Digital financial transfers can supercharge the response to COVID-19

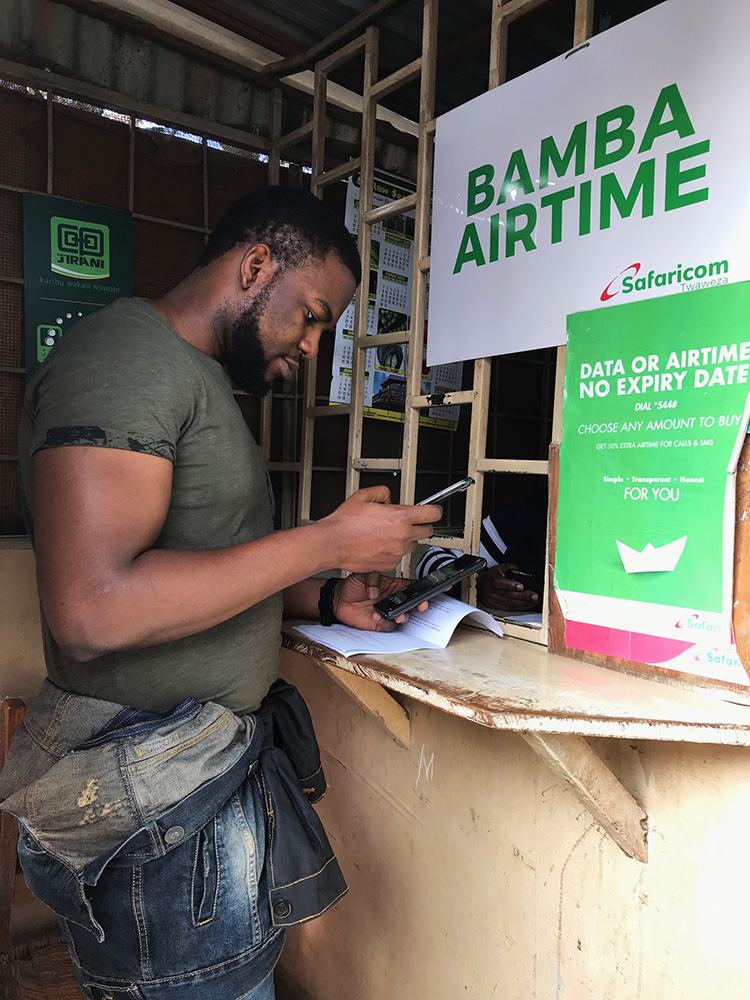

As soon as the scale of the worldwide pandemic became apparent, the Kenya government swung into action with measures that are increasingly familiar around the world: encouraging social distancing, suspending travel, closing schools, etc. But, the Kenya government had an additional weapon in its arsenal: encouraging people to use cashless transactions to prevent transmission via the physical handling of money and digital finance.

Since then, the Kenyan government has doubled down on encouraging digital finance: first, by negotiating with banks and mobile money operators to eliminate fees on smaller transactions (those under $10, but some have eliminated fees on larger amounts as well), and second, by requiring cash itself to be quarantined for a week before being recirculated by banks.

The private sector has embraced the idea that we should stop using cash – my texts and emails are full of appeals to avoid the banking hall, the payment queue, and the checkout line by using digital payments and, in particular, Kenya’s ubiquitous payment platform, M-Pesa. When I was at the supermarket yesterday, we all adopted this attitude and glared at the family paying for a full cart with a pile of crumpled, dirty bills.

It doesn’t stop there: now the Government is encouraging banks to give borrowers up to a year to repay their loans, including digital loans that typically have a 30-to-60-day repayment period. Next, the Health Cabinet Secretary has said that nobody will be cut off if they don’t pay their water bill. Meanwhile, there’s a social media campaign for landlords to forgo rent while the crisis lasts. I initially thought this was all bonkers, but I now see the suspension of repayments and interest in the UK and US for mortgages and student loans.

I find two things peculiar about this overall approach to debt and banking services:

1. First, why are we expecting the private sector (including private individuals like landlords) to bear the cost of the crisis when their peers in other countries are receiving support directly from the government? Not only does this push social costs to the private sector, the benefits are accrued unevenly: people who have an outstanding loan get help, but those who have only savings get none.

2. Second, for Kenya in particular, why have relief payments (delivered via the digital financial services infrastructure) not been a priority? Kenya is a lower-middle-income country where 85% of the population works in the informal sector. In the Kenya Financial Diaries, we found that people have savings for about 30 days of expenses on average (far more than in Mexico, or India, or the US), but those reserves will quickly get exhausted if social distancing lasts for much longer (as is expected) or a full lockdown comes into force (which is on the table).

To truly capitalize on Kenya’s unique digital financial infrastructure to help people weather the crisis and recover from it so as to protect families and the economy, the Kenya Government needs to institute direct cash transfers to every adult as an immediate priority.

BFA Global’s Financial Diaries research has also shown that comparatively small amounts of money can make a huge difference to a family in crisis and that people need surprisingly little capital to be able to get on their feet again after a disaster. Amounts of Kshs 2,000-5,000 (US$20-$50) would constitute meaningful support in this difficult time, and could prevent people from needing to break the curfew to seek an income.

Unlike other countries, a digital relief payment would be easy to implement in Kenya and could immediately reach 83% of all adults through existing mobile money accounts. We already have digitized social transfer programs that include an additional 5 -10% of the most vulnerable population, which could be a complementary channel for transfers. The 5 -10% of the population could be supported manually; this is a small and potentially manageable share of the population.

I am sure a digital distribution system would not be perfect, but we can learn from past experiences like the emergency response in Haiti and efforts to support the refugee population in the region. From these experiences we know that the lack of existing digital infrastructure is a major impediment to responding quickly in a crisis, but Kenya’s digital infrastructure is widespread and heavily used so we may have more success. Still, it is to be expected that there would be some overlaps in SIM registrations as well as some gaps, and that some people who are not really deserving or distressed might receive the transfers. However, with the exponential pace of the epidemic, these might be costs we should bear in exchange for instantaneous support to ~90% of the citizens who are currently anxious, resource-strapped, and without clear prospects for earning a livelihood while they stay at a social distance.