Work with What You’ve Got to Offer MSME Credit

The Case in Kenya

Starting from the Microfinance Bill in 2006 up to the runaway success of the mobile lending and saving solution M-Shwari in 2013, Kenya has been at the forefront of furthering access to finance. However, Kenyan MSMEs — like those around the world — still struggle to obtain access to formal financial services. Our research shows that MSMEs (particularly small shops or “dukas” which have been the focus of our research) rarely access credit through formal channels and instead continue to rely on personal savings, savings groups, and friends and family. In 2016, a national survey found that 85 percent of unlicensed businesses and 76 percent of licensed businesses in Kenya obtained capital either from savings or by borrowing from family and friends.

Though access to credit is limited, our research has revealed that not all micro-retailers want credit. Some businesses operators are content as they are and do not aim to grow their businesses. However, those that want to grow need working capital for inventory, which is why almost one in two Kenyan MSMEs take out loans. This access to capital is crucial: one in three Kenyan MSMEs fail when they face related shortages.

Moreover, the success of MSMEs is critical to the Kenyan economy. According to the 2016 national survey, MSMEs contribute a third of the gross value added to the economy (KSh 1,780.0 billion out of KSh 5,668.2 billion). Of the gross value added, micro and unlicensed businesses contribute about 12 percent (nine percent and three percent respectively). MSMEs also account for total employment of 14.9 million out of about 28 million adults, of which 81 percent pertains to microbusinesses.

Given the importance of MSMEs, financial institutions, donors and the Central Bank of Kenya have all committed to enhancing access to credit to MSMEs. For example, in 2018, Co-operative Bank got a KSh15.2 billion (approximately US $152 million) preferential loan from the International Finance Corporation to fund lending to MSMEs. KCB Group also obtained a KSh10 billion (US $100 million) credit line from the African Development Bank for lending to small businesses starting 2018.

“$30 for 30 Days” Isn’t Enough

Despite the availability of these funds, credit for MSMEs remains expensive and difficult to obtain. Many lenders, especially those using digital channels, only offer extremely short-term loans of about one month with interest rates greater than five percent per month, far above the 13 percent per annum that traditional banks offer. While many MSME owners use M-Shwari and KCB-M-Pesa, the amounts are too small, the rates are too high, and the tenures are too short to make a difference in their businesses’ trajectories.

Barriers to Access Persist

When we ask about barriers to offering credit to MSMEs, financial services providers (FSPs) continue to cite the same challenges to explain the low levels of lending to MSMEs: high costs and high risk.

Banks, MFIs, formalized savings groups, and digital lenders unanimously report that it is extremely costly to serve MSMEs. It is expensive to administer the loan sizes they require, which typically remain below $350 for at least the first 5 years. Moreover, serving MSMEs is high touch, which also drives up costs. FSPs note that they need loan officers who know the businesses well and can visit them from time to time for due diligence, appraisals, and follow up to ensure proper loan utilization and repayment.

Given this cost structure, it is important for providers to achieve scale to bring down the average cost per loan. One bank had calculated that it needed to disburse KSh 50–100 million per week to MSMEs for the proposition to make business sense. This would represent growing the loan portfolio by 15,000 to 30,000 loans based on the average M-Shwari loan size of 3,300 per borrower.

In addition to cost factors, FSPs consider MSMEs to be risky given the high rate of failure in the sector and thus create additional barriers to access. To identify stronger candidates, many require between 6 months and 3 years of sales data to prove the longevity of the business. Few MSMEs can produce such data as most don’t keep consistent records. Bank transaction records could help, but even those retailers who have bank accounts either use them for both personal and business finances or let the accounts go dormant. Some FSPs try to ringfence — guarantee that funds allocated for a particular purpose will not be spent otherwise — the borrowed funds to ensure that they are not diverted away from the business. Others even require that MSMEs route all their receivables to their bank or mobile money accounts to ensure repayment.

Despite this chasm between supply and demand, there is a way forward.

Three Reasons for Banks to Use Supplier Digital Payments Data

1. Suppliers Generate Valuable Data

Although few MSMEs keep sales records, many make digital payments to suppliers that could generate financial histories. A wholesaler we spoke to in Nairobi — who serves about 400 to 600 dukas a day — reported that 60 percent of these MSMEs make their payments digitally. While this data is potentially extremely valuable, there are no incentives, processes or adequate consent formalities in place for FSPs or suppliers to utilize them. The wholesaler we spoke to concentrated on volumes and values of sales and did not even record the names or details of the retailers making the purchases. The financial institutions at the backend of the digital payments platforms can track the payments, but are not currently using this information to target products.

The FSPs that we spoke to have an appetite for alternative data collected via other players to bolster credit scoring for targeting MSMEs. With the right processes in place, FSPs could use these financial histories to target specific MSMEs that meet a set of repayment or volume criteria. This would help address the problem of perceived risk among MSMEs since banks would have visibility into the volume and regularity of purchases made by the business.

2. Digital Payments Channels Can Lower Operational costs

To address high costs, FSPs could provide pre-approved lines of credit to MSMEs via the suppliers. Suppliers could help provide due diligence, monitoring, and repayment infrastructure to defray FSP administrative costs. The same digital payment platforms that are currently being used to pay the supplier could also be deployed to interface with the MSMEs, thereby achieving greater utilization of the platform. FIBR partner Sokowatch is pioneering such a model by facilitating access to credit via their app-enabled e-commerce platform, which provides supplies to MSMEs.

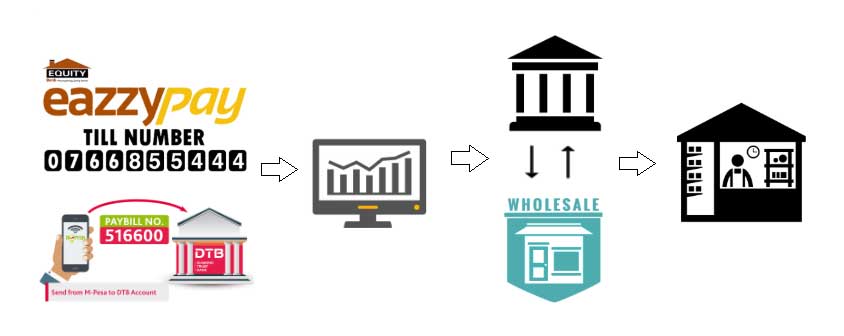

The model has four steps:

- The MSME uses these digital payment platforms when paying wholesalers or suppliers.

- FSPs such as Equity bank, Safaricom M-Pesa, and DTB that receive the funds at the backend analyze the payments data to target MSMEs.

- FSP use the data to provide in-kind credit to MSMEs by partnering with the supplier/wholesalers.

- MSMEs obtain goods from suppliers and pay FSPs later according to the credit terms.

3. There are benefits for all along the value-chain (for example, in-kind lend

- The above arrangement could benefit all actors involved, for example:

For the FSP

- Alternative credit scoring data

- Funding is ringfenced to buy inventory, ensuring it is not diverted

- FSPs can use its existing digital channel for loan applications creating greater usage for existing digital platforms

- Interest and processing fees

- Potential scale in lending small loans to achieve economies of scale

- Meeting lending targets

For the Wholesaler / Supplier

- Customer loyalty

- Less frequent, larger purchases by MSMEs that tend to make more frequent, smaller purchases

- The potential for increased sales

- Assured payment

For the Retailer / Shopkeeper

- Credit for inventory as needed

While this model has clear potential, there are some aspects that need to be resolved. Most importantly, FSPs are concerned about the cost of following up with the MSMEs and ensuring repayment at an effective cost. While suppliers are a good source for data, our research suggests they cannot be relied upon to collect repayments. Further research and testing are needed to refine repayment mechanisms, but the idea of using existing digitized payments data is clearly worth exploring to create financial products with a stronger value-proposition for micro-retailers and for financial institutions.