Digital pathways to inclusive growth: BFA Global’s next generation of work in livelihoods

The new economy presents opportunities and risks for digital workers

Our excitement about digital platforms is grounded in their nature as enablers and accelerators of the digital economy. They have deepened last-mile access to markets by fostering digital payments, providing financing, and bringing operational efficiencies, better information, and transparency. They have the potential to go further to serve as marketplace intermediaries for the excluded populations which we ultimately aim to serve through our work at BFA Global. We see the potential generative power of platforms enables their users not only to consume but also produce goods and services which generate incomes and support new livelihoods. However, while these characteristics can be transformative, we acknowledge that the platform-led deconstruction of jobs into bundles of piecemeal tasks has also led to less agency and eliminated protections for formally employed workers.

There are already patterns and practices which give rise to concerns that earnings from gig work will always be volatile and under downward pressure from the global ‘race to the bottom’. Drivers on ride-sharing platforms continue to protest around the world, frustrated by meager wages and maltreatment. Clearly, the extent of downward pressure on rates of pay varies by the nature of the work–whether it must be locally provided (like taxi services) or can be globally procured (like many forms of pure online work). It will also depend on factors like whether the quality of tasks can be adequately verified, whether potential employers trust work records so as to be willing to pay more for experience and track record, and of course, on the market power which digital work platforms have to deduct their commissions, which average around 20% on major digital work platforms today, from some combination of seller commission and buyer fees (1). It is not unreasonable therefore to question if digital work can lead to large scale dignified and fulfilling work, when most of the power seems to rest with the platform.

Most people are not natural or successful entrepreneurs. According to the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, which has conducted large scale surveys for twenty years across numerous countries, the average total early-stage entrepreneurial activity rate across 48 countries is 12.6%, or around one in eight adults. Of the minority who are entrepreneurs, many are “accidental” and satisfied with growing to a certain size, and then subsisting off of the income. Many people would prefer a steady job instead of the risk and uncertainty of a business. But not every business has the capacity to grow, nor can every person be an entrepreneur or even desires to be one.

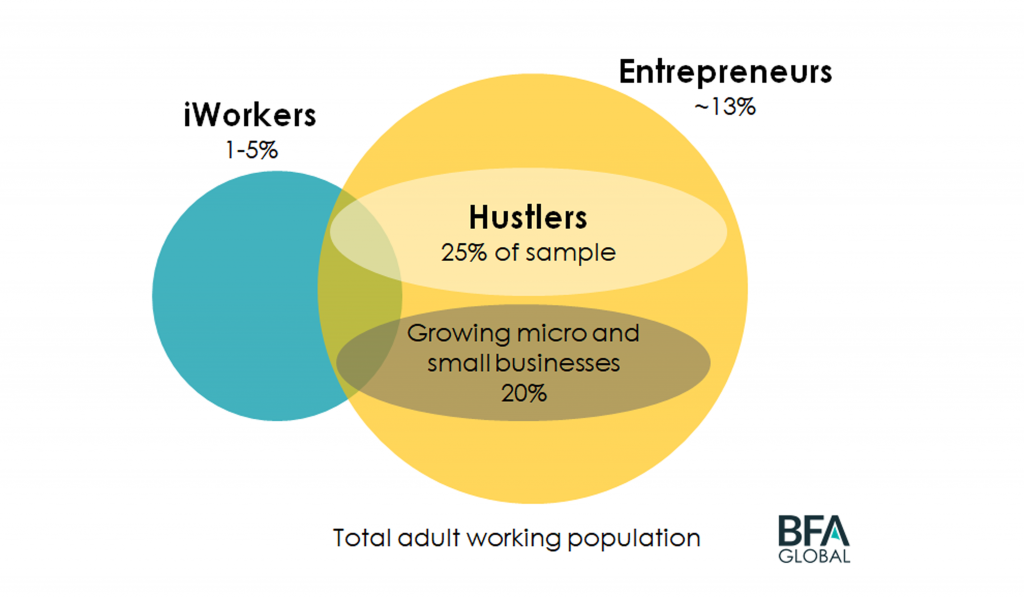

Currently, a relatively small fraction of all workers (1-5%) are what we term “iWorkers” whose livelihood depends on digital connectivity. Among these are “Hustlers”, persons with an internal motivation that drives them to strive and grow small ‘side hustles’ to become businesses. But hustlers are a minority of entrepreneurs–around 25% in our samples. iWork can support livelihoods for the larger group of non-hustlers too. In this blog, we will discuss the pathways for income growth for iWorkers and hustlers in turn based on our recent work in these.

Figure 1: Mapping types of workers’ means to livelihoods

iWorkers: Making a living through digital work

iWorkers are often called ‘gig workers’ since their livelihoods are built from a series of ‘gigs’ or ‘microtasks’, our broader definition includes online sellers and eLancers. The majority of iWorkers today are solo-entrepreneurs as a response to scarce formal employment opportunities. Many iWorkers may prefer the features of employment like steady income and income growth but are self-employed instead by need or circumstance.

A 2017 cross country survey by Research ICT Africa estimated that around 1% of African adults may already be gig workers today, although the measurements are still imprecise and estimates vary. However, the growth potential in this segment may be rapid. BCG has found that already higher proportions of people depend on gig work as a main source of income in middle-income emerging countries (5% of Brazilians, 8% of Indians and 12% of Chinese) than in higher-income markets such as US (4%). Widening the lens to those who do part-time gig work also increases the proportion of people working this way — by as much as 33% more in China for example.

As smartphone connectivity rises over the next decade, especially among the young, more and more workers will fall into the category of iWorkers. In our 2019 white paper on scenarios for digital commerce, we estimated that in Africa alone, up to 10% of the workforce (30 to 88 million people) entering the labor market over the next ten years may become iWorkers.

This week, we released the findings from the iWorker country diagnostic report for Ghana. The iWorker country diagnostic serves as a tool for policymakers, researchers, and private sector to assess the enabling environment for iWork to emerge; and it can identify policy actions to encourage positive outcomes from iWork. Listen to the webinar and download the report from our new iWorker website.

Hustlers: Informal microentrepreneurs at the start

Hustlers are those who start and run micro-businesses known as hustles. Some hustles are part-time (side hustles), others are full-time occupations. Many young adults start hustling out of necessity as there are simply insufficient jobs on offer to absorb the growing young population in Africa. Some hustlers succeed in generating the income levels they desire; many fail to do so and then as quickly move onto the next hustle. Some may be iWorkers in that their lines of work are dependent on digital connectivity.

Think of hustlers as microentrepreneurs at the very start of a venture. They have limited work experience, and are mostly active in informal and local markets. Very often, a hustler’s success or failure is determined by the support received during these formative years. Such support – capital and otherwise – is often contingent on a lender’s perceived potential for a hustler’s success as an entrepreneur. We have found in a range of interviews in East Africa that hustlers are increasingly using digital platforms (both social media and e-commerce) to find and even manage their hustles.

However, most have little experience, few assets to draw from, and no paper trail, so young men and women hustlers find the odds stacked against them when it comes to obtaining the right kind of support.

In the midst of the changing nature of work, workers needs are not being fully met

Unlike hustlers, the pathway to inclusive growth for most iWorkers is not mainly through more access to finance but through other pathways like greater income stability. Income stability could come in part through access to portable financial benefits that stay with the iWorker across platforms and which would help to smooth volatile incomes and provide cover against certain shocks to which they are exposed.

Financial instruments can go only so far, however; the growth pathway for iWorkers must include finding ways for more productive workers to distinguish themselves and be rewarded over time through higher earnings. These ways will include access to finance for appropriate training, likely delivered at least in part online to be affordable and accessible. But iWorkers also need reliable forms of reputation scoring based on their job performance. This should recognize good track records and distinguish for skills and experience. Today, most digital work rating systems are elementary and usually contain little signal value for potential buyers among the inconsistent noise. The systems may lack adequate recourse for workers who are unfairly rated downwards by spiteful or capricious customers. They certainly don’t allow for easy portability so that by leaving one digital platform, a worker may have to abandon the record of hundreds or thousands of completed tasks stored there: a risk which may give dominant platforms undue hold over workers.

We would like to see more efforts to investigate new ways of standardizing and combining these ‘reputation at work’ scores so that good work can be rewarded with higher effective wage rates and utilization rates. This will likely require a public-private effort, working with new data protection authorities, which are rapidly springing up to define portability of personal data in ways which covers workplaces; as well as with scoring providers who may develop the algorithms to extract a better signal from the complex noises here.

Implications for growing entrepreneurs into growing businesses

Propensity for success: Identifying entrepreneurs and matching with support

From among the many hustlers in the working population of emerging economies, how does one identify future enterprises that are poised to grow from a one-person venture to providing economic opportunities and employment for others too? Programs that provide loans or grants to individuals to start businesses without considering the inherent propensity to entrepreneurship often end up being exercises in futility. Instead, focusing on financial investments on growing businesses with a greater likelihood of success would yield higher returns. But how can we know who is more likely to be an entrepreneur and to succeed in a business venture ex-ante?

Just under half (44%) of young people surveyed in our research with Kenyan media company Shujaaz Inc. self-described themselves as hustlers. Of these, just over half noted that their hustle allowed them to be financially independent. We have developed a “propensity to succeed as an entrepreneur” score based on conversational content in their social media, complemented by parsimonious SMS surveys that signaled a higher propensity to be a successful hustler based on words and themes they used.

The propensity score we developed identified these successful entrepreneurs ex-ante two-thirds of the time. In addition, the score provided an ex-ante lift of about five times – that is, the highest likelihood of success seen was about 55%, while the lowest was 10%. With the right support, hustlers who score highly may expand their hustles to become micro and then small businesses, which then employ others. This is an example of a pathway to inclusive growth – identifying at an early stage hustlers who are more likely to succeed so as to match these high potential entrepreneurs with the appropriate resourcing.

Unlocking micro and small enterprise financing constraints with digital solutions

Some micro and small enterprises already employ people who rely on digital means to perform their work. Digital platforms which can observe and authenticate sales activities first hand may be better placed to provide business financing than traditional financiers who cannot observe sales patterns reliably or in real-time. This difference has been on part of the success story of Chinese e-commerce, where giant platforms like Taobao also offer microfinancing to entrepreneurs through platforms operated by affiliate Ant Financial. Groups of growing micro and small enterprises have thrived in geographic clusters called Taobao villages, and have become significant providers of new employment.

Our most recent research with digital commerce platforms Lynk (blog forthcoming by FSD Kenya) and Sokowatch provide further examples of a platform offering asset-based financing for productive tools and a merchant app offering in-kind credit respectively, to overcome working capital constraints. These tailored solutions have allowed informal artisans and merchants alike to maintain stock and cash flow, invest in their businesses, improve efficiency and quality of performance, which are all critical factors to master on the way to growth.

Getting to inclusive growth: the challenge ahead for workers and for firms

So we see two pathways to inclusive growth. First, our work around iWorkers aims to support portable benefits which can improve their financial health, and to catalyze experimentation with different ways of rating digital work. The pathway to inclusive growth through enhanced digital work is complex. Global understanding is still at an early stage. By contrast, the second area, hustlers, as well as micro and small enterprises more generally, are a better established concept. But here we aim to support better matching of entrepreneurs with potential with appropriate earlier stage support. Better matching will strengthen the long-identified but often weak-in-practice entrepreneurial pathway to inclusive growth.

We expect that the hustlers, including iWorkers, who break away and succeed in attaining larger scale will end up among categories such as Mastercard’s growing micro and small enterprise called Strivers and ANDE’s small and growing businesses. The success of growth-oriented hustlers will contribute tangibly to inclusive growth in household income of the owners, and also in job creation for others. Firms that grow to become small and medium enterprises (SMEs) contribute 45% of total employment and 33% of GDP in emerging markets. Indeed, enterprises in developing countries that employ 5 and 99 employees contribute to 50% of net job creation.

We hope that by experimenting and prototyping these pathways for both iWorkers and hustlers, BFA Global’s work can contribute to better livelihoods for the wide spectrum of workers we see in developing economies. We look forward to working with our partners towards helping to shape a new world of work in the 21st century which is more inclusive and equitable for all, and especially in developing markets.

Learn more at www.bfaglobal.com and @BFAGlobal and follow our upcoming blog series on iWorkers, hustlers, livelihoods, and the digital economy.

(1) Visit bfaglobal.com for a new BFA Global Briefing Note on labor platforms, publication forthcoming.