Digital Savings Groups Can Help Women Finally Bridge the Financial Gender Gap

Authored by Sushmita Meka; Sally Ross, AKF; Daryl Collins

The rapid growth of mobile money in some countries has hastened the digitization of financial management for many people on low incomes but seems to be leaving women behind. Recent evidence from the 2017 World Bank Global Findex database shows that only 37 percent of women in developing countries have some sort of financial account compared to 46 percent of men — a financial access gender gap that has stubbornly persisted since 2011. Likewise, there is a persistent gender gap in access to digital technologies like the internet — the World Wide Web Foundation suggests that women in urban areas of developing countries are a full 50% less likely to have access to the internet than men. These two factors reinforce the difficulties that low income women have to Improve their own economic welfare and that of their families.

BFA, Aga Khan Foundation (AKF), Financial Sector Deepening Trust Tanzania (FSDT), and Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation have taken the view that the key to closing both gaps may be found in savings groups, which are highly effective and popular, particularly among women. Informal savings groups are used in nearly every developing country in the world and several developed countries as well. As one woman told us with utter seriousness, “We would die without our savings groups.” Non-government organizations (NGOs) promote a slightly more complex version of savings groups that enable borrowing as well as savings, affording members the opportunity to purchase assets and gradually grow their businesses.

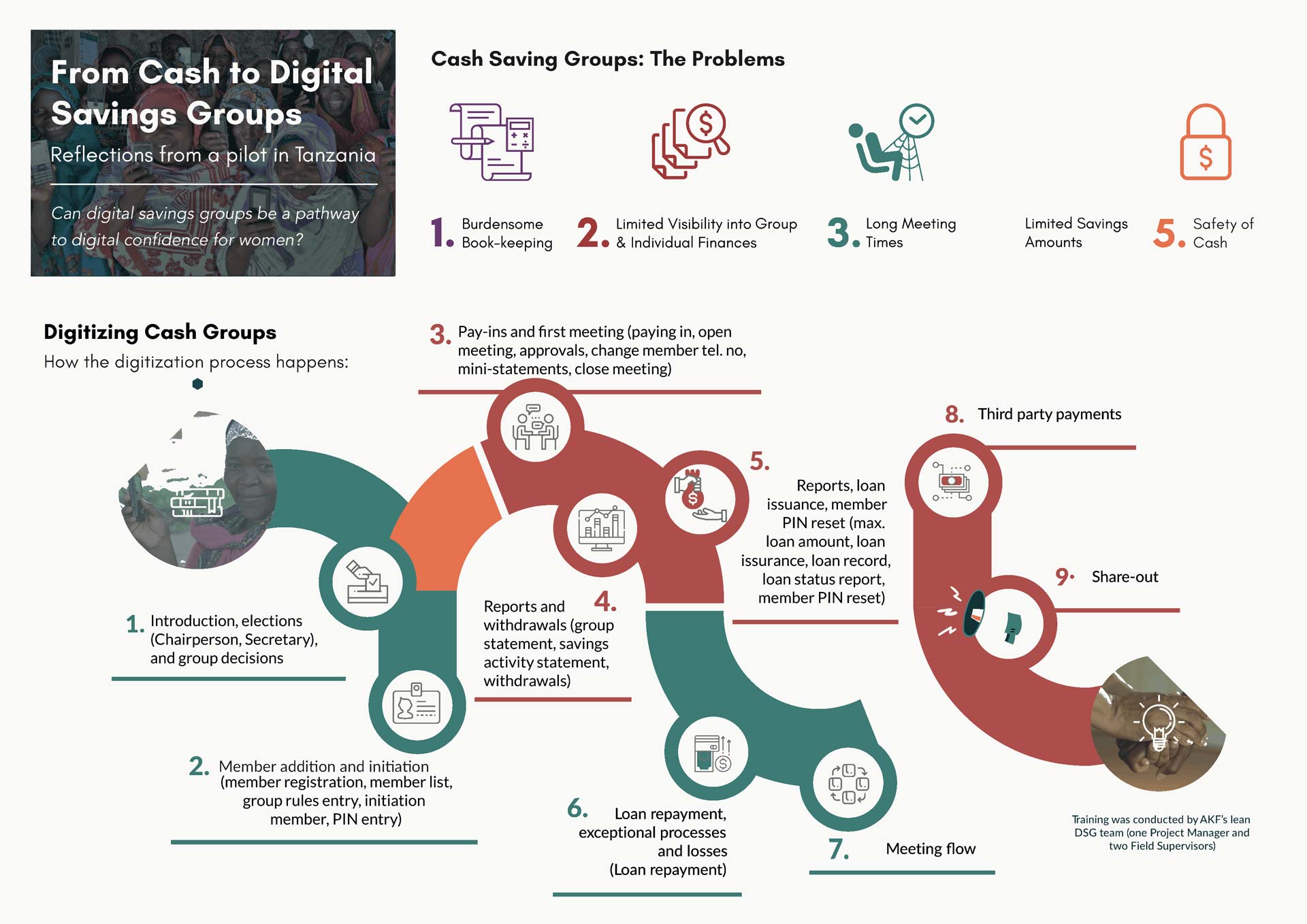

However, most savings groups are cash-based, which makes their weekly meetings lengthy and, well, a bit boring. While the secretary and cash-handlers painfully count out stacks of cash and make copious hand-written notes in the group notebook, the two dozen other members stuffed into the small room sigh in exasperation and try to stay awake. And members are justifiably worried about the risks of holding large amounts of cash; between 2012 and 2015, for example, AKF-organized groups reported 75 cases of theft.

But if these groups were to use cash alternatives, they could well provide the bridge needed to help women across the digital divide. Not only are savings groups emotionally and financially important to women, but they also entail a range of different types of transactions: paying in, getting paid out, and checking balances. By digitizing their savings groups, they can go beyond simple cash transactions to a range of new functions that can help them overcome other challenges, all while learning in a safe and welcoming forum.

The promise of digitized savings groups (DSGs) drove AKF to design and build a specialized platform with the help of Tanzanian payment aggregator, Selcom. Over the past year, AKF, with the assistance of BFA, ran a randomized control trial to determine whether digitized savings groups helped women cross the digital divide. Our findings from one cycle are promising and suggest ways to increase effectiveness in the future:

The Switch to Digital is Challenging…

A significant number of members were apprehensive about the DSG platform and worried about the safety of their money, so they “sat out” the cycle. Those randomly allocated to the digital group had higher turnover; 35 percent stepped aside for the digital savings group cycle compared with only 17 percent for the cash savings groups.

Training matters; by the end of the cycle, most members that stayed had more confidence using the platform.

As hoped, members helped one another learn how to use the platform, although not enough to enable members to perform transactions by themselves. Mid-cycle, AKF went through an extra round of training and providing how-to materials for the digital groups, and those efforts made a difference. By the second half of the cycle, 74 percent of DSG members surveyed said they were confident about sending deposits to the platform on their own.

The share-out was a critical moment in solidifying trust.

The sharing of saved funds at the end of the cycle convinced members to rejoin digital savings groups after opting out of the first cycle. One member explained her change of heart: “I only trusted the group partially before, and then I dropped out since I was afraid my money would be stolen. But now, after seeing how the share-out came about for the members, I am very interested…I fully trust the digital group now.”

…But the Benefits Are Obvious

Digital savings groups improved the perceived safety of funds.

Cash savings groups used a physical lock-box, group members viewed as insecure. More than half of the returning members cited safety as a key reason why they were willing to try the digital savings groups and 97% of those staying in the group felt that storing money in the digital platform is safer than in a lockbox. Hamsa, a former secretary in charge of holding onto a cash lockbox, described the weight of responsibility that she carried in previous cycles: “There really is no peace when you are in charge of keeping the box. One can barely sleep at night as there is constant fear of your house being broken into and robbed, sometimes even by armed robbers.”

Digital groups saved members time and trouble.

The cash group secretaries needed to count and dole out cash as well as perform paper-based bookkeeping, making cash savings groups a stupefying, hour-long ordeal. This was particularly true of share-out meetings, which could take around three hours due to the need to physically count and calculate how much cash each member was owed. DSGs took less time.

And Members Grew More Confident in Using Digital Technology

Being in the digital savings group increased ease of use of mobile phones.

Knowledge of how to send and receive text messages increased among digital savings group members following the pilot (growth of nine and six percentage-point increases, respectively), and members felt it was easier to do both. DSG members needed to access a USSD (Unstructured Supplementary Service Data — i.e. quick codes used on a feature phone to communicate with a mobile network provider’s computers) menu to navigate the digital platform. This practice appears to have increased user comfort with both sending and receiving text messages independent of the platform.

Favorable perception of mobile money grew more among members of the digital savings groups.

More digital group members felt that mobile money was easy to use (a 17 percentage-point increase over cash groups) and were slightly more likely to use mobile money to store money than those using cash groups. Moreover, there was a significant increase in the perception that mobile money charges are fair among digital group participants.0

After their experiences with the digital savings group, 89 percent of those who participated said they wanted to use the platform again on the next round — a ringing endorsement of the digital group and the benefits members felt it offered them. Moreover, of those that left the group early, 34 percent said that they would join a digital group after watching and hearing about the members who went through the digital savings group cycle.

The financial gender gap in part reflects another gap — the digital divide between those who are comfortable with technology and those who are not. For rural people on low incomes, there is a steep learning curve in adapting to digital technology. However, the AKF experiment with digital savings groups suggests a way of closing both the financial gender gap and the digital divide simultaneously. Our experiment with digital savings groups shows many are willing to climb the learning curve and cross both for a purpose they consider fundamental to their survival.