Why Silicon Savannah is Unsustainable, and What to Do About it

By Jamie M. Zimmerman

Since the 2010 release of early speculation that applications and other tech development and programming could create and jump start private sectors and local economies, a world of hype, enthusiasm and investments (from venture capital to public and donor money) appears to be funneling towards app development and mobile hubs around the world.

Apps4D — a smooth acronym that evokes images of hip startups peppering the developing world and cutting edge tools used by the development community — sounds like the next big thing that I, an interloper from the digital finance field, could not have anticipated it receiving such a heavy dousing of reality at a recent Tech Salon in DC.

The Tech Salon unearthed early an uncomfortable paradox: the strong desire to dismantle a deepening digital divide (and see tech sectors built and thrive outside of Silicon Valley) pitted up against the rarely discussed reality of a market firewall that drastically limits the potential of an actual “app economy” in developing countries.

Digital is the next extractive industry; successful apps and developers — and the economic growth that would accompany both — don’t stay in the country because the system is stacked against them doing so.”

On the one hand, a clear and growing digital access and capacity divide is compelling increased investment in local digital and app development for spurring local entrepreneurial individuals and communities; jobs creation and skills building, particularly for youth and other disadvantaged segments; increased access to info and services; improved systems and business management; and ultimately tools that create utility that improves livelihoods. The proliferation of iHubs globally and the mLabs and mHubs sponsored by the World Bank are familiar examples of this approach.

On the other hand, recent eye opening research about winners and losers in the App Economy from Caribou Digital calls into question the extent to which App4D investments or efforts will actually lead to any real economic development in developing and emerging markets. They point to harsh realities:

- As a typical digital entrepreneur in developing markets, its nearly impossible to earn a comfortable living. Revenue flows are too low.

- All emerging markets together, including India, accounts about 1% of total revenues in this market. It is dominated by the West, particularly less than a handful of very powerful players.

- There is structural platform problem. Platform dynamics and economics are at play and creating a barrier. While local concepts and local people are best poised to create good and relevant apps for their markets, the global architecture make it nearly impossible to thrive.

One participant who has built a successful app development firm in Africa reflected that such companies, lots of time if they get big enough (over 50 employees), they move to consulting and “try to get deals with the West because that is where the money is.” While impact investing is seen as a potential channel to get good startups going, he lamented, “very few are getting the investment they need through that route.”

So much for Apps4D, right? Not so fast…

Despite some serious barriers to entry, scale and sustainability, participants brainstormed 5 ideas for supporting the app development industry in developing markets.

- Focus on the right kinds of apps that can really scale. “If it’s not going to touch a lot of people, then we are just spinning our wheels.” This will mean cracking the B2C business model. Caribou Digital research found that B2B is “the only way people are making money,” and scale on B2C has been elusive.

- Consider some form of certification program that local developers or groups could attain that would make them more eligible/competitive to win contracts or join larger partnerships. Perhaps this would help to integrate these developers and entrepreneurs into the large and potential lucrative proposals and projects in the development sector.

- Where possible, focus on government as contractor. This would require a serious rethink of e-procurement procedures where “locals can’t compete with major US companies.” But it could be a catalyst for local companies, and have the added benefit of embedding a culture of coding within governments. Change the way government looks at IT procurement and how it does tech and what it does for tech.

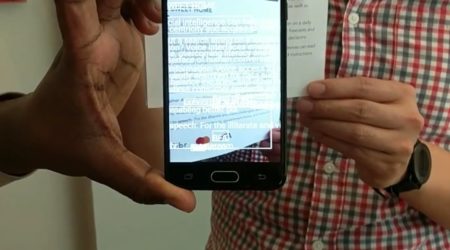

- Look out for Smartphones. The emergence and coming ubiquity of smartphones will necessitate new models and approaches. While preparing for that, companies can find hybrid solutions that work within the realities of the transition. For instance, Beyonic uses an API to make mobile app payments over mobile money. Dimagi creates supply chain software that uses smartphone apps in at the distribution level but SMS at the bottom of the chain where its more appropriate and accessible. FIBR examines existing or new models of financial inclusion through the data of business relationships captured by smartphones. Catalyst Fund, another BFA-managed project, seeks to spur innovation by bridging the pioneer funding gap for pre-seed inclusive fintech startups.

- Put a spotlight on the reality of financing. With “almost as much Venture Capital in this space in Finland as the entire continent of Africa,” more emphasis is needed on the dearth of developer financing in emerging markets. Despite there oft-cited Kopo Kopo success story, very few Series A deals have happened in Africa. Perhaps its time that we have higher expectations of the contributions and investments and capacity building among the largest global players, like Facebook and Google in these markets.

In the end, questions remain around what successful App economies should look like.

How do you build tech talent in emerging markets that create local markets, local value, and local visions of success? We need to change the narrative on what success is in this industry. If a Facebook-sized enterprise is unrealistic, then is a viable, sustainable, 50-person business is actually success in these markets?. At a minimum, surely if we are going to promote such skills acquisition we’d expect that person to make a decent living. Otherwise, a “digital fair trade” movement may be afoot.