A Quick Guide to Nanoprojects: A Lean Method for Product Design

At BFA, we have been working on an R&D program called FIBR. We partner with local businesses in Ghana and Tanzania to explore the potential for burgeoning technologies, such as smartphones and machine learning, which are increasingly available in these markets, to create opportunities to expand access to financial services. A major component of this program is to quickly assess the fit of a potential partner/product/solution for a relatively lengthy engagement.

Nanoproject Motivation: “Doing” beats “Planning”

While one seemingly attractive approach to partner selection is to meticulously design an airtight system at the outset, we have found that the best means to understand a system is by replacing a large portion of this planning with actively doing.

“In theory, there is no difference between practice and theory. In practice, there is.” –Jan van de Snepscheut

This approach is particularly useful in areas of high uncertainty where FIBR partners typically operate. It is with this spirit that we realized this concept of “learning through experiments”, designing a small set of preliminary, targeted engagements with concrete deliverables, which we refer to as a nanoprojects.

The nanoproject approach, described below in detail, has proven useful in selecting partners and de-risking collaborative product development across a wide variety of FIBR partnerships. Here are a few examples:

- Exploring a formal mobile-money-based school fee savings program in partnership with a payments aggregator that frees students, parents, and schools from the burden of effectively treating a child’s education as collateral for unpaid fees.

- Introducing a loan product into the cocoa supply chain, via a phone-based farming news service’s channels, to allow farmers to borrow funds for purchasing seeds & fertilizer at an agreed-upon rate to be paid in-kind at harvest.

- Analyzing transactional and auxiliary data generated by pay as you go (PAYG) solar energy systems to create improved payment plans and other financial products that better fit the needs of the PAYG provider and customers.

What is a Nanoproject?

In short, a nanoproject is an exercise in shortcutting the often-slow process of uncovering and understanding the risks inherent in a partner, product, and/or service.

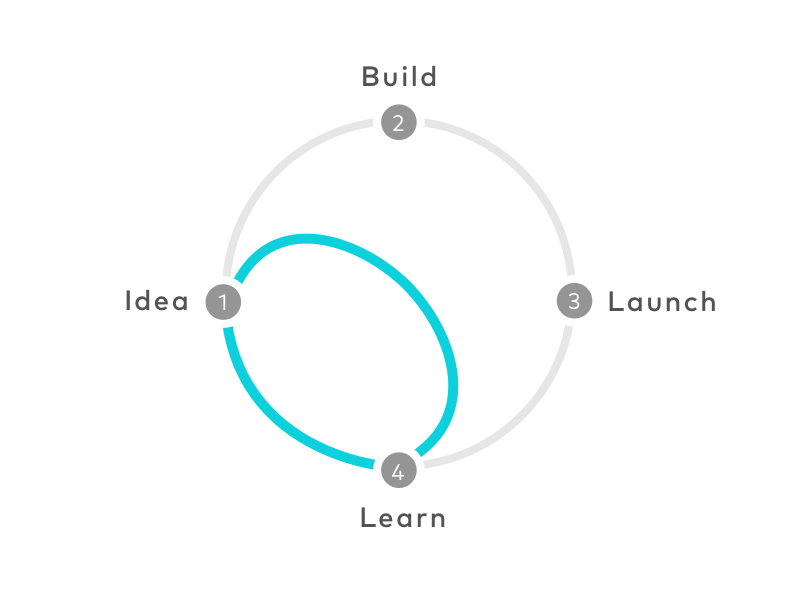

Nanoprojects seek to take the shortest path from an idea to the learnings generated through pilots and trials. Having these lessons in hand earlier and faster means the organization is exposed to less risk when introducing new products or services. In particular, nanoprojects seek to lower:

- Project Risk. Miscalculations around timing & scope, and how they affect budget and program deadlines.

- Partner Risk. The extent to which new products and services often include new partners and institutional configurations, issues of bandwidth, ability to communicate clearly and honestly, focus, technical capacity, and chemistry across and within organizations are each examples of risks relating to a new or existing partner.

- Product/Market Risk. Any issues related to product/market fit: the products’ targets, their problem(s), our solution(s), the channel(s) through which the solutions will be delivered, the utility or effectiveness of the solution in the real world, and the associated pricing.

- Technical Risk. Whether tools are readily available and/or can be built to accomplish the task in the time allotted. Also includes feasibility of new integrations, conversion of existing records to digital data, and the networks and other hardware available to the partners and the product’s targets.

(Note: the preceding list is not intended to be comprehensive, but to illustrate a key set of considerations in selecting a partner)

Rather than just assessing these risks on paper, the nanoproject is a 1-to-2-week engagement that tests some of the key risks in practice. This approach enables a thorough analysis of at least the most critical areas of uncertainty before moving into a fuller, months-long engagement.

“Risk comes from not knowing what you’re doing.”

–Warren Buffet

Nanoprojects Step-by-Step

In a nanoproject, we work with the partner to define mutual goals, select an approach that tests the feasibility of these goals and whether our hypotheses/assumptions are reasonable, and finally put it all together in a formal document that we deliver to the stakeholders.

Step 1. Defining Goals.

The first step is to pick out the highest risk areas, hypotheses, assumptions, and explore them just enough to begin to understand the risks and mitigation strategies. This is typically done via a web conference or, ideally, an in-person workshop, lasting approximately two hours. This artificially imposed time constraint forces the participants to focus on critical areas of co-scoping, and limits the introduction of “yak shaving” problems, in which a particular technology specification overshadows the core real-world goals of the engagement.

Step 2. Selecting a Testing Approach.

Depending on the goals identified in Step 1, one or more of the following methods may be deployed to test feasibility.

- Field Visits. If we identify one of the major risk areas as revolving around unknowns or misunderstandings within the customer relationship, a well-planned, structured visit to the physical space where transactions occur may be in order. This approach can be complemented with surveys and data analysis, which are described in further detail in a previous FIBR Briefing Note on the topic.

- Data Jam. A data jam can give a peek into the value and insights that could be produced by the partner’s data through exploratory analysis, rapid testing of predictive models, or a rough customer segmentation model. This is particularly effective for partners with a high volume of historical data already on hand, but the approach has also proven useful for those earlier on their data journey when combined with Field Visits or a Design Sprint.

- Design Sprint. We’ve found this approach to be effective when it’s not clear from the outset what other types of approaches to testing might be appropriate. There is a wonderful Google Ventures resource that contains more info on this topic, which we’ve adapted over many iterations to suit the needs of our work and our partners within the markets we serve. In short, the goal is to generate rapid learnings through a 5-day process, our version of which is summarized briefly here:

Day 1, Share. Select a team that maximizes the depth and diversity of the expertise and experience in the room (e.g. experts on context, user experience, tech implementation, business modeling, data, etc.) to describe the ecosystem surrounding the product or service in question and identify pain points in the process. End the day by selecting one pain point to focus on.

Day 2, Diverge. Each participant should spend time individually drawing a 3-step l solution to the problem identified on day 1. (protip: using thick markers on index cards helps to keep this process focused on the major features and less on the details of UI) Next, each participant should then briefly present a description of their solution, and post their sketches on a wall. Finally, each participant is given an equal number of stickers to identify their favorite features from everyone’s ideas.

Day 3, Converge. As a group, review the solutions from the previous day and take note of the most sticker-adorned features. Use these features to generate testable hypotheses (e.g. “implementing a text-to-speech feature will encourage less literate customers to better understand the terms and conditions”) and come to a consensus on which 3–5 features you’ll test.

Day 4, Prototype. The goal for this day is to do the least amount of work required to test a hypothesis. This may mean building a paper prototype, a rough-around-the-edges mobile app, or something in between like a Google Form or an AppSheet app; whatever is the shortest path to getting answers to your hypotheses.

Day 5, Test. Get out and visit the prospective users of the product or service and let them provide you with the answers to your questions, implications of your assumptions, and validation of your hypotheses. Repeat from step 1 as necessary.

Step 3. Producing Deliverables

Each of the testing approaches above can lead to a unique type of output, but each approach should accomplish the high-level goal of removing risk from the project. For example:

- Field Visits might lead to a journey map and/or service blueprint

- Data Jams might lead to a concise deck of insights drawn from the data

- Design Sprints can lead to a prototype, or a deep mapping of your targets’ needs, via the Lean FIBR Canvas, for example

With these outputs in hand, the team can decide whether (and how) to proceed with the product or service in question.

Limitations to the Nanoproject Approach

Realistically, there is no way that 1–2 weeks of work can fully mirror a larger pilot test. That said, through this small up-front investment, the expected value of the overall project is higher; an unsuccessful nanoproject is cheap, and success can provide critical validation around the most volatile and riskiest parts of the ventures.

Conclusion

Nanoprojects are a small investment with a huge payoff. They are a cost-minimizing way to give us the nudge we need to stay on the right path, or tell us quickly that no safe path exists to lead us where we’re trying to be.

“The journey of a thousand miles begins with one step.”

— Lao Tzu