Forces and uncertainties shaping future fintech ecosystems

Blog 3 of the Recovtech series, this post written in partnership with members of the South Africa Recovtech team.

The first blog in our Recovtech series defined the fintech ecosystem as the set of inter-relationships between innovators, incumbents, regulators, capital providers and service providers, in a country that gives rise to fintech innovation. As we discussed in the second blog, a fintech ecosystem may be relatively dense or sparse. However, its size or depth may matter less for outcomes than whether it is ‘fit for purpose’. The purpose we are considering in this series is contributing to inclusive growth.

In this blog, we consider some of the general forces and uncertainties that are shaping national fintech ecosystems, giving rise to different scenarios for their futures. Next, we’ll look at how this translates into inclusive growth.

Forcing driving fintech innovation

In common with financial systems in general, fintech ecosystems are being moulded by long-term forces which are well beyond the control of any individual players in a particular ecosystem. For example, fintech ecosystems have already been, and will continue to be, influenced to some extent by all five of the megatrends listed in the 2020 UNDESA World Social Report: demographic change, urbanization, income inequality, climate change and technology change. Of all of these, technology change has been the most direct driver of fintech innovation so far — in particular the conjunction of rising access to data, the diffusion of cheap computing infrastructure and data science tools and the growing interoperability of fintech platforms. These may be encapsulated as the three “Great Opens.” They are exemplified, respectively, by the movement towards open banking and finance, the proliferation of alternative credit scoring solutions and the move away from tightly-controlled payment schemes, towards interoperable digital networks.

The Great Opens have been instrumental in enabling the integration of financial products and services into a growing array of non-financial services. This movement towards “embedded finance,” the fourth technological force driving fintech innovation in addition to the three Great Opens, started with the integration of payments into e-commerce platforms (e.g., PayPal and eBay in 2001, and Alipay into Alibaba in 2004), and then progressively into other platform-based business models, from social media (e.g., WeChat Pay) to ride hailing (e.g., Go-Pay by Go-Jek in Indonesia). Integrated lending and insurance are being added to the mix as well; for instance, flexible finance at the point of sale, on-demand health insurance at doctor visits or mortgages offered in a home-buying app.

Several commentators see consumer preferences congealing around ubiquitous, frictionless financial “experiences” delivered at the point of need, which would render traditional standalone products increasingly outmoded.

Just as demand for embedded finance is on the rise, so too is demand for alternative finance: the various debt and equity capital-raising models emerging outside of traditional financial systems, such as P2P lending and equity crowdsourcing. We consider this the fifth major force driving fintech innovation going into COVID-19 recovery. According to the latest Cambridge Center for Alternative Finance (CCAF) benchmarking study, the volume of alternative finance activity has grown exponentially since taking off in earnest after the global financial crisis. Although activity has been overwhelmingly concentrated in the UK, US and China to date, alternative finance has started gaining momentum in other regions in recent years. It should continue to gain traction going forward on the back of the three Great Opens, which provide critical inputs for alternative finance models, and by capitalizing on the embedded finance force, which will unlock new sources of capital and demand for funds.

Notwithstanding pandemic-induced economic headwinds, the forces behind fintech innovation in general remain strong. It may even be accelerating as a consequence of social distancing and lockdowns. The pandemic has highlighted the value of timely and accessible data, be it for contact tracing or tracking pandemic relief. Contactless and frictionless financial services have taken new meaning as essential for containing transmission of the virus. As well, alternative finance has become a lifeline for credit-starved businesses seeking to access government financial relief, with fintech lenders picking up the slack from banks that have pulled back on lending to higher-risk segments, much as occurred in the wake of global financial crises.

Uncertainties mediating how Great Opens play out in different ecosystems

How will these forces shape fintech ecosystems in the short to medium term? That depends on the nature of the individual ecosystem, which is where our fintech forest framework from our second blog comes in.

The three Great Opens have a direct bearing on the axes by which we classified ecosystems into forest types: innovation capacity, market size and financial depth. Thus, there is solid evidence to suggest that greater openness, in the sense of the three Great Opens, begets more innovation. Embedded finance, in turn, promises to make low-cost financial services available to users on a variety of platforms, in the same way mobile money has served as an on-ramp for un-/underserved populations to other digital financial services.

The instrumental role of Chinese BigTechs in increasing financial inclusion in that market further underscores this point. In dollar terms, one recent analysis estimates the opportunity from embedded finance to be over $7 trillion in ten years’ time — twice the combined market capitalization of the world’s top 30 banks today. Finally, alternative finance has the potential to raise financial penetration by unlocking new sources of capital and bringing in un-/underserved borrowers such as medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Again, the example of Chinese “internet finance” as a vehicle for driving financial inclusion is illustrative, even if lapses in oversight eventually undid many of the gains.

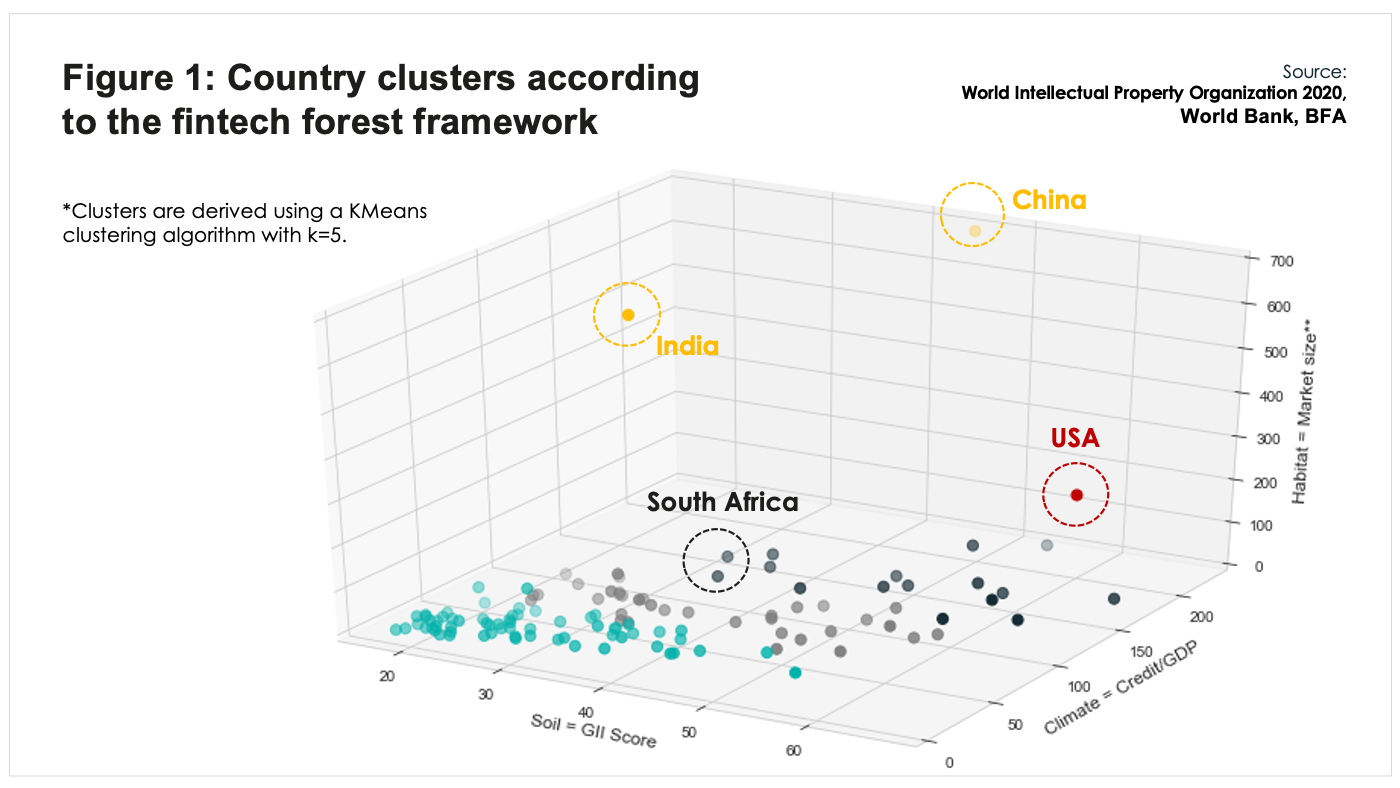

Were we to assume that the trends towards greater openness, embeddedness, and alternative finance continue unimpeded, we might expect ecosystems to gradually converge toward the Redwood or Banyan forest archetypes, since these occupy extremes of these axes (see Figure 1, explained in blog #2 of this series). Yet that would be an implausible outcome. Forces are subject to inertia and path dependency of local institutions and infrastructure, over which policy makers and regulators have limited influence, at least in the short to medium term. They do, however, have some latitude over the speed of opening and the forms it takes.

In particular, policy makers control the degree of openness to the flow of data and technology into and within a national ecosystem, as well as the barriers to market entry faced by alternative players and platforms. Their choices of policy settings and regulations along these two dimensions will partly determine the impact that these forces will have on a given ecosystem. We first unpack these sets of policy choices before sketching out corresponding migration scenarios.

Data openness: Since data is the ‘oxygen’ of the digital economy, it may seem that more openness to data flows is always better; but in fact, data openness alone without trust or oversight can lead to abuse which may undermine confidence in the digital ecosystem and slow its growth. This is not just about whether there is data protection or cyber security legislation in a country; it is also about how it is enforced and perceived. Also, choices about who has to open data to whom will be important here.

Most privacy laws cover natural persons but not businesses. Open banking requires that banks open access to their data on some basis, but it does not apply to non-bank entities. Another aspect of openness here is about cross border flows; the basis on which these are allowed will affect the openness to outside solutions. For instance, data localization laws, which restrict cross-border transfers of data, may make it impossible to use certain technology, such as cloud computing, if the infrastructure is not available locally.

Market openness: Market “openness” is in large part a function of licensing regimes which define the types of entities that are allowed to start up in a jurisdiction and how they can play (e.g. is there special provision for digital banks or for crowdfunding platforms?). The absence of a clear law requiring authorization in a new niche may leave the space open for entry (in common law regimes at least), but it may also create regulatory uncertainty as an overhang on growth. Clear rules and authorizations are especially important for embedded and alternative finance to realize their potential.

US BigTechs have been hesitant to enter financial services outside of payments in large part because of the regulatory risks and uncertainty it entails. Market openness is also about whether it is easy for foreign entrants to set up and provide their services in a particular market or for foreign foreign talent to enter and take up employment.

Viewed through the lens of the fintech forest framework, we see data and market openness as the ecosystem’s “pollinators” since they ultimately determine whether and to what extent new ideas can spread. Regulation and policy enablers, the “roots” in this analogy, determine whether innovative ideas take hold and sprout into businesses or business models. Thus, policies such as open banking (which generally requires banks to share customer data, with their permission, with third parties and for those third parties to register with a particular regulatory or supervisory authority) or fintech charters, which respectively facilitate data and market access, make it easier for entrepreneurs to create and launch new businesses and business models.

Migration scenarios based on forces and uncertainties

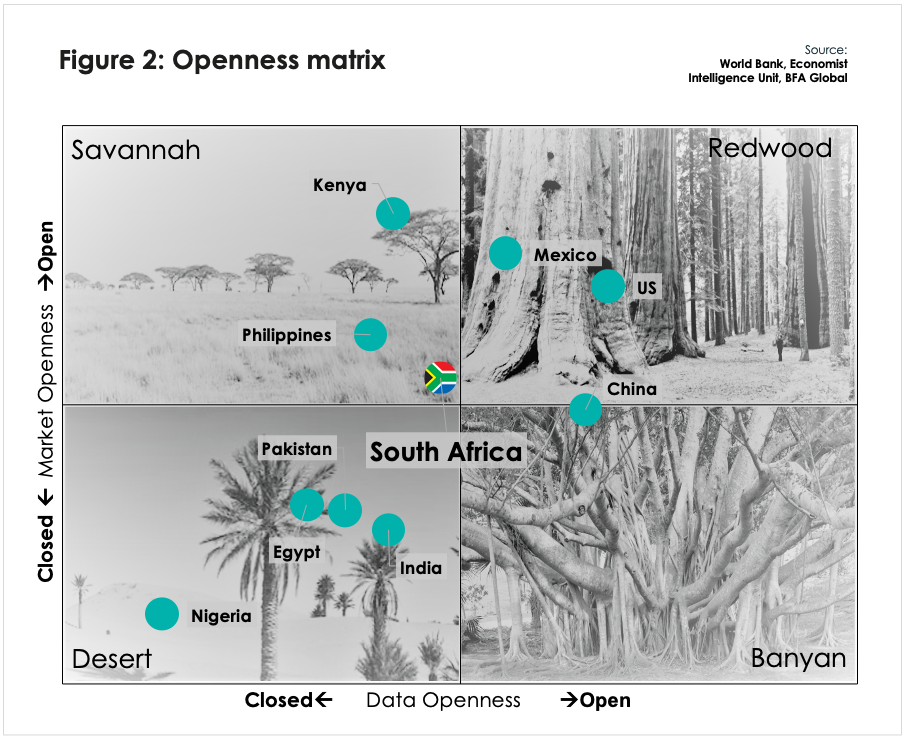

The choices of policies along each of these dimensions are not discrete. They interact in complex ways — for example, data openness may enable new startups to emerge and make use of data, but the degree of market and financial openness will affect what forms they may take. The outcome from this interplay will affect which financial players are more likely to be the dominant species in the future. To see this interaction more clearly, we linearized the first two dimensions onto a scale of less to more openness using a combination of variables measuring data flow and market entry (We blended quantitative and qualitative indicators from the Economist Intelligence Unit’s (EIU) Global MicroScope 2019 and World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business ‘Getting Credit’ sub-index, as well as an assessment of the state of open banking based on criteria developed by the Bank for International Settlements), and place each on its own axis, as visualized below.

If we envision for simplicity dividing each axis into ‘high’ and ‘low’ zones, four different zones result from the possible combinations which align with the “forest” groupings we derived in blog 2. We’ve plotted a number of countries based on their scores in the two openness scales.

Incumbent financial institutions are likely to remain dominant in the desert ecosystem quadrant (lower-left). Not only is it hard for new challengers to enter this type of market, but the lack of trusted data flows mean that data will remain in the hands of those who already have it, such as banks. Incumbents in this space may sustain innovation, but they have fewer incentives to disrupt the status quo.

However, if data flows are opened up while keeping market entry relatively closed (i.e., a move horizontally rightwards), the environment then becomes likely to force entrants who can use the data into different relationships with incumbent financial institutions. The fintech and BigTech players that are able to sell their data and technology services to incumbent financial service providers, even if they themselves cannot assume risk directly, will do well in this space. Those that also control vital data sources, such as e-commerce platforms or mobile network operators, will thrive. Smaller startups that lack the scale, scope and ties to the financial sector will struggle.

It follows that the more concentrated financial systems, with fewer opportunities for partnerships, are likely to yield sparser fintech ecosystems. This broadly describes the situation in China, at least following the strict enforcement of rules curtailing risk taking by fintech companies from 2017 onwards. For example, Ant Financial relies almost entirely on incumbent bank funding to originate loans; it retains only 2% of assets on its balance sheet. Even so, it enjoys superior market power across the rest of the value chain thanks to its control of the customer relationships and resulting data.

If a market is open in both dimensions (i.e. the top-right Redwood quadrant), both data and capital can move more freely, meaning new players are able to access data and assume risk without having to rely on incumbent financial institutions for either. The five forces would have the most direct influence on this ecosystem compared to others, which would arguably benefit fintech companies most since BigTechs and incumbents would have a harder time monopolizing data and capital, respectively. Powerful new players may emerge and reshape the sector, but no one species is likely to dominate. Rather, the competitive landscape is likely to be relatively dense, diverse and dynamic, much like the Redwood ecosystem of Silicon Valley.

Finally, in the savannah quadrant (open markets but closed data), new financial firms and business models may set up with relative ease but face difficulties procuring data from outside sources, and must therefore manufacture their own. Those with ancillary lines of business that generate relevant data (e.g., mobile money transaction data owned by telcos or e-commerce merchant sales data owned by platforms) will have a competitive advantage. Super-platforms like Amazon or Alibaba may come to dominate if an open licensing regime allows them to provide financial services directly, rather than merely offering technology services to incumbent financial institutions (as in the lower-right quadrant).

Calibrating the policy mix for a post-COVID world

Of course, this framework is conjecture. The point is that policy choices over data and market openness have an important bearing on the nature of the ecosystem, in large part by determining the conditions and constraints that will allow certain species of fintechs or BigTechs to thrive and others to flounder.

Regulators and policymakers across the world have adjusted their policy settings to support the pandemic relief, as a global COVID-19 Fintech Regulatory Rapid Assessment Study by CCAF has shown, yet few have targeted data or market openness per se as part of this effort. That may change as policymakers shift their priorities towards restarting economic growth. A greater focus on fintech policy in general will likely be needed given the rapid adoption of digital commerce and digital government because of lockdowns and social distancing. The majority of respondents to the CCAF survey affirmed as much.

The pandemic has also sharpened the trade-offs between different policy mixes along these two dimensions of openness. On the data axis, increased digitization implies a larger “stock” of customer data that can be leveraged for digital financial services. The quadrant or “forest type” that characterizes an ecosystem will determine which type of player ultimately benefits from this windfall. It may translate into a significant competitive advantage for the main data holders unless they can be induced to open up access to others. In China, for instance, BigTechs such as Ant Financial and Tencent have seen their user bases swell on the back of the digitization drive, providing a significant boost to their fintech business (SME lending in particular, a story we will revisit in blog 5).

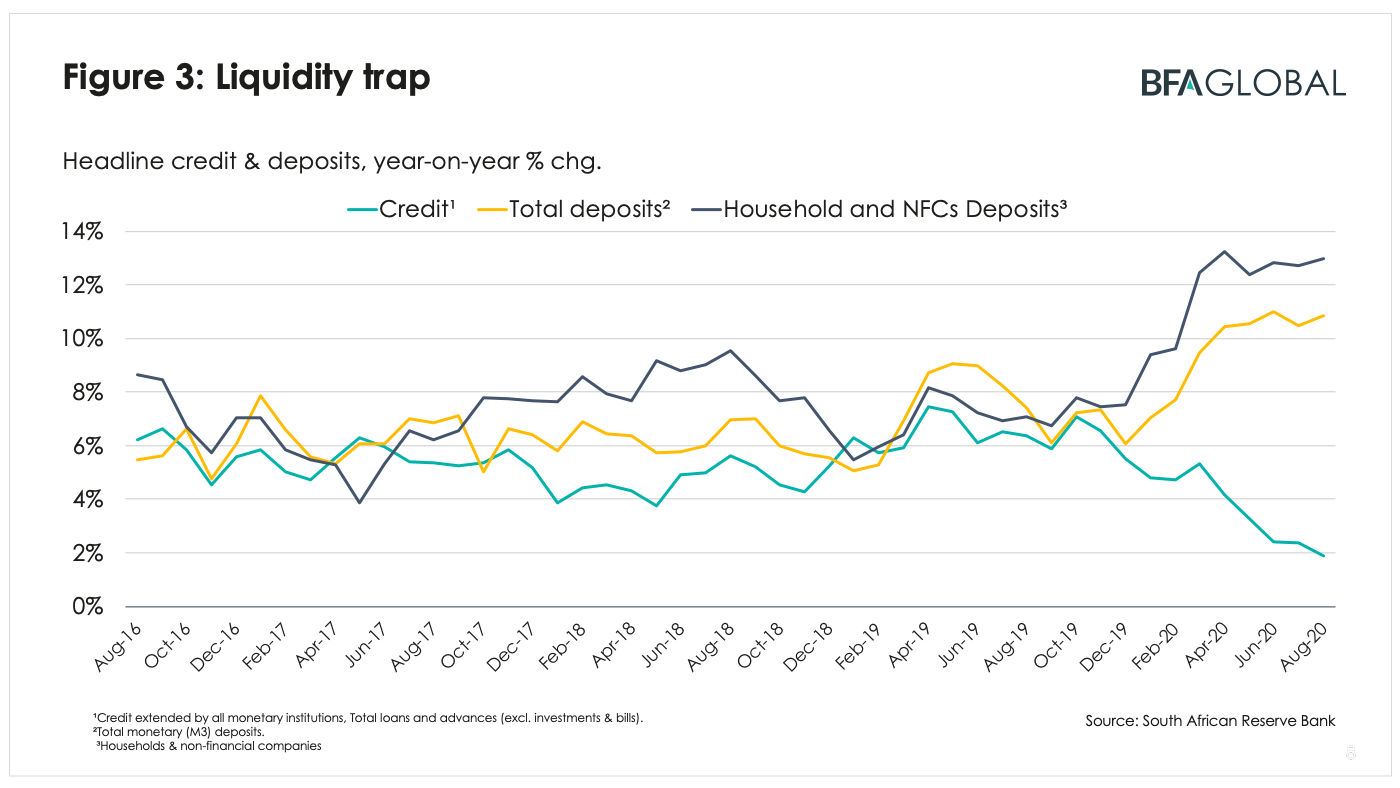

Likewise, the COVID-19 crisis has led to a massive reallocation of liquidity in the economy towards insured bank deposits and away from higher-risk activities such as fintech lending. In the US, for example, “marketplace lenders” (US terminology for fintech lending) experienced a sudden halt in funding to their platforms during the pandemic, putting many at risk of failure. Meanwhile, banks in the US, China and South Africa have been unwilling or unable to on-lend the influx of deposits to credit-deprived businesses at sufficient speed or scale.

In South Africa, this can be seen in the sharp decline of overall credit to the private sector (see Figure 3). This dislocation risks entrenching the power of incumbents and undermining the inclusiveness of recovery, if liquidity remains trapped in traditional “safe havens” and out of reach of small, higher-risk segments. This seems likely in ecosystems where fintech companies face major barriers to licensing or risk-taking (i.e., the lower quadrants of the openness matrix).

One of the key questions therefore facing policymakers is to what extent they can rely on incumbents alone to drive post-COVID recovery. If they are convinced incumbents can do this adequately, it may be a feasible choice to hold off on opening. If not, policymakers will need to recalibrate their policy mix. Either way, finding ways to channel this liquidity responsibly back into the economy is now a central task of economic policymakers. Their choices around the dimensions of openness discussed here will play a big role in shaping the ecosystem and affect which players become dominant. While uncertainty is high, the stakes are higher still.