre-pandemic levels, and valuations have fallen sharply. Although many small- and medium-sized fintech lenders struggled with intensifying competition well before the crisis, the acute financial stress has pushed many into a “partner or perish” situation.

Thus, two of the largest US SME-oriented platforms were acquired in 2020 by bigger financial institutions (Kabbage by AMEX, and OnDeck by Enova). Others have strengthened Platform-as-a-Service partnerships with banks to secure more stable sources of financing, including partnerships with smaller US community banks that are able to tap into a much larger customer base than they otherwise would have, as a result of using fintech lenders’ digital distribution platforms.

While the threat to banks from fintech lenders has diminished, at least in the near term, incumbents in both the US and China now face a more serious challenge from BigTechs. These companies have leveraged their strong balance sheets and vast merchant networks to ramp up lending to MSMEs on the back of surging e-payments and e-commerce during the pandemic. Their strategy of offering MSMEs holistic digital transformation support and using incentives such as waivers on merchant fees, free advertising credit, or free cloud services is already bearing fruit, for instance, in the form of higher stock valuations. This will likely pay dividends going forward. As more and more MSMEs join their ecosystems, the network effects created by harvesting data and cross-selling fintech services will grow stronger, as will BigTechs’ competitive edge over banks and fintech lenders. Thanks also to the sudden pullback in lending by incumbents and fintechs, BigTechs are well-placed to accelerate the trend towards “embedded finance” that was already underway before the pandemic.

For fintech lenders, the impact of the pandemic so far is less encouraging. While they have demonstrated the ability to outcompete banks on speed, inclusion and customer experience, their lack of a stable funding base is a major source of weakness—unless they can partner with incumbents. For banks, a marriage of convenience with fintech companies may be their best bet to fend off the challenge posed by BigTechs. As already seen in the US, such arrangements can take various forms that do not necessarily entail cannibalizing banks’ core businesses.

3. In a sector prone to manics and panics, sound and predictable regulation is key

Fintech lending inhabited a regulatory grey zone during its formative years in both the US and China—neither formally sanctioned nor prohibited. Where specific rules did exist, they were not strictly or consistently enforced (For example, P2P platforms in China were formally authorized as “information intermediaries” only after 2017, and as such were legally prohibited from assuming any credit risk themselves.). These open conditions provided fertile ground for experimentation and entrepreneurship but not for scaling up lending activities, owing to the relatively low levels of business digitization and funding available at the time. That changed in the early 2010s with the confluence of ultra-loose monetary policy and the resulting search for higher yield by US institutional investors and by an emerging class of Chinese retail investors.

The ensuing alternative credit booms were tolerated by authorities in both countries on the view that the platforms were fulfilling unmet borrowing needs and that systemic risks were contained. While we have already recognized the inclusive outcomes as the first learning, lax oversight did contribute to excesses and abuses.

In China, the so-called “internet finance” boom reached an inflection point in 2015 when widespread fraud in the industry was uncovered, including the revelation that a leading P2P lender, Ezubao, was operating a Ponzi scheme. Trust in the platforms evaporated, and from 2016 onwards, Chinese regulators progressively tightened regulation to the point where practically all business models save for PaaS and ecosystem lending were banned. While a forceful response may have been needed to weed out rampant misconduct, entrepreneurship and investor confidence suffered a heavy blow from the sudden and blunt regulatory intervention. Prevailing investor sentiment toward P2P lending suggests the dampening effect will linger for some time. Leaving aside BigTechs, we therefore do not expect fintech lenders to play a major role in China’s COVID-19 recovery, even if regulation is relaxed in the near-term to encourage this.

In comparison to China, fintech lending regulation in the US has been relatively stable and broadly supportive. Existing market conduct rules helped to avoid many of the excesses seen in China. Nevertheless, because of the difficulty of obtaining federal banking licenses, there has been considerable regulatory arbitrage, whereby lending platforms “rent” bank charters from small community banks in lightly-regulated jurisdictions such as Utah. Unable or unwilling to book loans themselves, they operate “originate-to-distribute” models funded overwhelmingly by short-term capital–an arrangement reminiscent of the collateralized debt obligations implicated in the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. This exposes fintech lenders to the violent swings in investor sentiment seen during the pandemic. Overall, the shaky legal footing and uncertainty surrounding future regulatory treatment likely weighs on the sector’s growth potential, and certainly limits its capacity to support COVID-19 recovery.

The experience of regulating fintech lending in each country has ended up very differently but we see three common key takeaways.

- First, as Chinese, and to a lesser extent US, examples have shown, the risk of mis-selling and mismanagement by inexperienced or unscrupulous lenders cannot be understated. Like capital markets in general, and unlike other digital financial services such as insurtech or e-payments, fintech lending in particular has the potential for destabilizing manics and panics. Allowing the industry to develop outside of the regulatory perimeter, whether out of benign neglect or wilful blindness, may be more harmful than setting certain ground rules at the outset, even if they are “sketchy,” and then adjusting regulation as the industry evolves.

- Second, if a hands-off approach is inadvisable, then so too is heavy-handedness at the first signs of trouble. The Chinese example shows that sweeping clampdowns can seriously harm trust and confidence in the fintech lending model, which may be difficult to revive once the negative association has been fixed in the publics’ minds. A sledgehammer approach is unlikely to be effective, both given the magnitude of pent up demand for retail investing and borrowing, as well as the ability of fintech lenders to “pivot” in response to changing circumstances. To avoid the game of regulatory whack-a-mole that has unfolded in the US, financial authorities should therefore create some safe spaces for fintech lenders to play and grow (e.g., in a regulatory sandbox) rather than seeking to quash activity altogether.

- Third, given the cross-cutting nature of fintech activities and the ability of technology firms to shapeshift as conditions warrant, regulation needs to have a broad purview encompassing diverse jurisdictions and policy domains, from financial services to commerce and telecommunications. Taking a narrow view of fintech lending – for instance, as simply an innovative form of credit intermediation – overlooks the value that synergies with non-financial or non-lending activities creates.

The main lesson for regulators from fintech lending in the US and China should be to pursue a Goldilocks strategy: neither too lax nor too restrictive; neither too reactive nor too prescriptive; and neither short-sighted nor narrow in purview. Striking the right balance will be challenging, no doubt, but taking no action or suppressing fintech lending may likely produce even worse outcomes: the status quo, where incumbent lenders are unwilling or unable to serve MSME finance needs, or a BigTech takeover, where big techs leverage their inherent data strengths to undermine the banking system.

A deliberate and concerted effort may be needed to forestall a situation in which the pandemic snuffs out nascent fintech lenders while entrenched incumbents remain disinclined to assume the costs and risks of MSME lending. Likewise, permitting BigTechs to expand aggressively might advance financial inclusion objectives, but this must be weighed against the potential cost of undercutting domestic competitors, undermining policy autonomy or even surrendering data sovereignty. Striking the right balance between these two extreme scenarios will require careful and forward-thinking regulatory approaches.