Three Barriers to Smartphone Readiness in Emerging Markets

Co-authored with Javier Linares

Having a smartphone doesn’t mean you’re ready to go digital

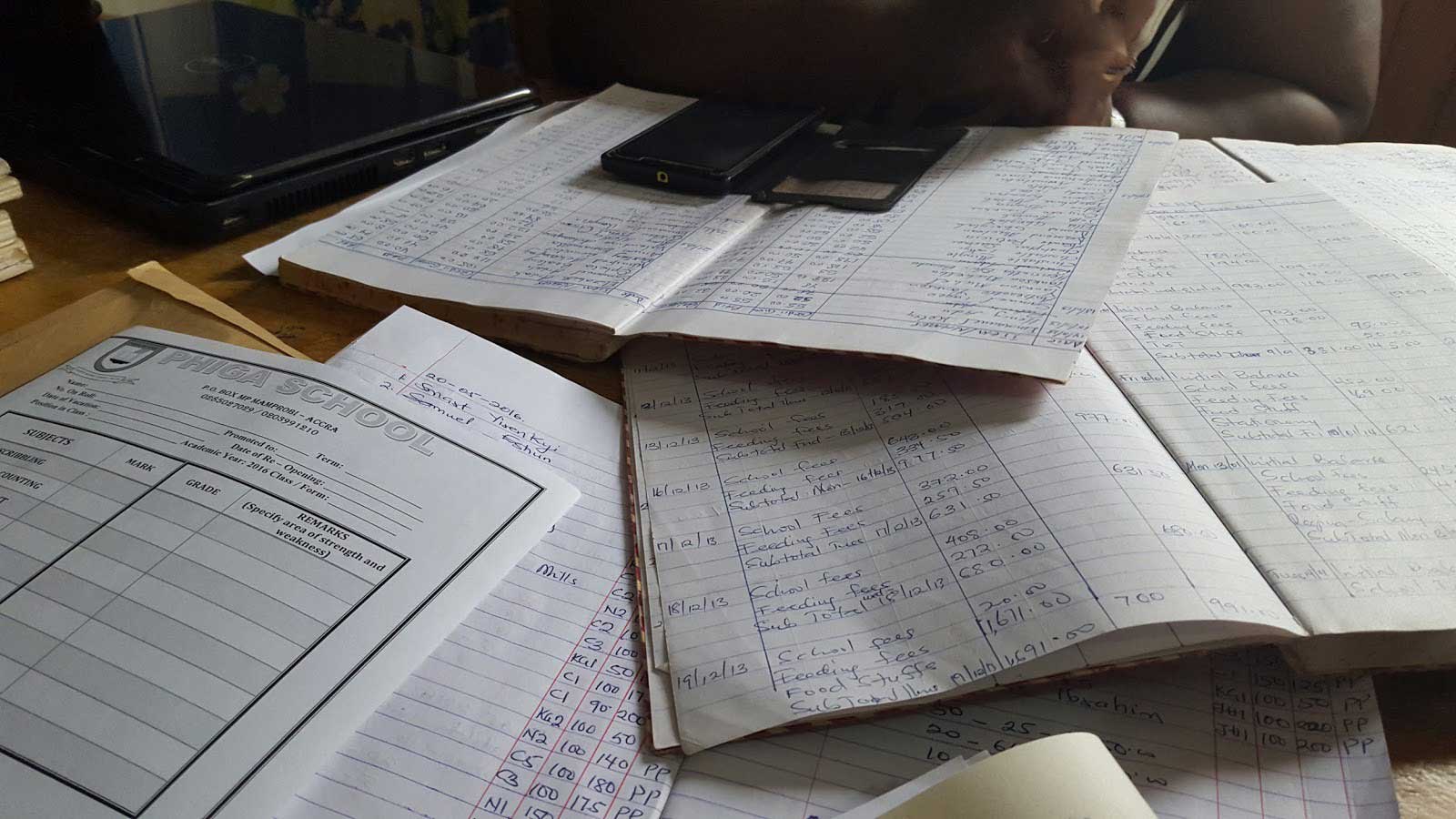

The FIBR program seeks to leverage the fact that smartphone ownership is increasing, and that the adoption of these mini computers opens up a world of new data that was previously invisible — locked in paper ledgers or in the minds of small business owners and sales agents.

One of the FIBR partners from our work in the MSME sector is Sokowatch, an e-commerce platform for informal retailers in urban Africa. Of the 5,000 retailers that Sokowatch reaches in Kenya, slightly more than half of these own smartphones. For this reason, Sokowatch and FIBR jointly developed a smartphone-enabled solution for ordering goods and accessing credit which has been rolled out to 150 pilot merchants. Through this pilot, we have discovered that barriers to app adoption are plentiful.

As Ignacio Mas pointed out after a visit to a Sokowatch merchant, having a smartphone is not the same as being smartphone-ready.

Three barriers working against smartphones adoption

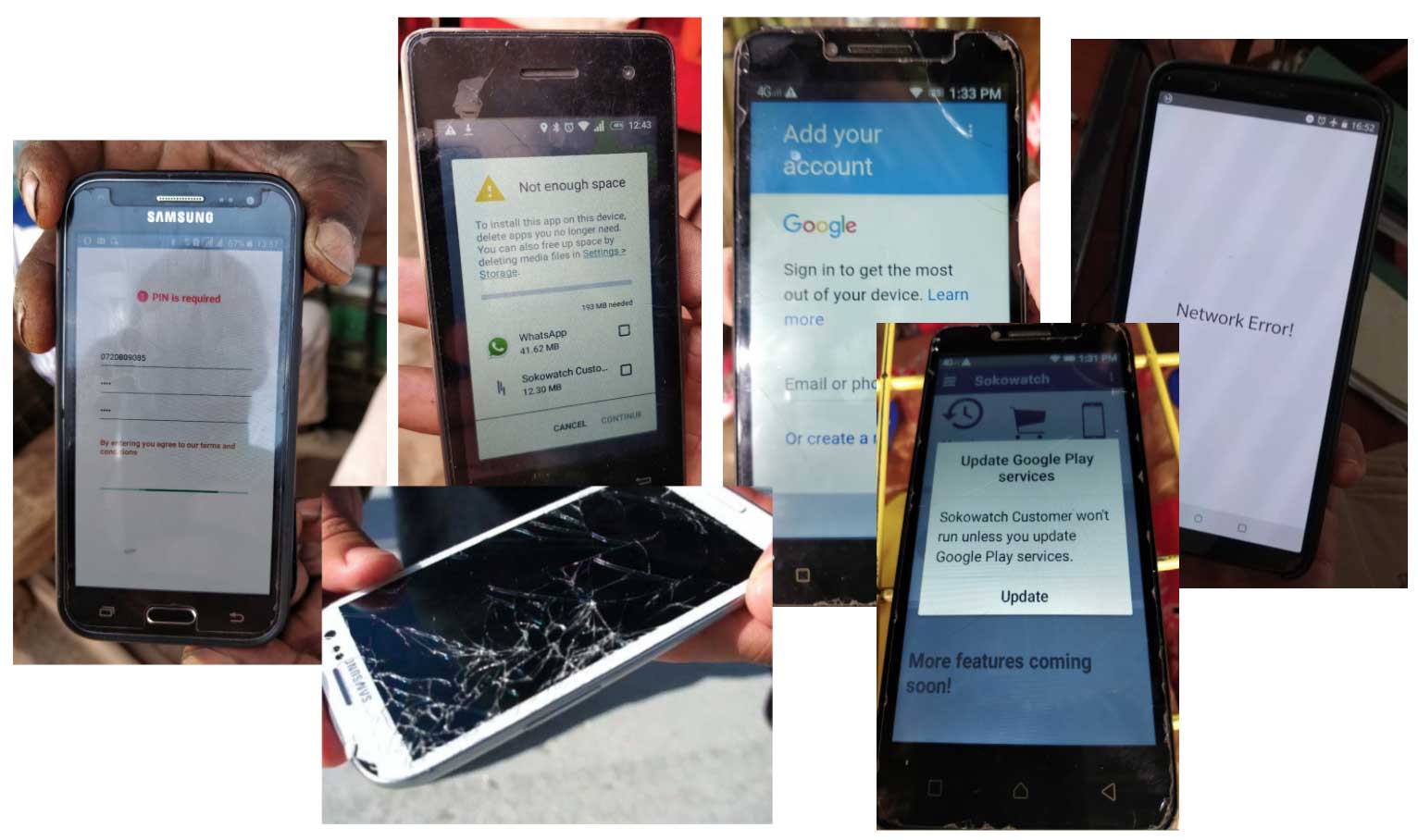

Phones are older, damaged, or have limited storage capacity.

Secondhand or budget smartphones are readily available in African markets, and their prices are dropping steadily. Jumia, one of the largest e-commerce platforms in Africa, reported that the average smartphone price has dropped to US $100 in Nigeria and US $96 across other African markets. In Kenya, several new smartphone models are available for as little as US $30.

While this is promising in terms of access, entry-level or secondhand smartphone models are likely to be older or damaged, and may have faulty hardware, outdated operating systems, and lower data and storage capacity. Further, screen sizes are often smaller and support lower resolution than newer models.

Network connectivity is spotty, and data bundles remain out of reach. The price of data and SMS packages remains high. According to the ITU, the cost of a standard monthly mobile-cellular package exceeds 5% of GNI per capita in more than two-thirds of African markets. Thus, a majority of low-income smartphone users are offline much of the time. Apps should consume low levels of data and allow for offline functionality.

Many users don’t know how to download or use apps. Most Sokowatch merchants that own smartphones use them for social media (WhatsApp or Facebook) or for basic phone calls. The majority are not aware of the Google Play Store or how to download an application. Learning to use a smartphone requires a wealth of digital knowledge, especially when combined with learning to navigate the internet.

To download an application, users must have an active data bundle, and must execute a painful, multi-step process. First, she must navigate to the Play Store, register with an email ID (which may require opening an email account), download it (sometimes requiring the removal of another app if insufficient storage is available), and finally, register for the desired app (assuming she knows the difference between registering and signing-in). Each of these steps adds friction to this painful process, meaning that most first-time smartphone users rely on physical networks they trust, such as a friend, a family member or an employee in a cyber cafe for help installing applications via SD cards.

In the next post, we will explore how FIBR and Sokowatch are working together to overcome these barriers for merchants.