Corona Case Studies: Should I stay, or should I go?

Originally posted on the FSD Kenya Website, April 14, 2020

Considering urban to rural migration as urban incomes dwindle

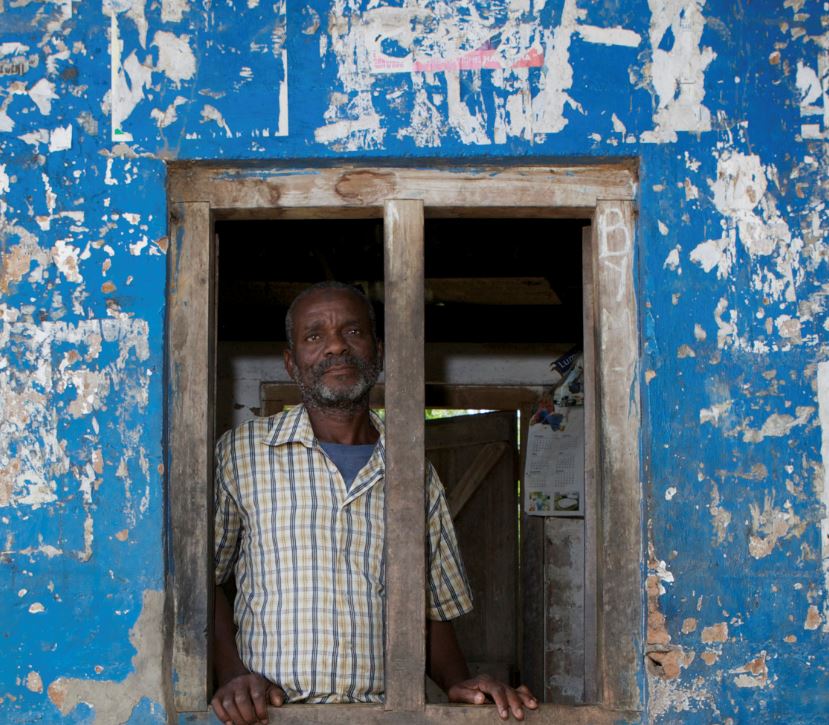

Collins, 75, once an ambitious, savvy businessman in Kariobangi, is now coasting through the end of his years. “Things are not really improving, not really getting worse. I’m an old man now. I’m zero grazing.” He no longer has the pressure of school fees to pay, so he feels like he can relax a bit and just be comfortable with what he has. He can get by for a month on just about Ksh 5,000 ($50) and tries to send his wife upcountry about Ksh 5,000 ($50) as well.

Some days he wonders if all of his struggles to maximize earnings were worth it. After putting his daughter through secondary school, she got married as soon as she finished. His grandson at Maseno University graduated but has no prospects for work. It all feels a bit anticlimactic after a lifetime of hard work.

Given that his days of pushing himself to grow his business and multiply his investments through more than half a dozen chamas (savings and credit groups) are over, he felt that if things got bad, he could just go home to Nyeri. “I have a big farm there, with dairy cows, and we have plenty of food.” He thought he would retire at his rural home, but changed his mind. “I feel like I’ve just stagnated the past three years. I haven’t done any new developments. But I have a feeling that if I had gone to the village, I would be dead by now from overthinking.”

As coronavirus takes hold in Kenya, he was finally thinking about going home. One concern for him was his health. “The virus itself is scaring me! I’m old. If I get that thing, I probably won’t survive.” But he was also nervous about the risk of potential rising crime as unemployed people became increasingly desperate. He’s also lonely and a little bored when he has to be inside the house by dark. He says he can no longer entertain himself by reading the newspapers or watching TV because of failing eyesight. And, perhaps most importantly, he wasn’t sure if he could keep his business alive. Then what would be the point of staying in the city?

Business had dropped for everyone in the area, including him. “It’s funny, actually. Everyone is crying over this thing while lazing around. Even the idlers are claiming that they can’t do any work now, because of corona.” Two weeks after coronavirus came to Kenya, he was still running his business selling mutura (a kind of sausage) and firewood, but sales had dropped. With the curfew, he’s missing out on clients who used to buy mutura leaving their favourite drinking spots. He has nowhere to refrigerate leftovers, so they go to waste. He hasn’t been paying his supplier, who has also been hard hit. The supplier sold mutura ingredients from a stall in Kiamaiko market, which had been closed down by the government to enforce greater distancing measures.

Last week he was already working to get some finances lined up to get himself through this period. He had a loan limit of Ksh 9,200 ($92) on M-Shwari and Ksh 34,000 ($340) on KCB M-Pesa. Just before we spoke with him, he had quickly repaid an M-Shwari loan so he could borrow Ksh 9,000 ($90) again. He borrowed immediately and sent his wife Ksh 5000 ($50) so she could stock up on essentials.

He had savings in his chamas, but right now could only access it through a loan. He requested loans in two groups, but it was difficult to negotiate with the officials since the groups weren’t meeting in person. Technically, loan approvals were only meant to be done in group meetings. Still, he was worried about having all his savings in the group, out in loans to other people while the situation grew increasingly destabilised. He was hoping that some healthy chunk of the money would be with him, in the form of a loan. He requested his share-based limit, Ksh 50,000 ($500).

He called us yesterday to let us know they lent him Ksh 30,000 ($300), significantly less than he would normally be allowed, but still something. He sent Ksh 10,000 ($100) to his wife already to buy animal feed for the dairy cows. His daughters in Nairobi were feeling more pinched by now as well. One had been making a living washing clothes for others, but no one wanted outsiders in their home right now. The other had a small kiosk and her business has nearly collapsed. The two sent their children to ask their granddad for money. He gave them each some of the money from this loan.

It looks as if that loan will have to last him several weeks. As of yesterday, he has stopped selling mutura completely and is only selling the firewood in small amounts to a handful of clients.

And his backup strategy of going to his rural home has now vanished. Residents of greater Nairobi can no longer travel upcountry. The presidential order took immediate effect, leaving him stuck to wait out the crisis alone.

This is part of a series of rapidly-produced blogs on how low-income Kenyans are coping with the changes in their lives induced by the novel Coronavirus (COVID-19). This research was implemented in partnership between BFA Global and FSD Kenya. Read more about the Kenya Financial Diaries project here. We will continue checking in with Diaries participants throughout the crisis. For the latest news and insights from this work, follow @FSDKe and @BFAGlobal on Twitter, as well as hashtags #Covid19DiariesKenya and #KomeshaCorona.