A bridge too far? Paying for school in an economic crisis

Originally posted on the FSD Kenya Website, November 18, 2020

Parents across Kenya are receiving ambiguous messages about the timing of school re-openings amid the coronavirus outbreak. While parents are eager for their secondary school children, in particular, to get back in the classroom, few low-income Kenyans have a plan for how they will pay, considering their depleted resources and the level of debt they have taken on during the COVID pandemic.

Education disrupted

Like many around the world, schools in Kenya closed their doors in mid-March as coronavirus arrived in the country, and immediate steps were taken to curtail its spread. Children in more expensive private schools shifted to online learning. While some educational programming was broadcast on television and radio, the lower-income majority of learners were left on their own, often without much access to computers, data bundles, or costly print outs of exercises distributed by teachers.

Some parents stretched to pay for private tutors and lessons, but children had lots of extra free time on their hands. By September, participants in the COVID Diaries had become very concerned about the social consequences of having children out of school for so long. Jenifer’s 16-year-old daughter, for example, had become pregnant and had already attempted an unsafe abortion. Mary, a village elder in Vihiga, lamented several cases of early pregnancy in her area as well, as Evans, a community worker in Mombasa also worried about young men getting into drugs and alcohol. Universally, parents expressed their eagerness for young people to return to school, and all of them were adamant that their children would return as soon as they were allowed.

When exactly that will happen is unclear. In July, the government announced schools would remain closed until January. In September, the government sent out mixed messages hinting that perhaps schools would resume sooner. In early October certain students (class 4, class 8 and Form 4) were called back to classes. But, as of this writing, a planned expansion to other students has been put on hold amid rising COVID cases.

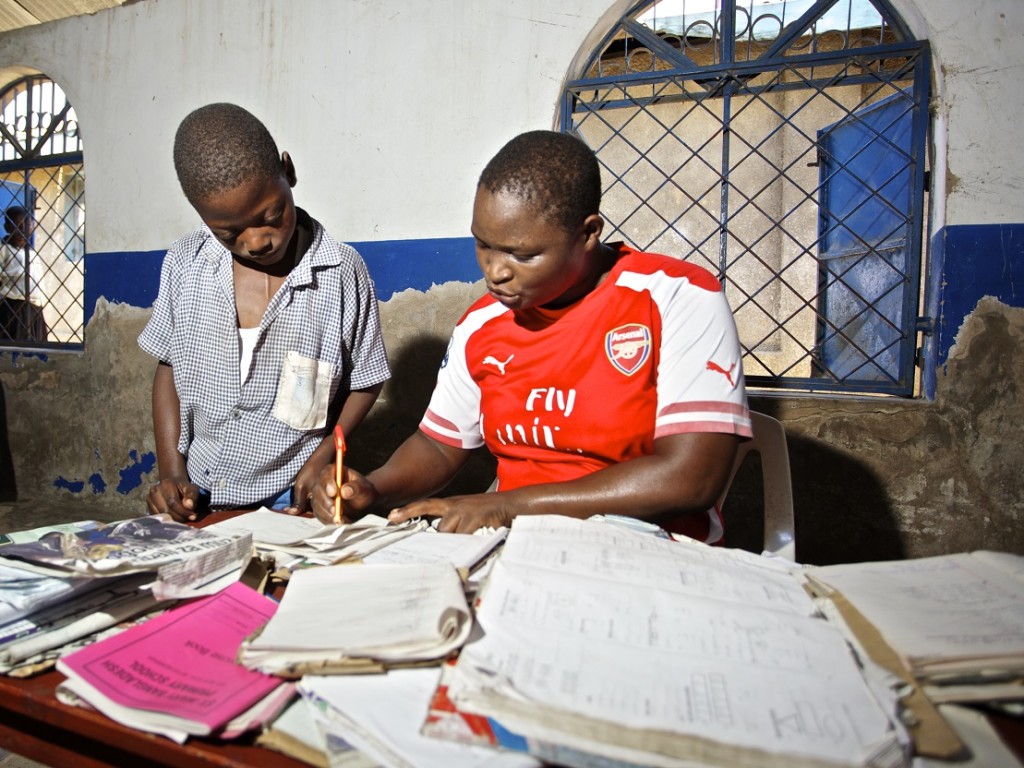

The costs of education

The trouble is that school fees are very expensive, particularly for secondary school, even at public day schools. The out-of-pocket costs for a year of secondary day school start at around Kshs 20,000 and go up from there. Right now, the median household in our sample is only bringing in about Kshs 4,000 per month. Some families already paid for fees and don’t have much to fear right now, but many others also have outstanding debts to their children’s schools. As schools reopen, they will need to find both money for the new term and money to clear old debts with schools, which stand at an average of about Kshs8,000 (median Kshs3,000) for those who already have school fee arrears.

Depleted assets

And they will need to find this money in spite of their assets—as well as the income and assets of their social networks—being depleted through the protracted economic contraction caused by COVID-19. For example, Carol in Mombasa saved KES 5000 in M-Shwari for the next school fees payment for her older kids. But, when the virus arrived, she lost many of her hair plaiting clients and has used all of that money for food. Angus, a farmer and mason, saved up KES 20,000 in his M-Shwari Lock account for school fees, but as his income dipped, he had to tap into this money to buy medication when his wife became sick. Not only has monetary savings been depleted, but many families have sold off liquid assets like chickens, goats and cows, and a number have even had to sell off personal belongings such as clothing, furniture, and gas canisters just to survive.

Remittances had also slowed through June of this year as extended family members lost their incomes. Some of that has come back, but many are still earning less from both their formal jobs and their businesses than before COVID.

And lines of credit are, for many, maxed out. Emmah in Vihiga explained, “I don’t have money to pay school fees, especially if they are to go back this year. Usually I borrow from M-shwari, but I already owe them.”

For Ellen, a single mother in a small Rift Valley town, it’s not even about lost assets, but lost income and existing debts. When COVID-19 hit, her shifts at a local club were cut from six days a week to two. She struggled to pay rent and sent her son upcountry to reduce costs until she could stabilize. As she looks ahead to schools reopening, she says she has no idea how she will manage. “I still have last year’s arrears to pay. I already owe the school KES 24,000, and I know they will ask me to pay fees for the subsequent terms.”

With all of these constraints, coming up with school fees to keep their kids back in school once they fully reopen is set to be a major challenge. Education Cabinet Secretary George Magoha has said learners should be admitted even if parents cannot pay fees, but parents are skeptical their local schools will follow suit. Some private schools have permanently closed, unable to stay in business through the COVID period.

The trouble with uncertainty

The lingering uncertainty of when schools will reopen is having important effects not just on parents, but also on local economies. Parents are starting to save, but doing so often pulls money out of its “active” uses generating returns through chamas and businesses. Businesses are also feeling the pinch from customers who are cutting back on purchases as they brace themselves for coming school fees payments. As one merchant told us, “I see my sales go down. Parents are starting to spend less and get ready for schools to open again.”