Potential for Mobile Money in Vietnam

Co-authored with Ashirul Amin & Laura Cojocaru

Early adopters in Ho Chi Minh City embrace payments but mobile money has yet to gain ground

Just one year after launching its mobile wallet and payment app, Vietnamese FinTech company Momo boasts that the app has one million users to add to the 2.5 million mobile money customers Momo had announced in 2016. While preliminary research suggests that these mobile money customers are young, urban men paying for goods and services, BFA is staking a closer look at usage patterns to help a local microfinance bank identify opportunities deploy mobile money among its customer base.

Microfinance banks like the Capital Aid Fund for the Employment of the Poor (CEP) hope to use mobile money platforms for digital payments and savings to lower costs and offer clients greater convenience to better serve the un and under-banked communities that make up two-thirds of Vietnam’s population.[1] .

As part of the OPTIX project, sponsored by MetLife Foundation, BFA spoke with 315 mobile money users in Ho Chi Minh City, where CEP operates.[2] These conversations suggest that CEP will need to invest in facilitating enrollment and access through expanded agent networks to effectively deploy mobile money. While such infrastructure and logical challenges exist, Vietnam has advantages relative to other mobile money markets because providers capitalize on the existing perception that mobile money is used to pay for goods and services, like banking services.

Challenge: Getting Signed up

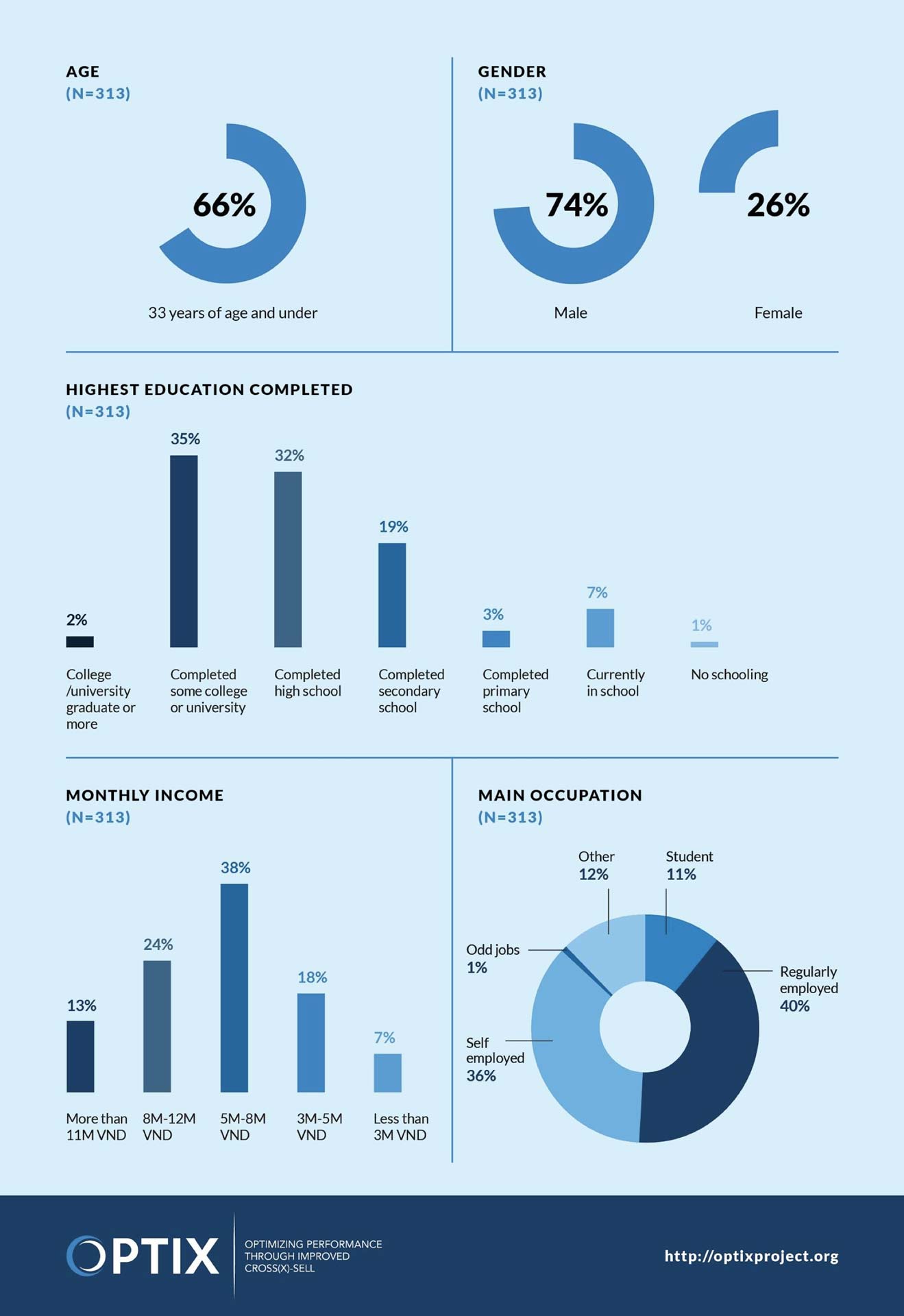

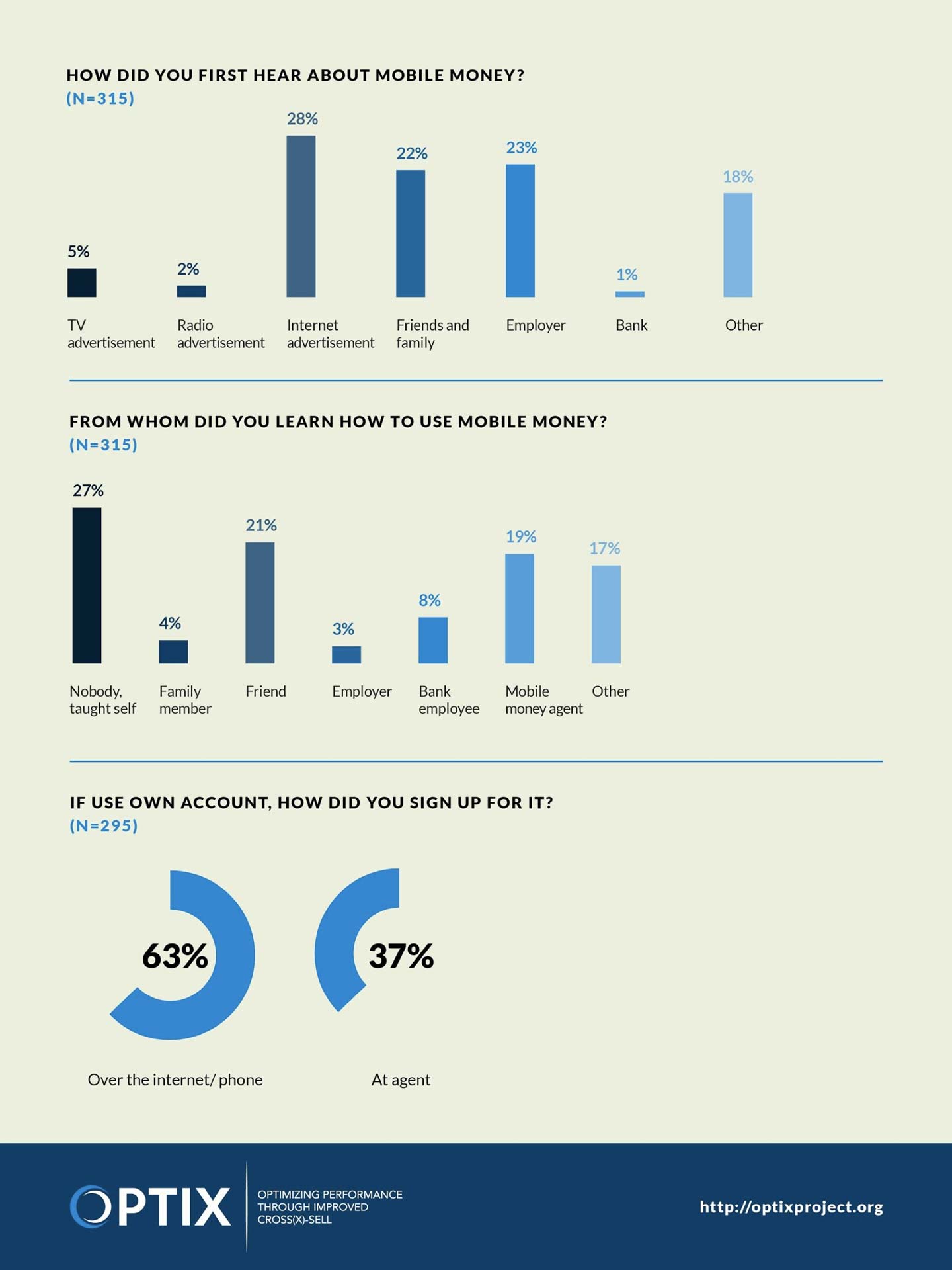

Our interviews suggest that most mobile money users consider themselves to be “tech-savvy” with 98 percent noting that they “like to try new technology”. This likely reflects the fact that our respondents tended to be young (33 and under), male, and economically well-off (75 percent of the respondents earned a monthly income over 5 million VND as compared to an urban average of~3.9 million VND or 172 USD).[3] Most (63%) signed up for mobile money via their phones or the internet, rather than over the counter through an agent.

However, for CEP, microfinance clients are different from our respondents in important ways. Whereas respondents were evenly divided between self-employed and employed, a higher proportion of people are self-employed in Vietnam and among microfinance clients (in 2014, 36 percent of total employment was wage employment[4]). Furthermore, most microfinance clients are women living in rural areas. Lessons from other mobile money markets suggest that this base will depend on agents to learn about and then utilize mobile money services, unlike our respondents.

For CEP, tapping into a broad, well-distributed agent network will likely be important to deploying mobile money among their customers. However, such networks are still limited in Vietnam. Momo has only 4,500 agents in place and BFA found that only one in three CEP clients are even aware of Momo, Payoo, or other mobile wallet services.

Opportunity: E-Wallet Usage and Satisfaction

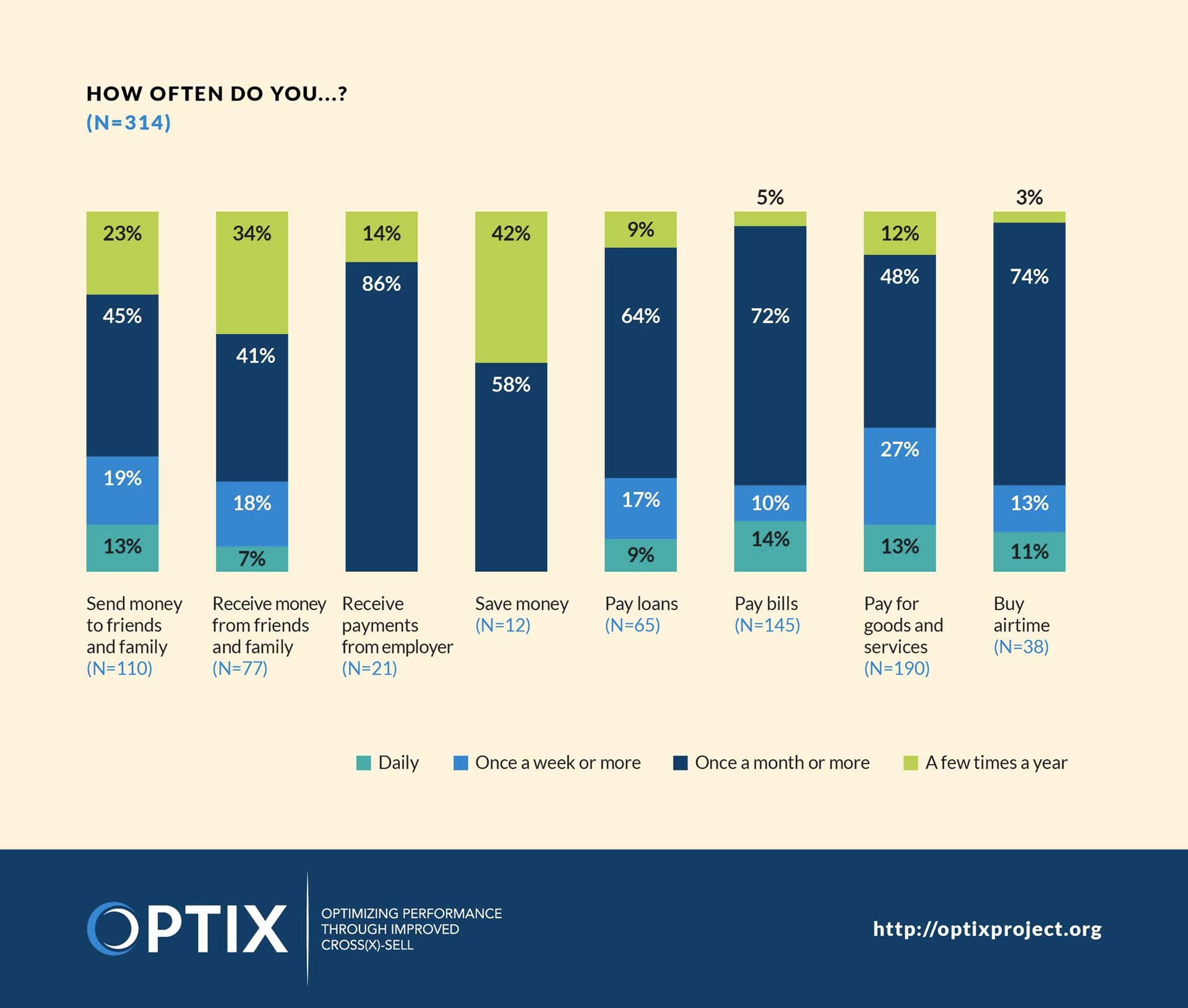

Since current mobile money customers primarily use the service to pay for goods and services, digital repayments to banks will likely fit with how people already understand the service. Sixty percent of respondents reported using mobile money to buy goods and services, followed by 46 percent using it to pay bills. This is an advantage vis-a-vis other emerging markets where the dominant use case for mobile money has been person-to-person transfers and remittances.[5]

While the case for loan repayments may be easy, the case for saving through mobile money may be more difficult. Mobile money is still perceived primarily as a payment tool and not as a store of value for the longer-term. And respondents kept small but not insignificant amounts of money in their mobile wallets, but they did not perceive them as “savings”. Mobile wallets can provide the unbanked with a secure place to save (versus under the mattress) and could allow them to send money outside of work hours to family in other cities. These are important capabilities because using mobile money to save and make remittances has knock-on long-term benefits for poverty reduction.[6]

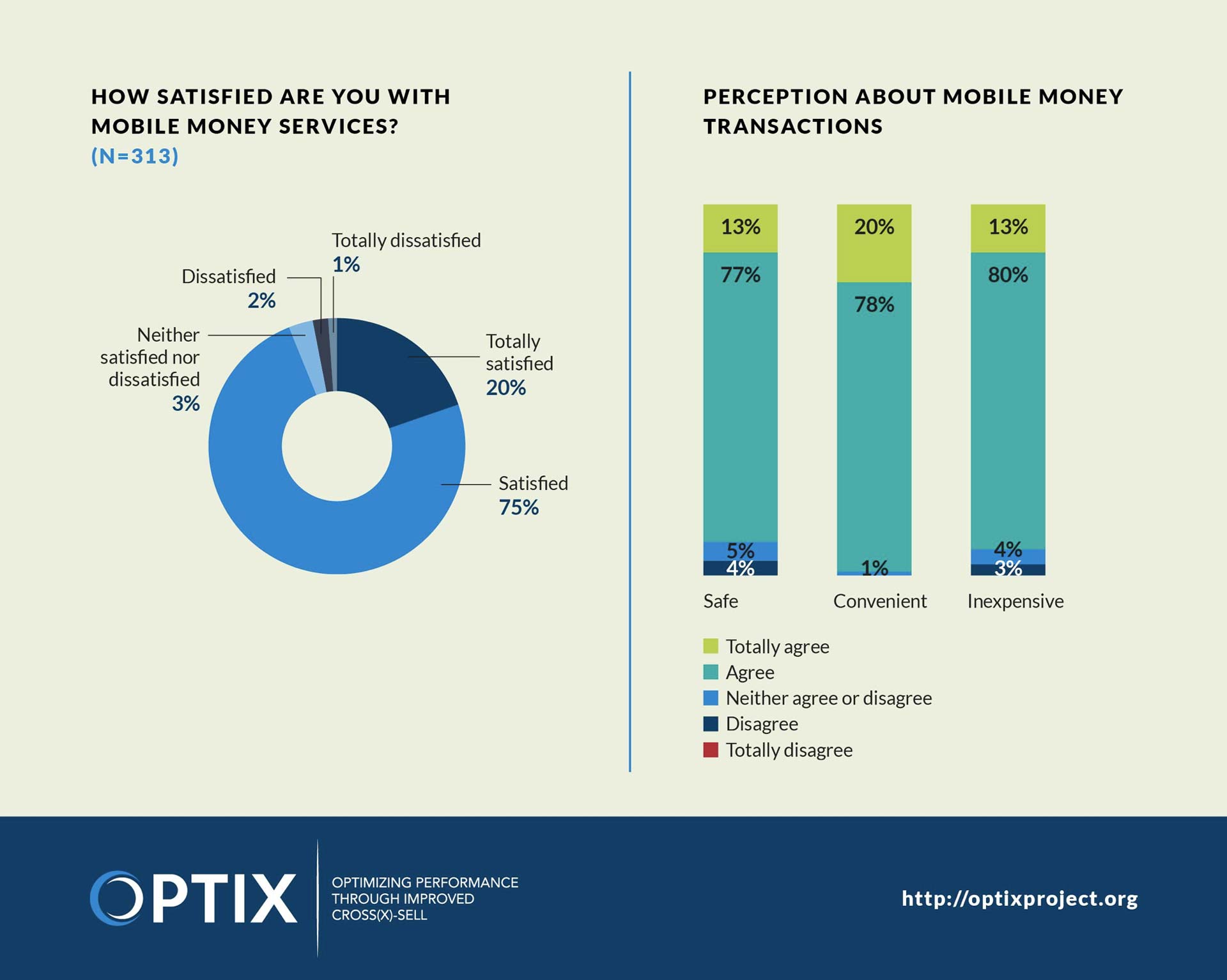

Another promising finding are the high rates of satisfaction reported by current users. 95 percent of respondents reported being satisfied with mobile money; it was perceived as a safe, convenient and inexpensive way to conduct transactions. While, respondents reported facing issues related to network outage (50 percent), long wait times with agents (36 percent), lack of digital (25 percent) vs cash money (11 percent) to service clients’ needs and unhelpful customer care (17 percent),only 3 percent encountered fraudulent activities.

Implications for CEP’s Microfinance Offerings

Ultimately, mobile banking is a promising avenue for Vietnamese microfinance banks with the potential to make transactions safer, quicker, more transparent, and cheaper for both clients and the bank itself. In addition, the timing for mobile banking seems right: Vietnam boasts one of the highest rates of smartphone usage in ASEAN at 29% and the government recently announced that it will push to become a cashless economy by 2020.[7]

Additional effort will be needed to make mobile money relevant to CEP’s customers and a worthwhile financial investment for the institution, but armed with the knowledge that mobile money could be a promising channel, CEP is now at the drawing board crafting an appropriate digital microcredit loan product. Stay tuned!