Stories of Climate Change and Resilience

As the world increasingly turns its attention towards making progress on climate change, stakeholders must ensure that the voices of vulnerable populations are not lost. Although poor people are the most affected by climate change, they are unlikely to be represented in the global forums and discourse, like the World Economic Forum or the upcoming COP26 conference, where climate change policies are set.

Farmers, fishers, foresters, herders, and the urban poor — will bear the brunt of climate change impacts. UNFCCC explains that the poorest, and those who depend on a healthy natural environment, are the most at risk. For example, forests support more than 1 billion people living in poverty and 80% of the world’s extreme poor live in rural areas and depend on agriculture for their livelihood. As temperatures rise and rainfall is less predictable, these people stand to lose the most. Furthermore, FAO adds that these populations are more likely to live in high-risk geographical locations, and have limited ability to cope with climate hazards due to “low incomes, lack of savings, weaker social networks, and low asset bases”.

To spotlight the voices of affected people, the DF4CR task force commissioned primary research among climate-vulnerable populations. The findings will be published next month; our hope is this effort helps to remedy their exclusion from global fora.

The goal of the research was to elevate the voices and perspectives of vulnerable people by connecting their expressed experiences and worries with climate change vocabulary and narratives. We completed a mix of qualitative and quantitative research with climate vulnerable rural and coastal communities in Mexico, Nigeria, and South Africa, focused on three key questions:

- How do vulnerable populations understand climate change, including both extreme weather and long-run changes in climatic conditions? Do they account for climate change in their daily decision making or long-term planning?

- How have climate change hazards affected these populations to date? What products and services are they already using to manage these impacts, if any?

- How have planning and ambitions for their future changed because of climate change impacts? Have they made any investments or adjustments to livelihoods and assets based on understanding or experienced hazards?

Research in urban settings was not completed as a part of this work.

RURAL EXPERIENCES

3.4 billion people globally live in rural areas, including more than 70% of the world’s poor.

Nearly all people living in rural areas, most of them poor, depend on farming for their livelihood and a large portion of household food consumption.

Changes in weather patterns, such as the duration, timing, and intensity of rainfall, impact the farming productivity and availability of natural resources. The projected impact of such changes on agricultural yields varies by crop and regions, but could be extremely high; for example, climate change could drive 60% lower productivity for staple crops like maize in Latin America and Africa. These weather changes also impact the prevalence of pests and diseases such as malaria and locusts, which impact both human health and agricultural output. In sum, climate change has an immediate impact on incomes, household food security and health.

The challenges posed by climate change on rural populations are compounded by high levels of poverty, and lack of access to or high cost of financial services, education, and healthcare. These long-run changes in weather, along with extreme weather events such as intense rainfall and flooding or severe droughts, are motivating increased rural-urban migration in many regions – shrinking an economy’s agricultural capacity and possibly worsening food security.

We interviewed farmers in both Nigeria and Mexico to understand their experiences of climate change.

In Mexico, climate change is projected to impact agriculture primarily through warmer and drier weather.

This is expected to decrease yields of staple crops such as maize and between 40 and 70% of agricultural land could become unsuitable for farming by 2030.In addition, complex water management policies implemented in response to water stress limit the ability of farmers to use irrigation, leaving them dependent on precipitation. The region also expects an increase in the severity of hurricanes, which will damage homes, assets, and crops, particularly in Eastern Mexico.

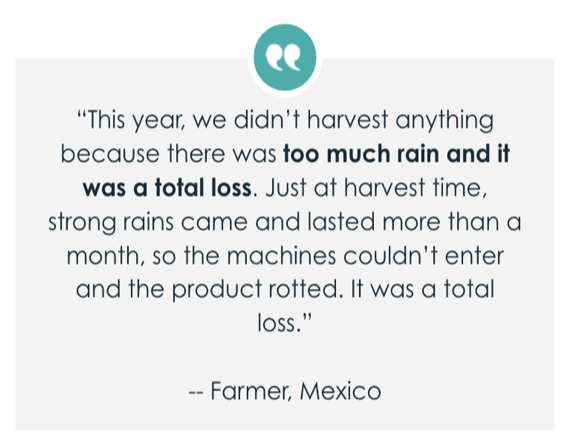

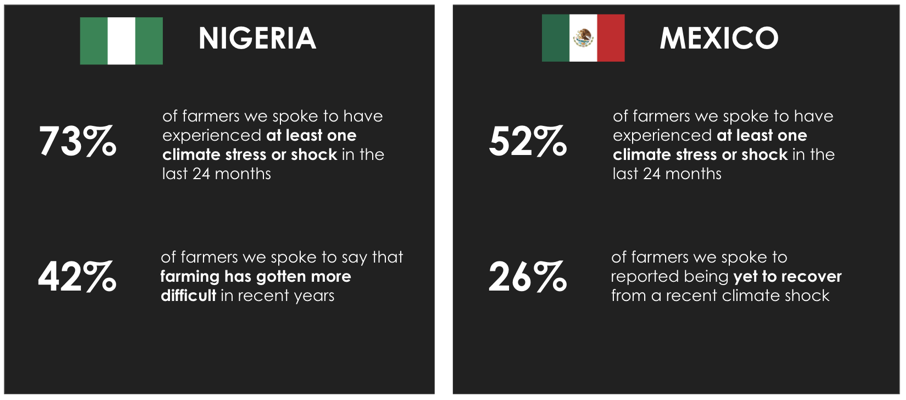

Over half of farmers in Mexico we spoke to have experienced at least one climate shock in the last 24 months.In line with climate change models, drought and severe lack of rain were the most commonly reported shocks among farmers.Among the groups we surveyed, 26% of farmers reported they had yet to recover from climate shocks they had recently experienced.

In Nigeria, climate changes are projected to increase total rainfall and temperatures across the country. The impact on yields of these changes varies significantly by geography within the country and by crop type. For example, in Northern Nigeria, farmers of millet, onion, and tomatoes are projected to have increased yields due to climate change, while farmers in Southern Nigeria of staples such as maize and yams will see a decrease in yields. Not only is total rainfall expected to increase, but the frequency of extreme rainfall events that lead to large runoffs and flooding is also expected to increase.

42% of the farmers we interviewed in Nigeria reported that farming has gotten more difficult in recent years. Farmers who reported that farming is getting more difficult cited increased input prices and climate change impacts. Flooding (58%) and drought (31%) were both reported as common shocks, depending on the region. Concerns about rising input prices are likely the result of supply chain disruptions due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and recent policies enacted by the Nigerian government limiting the import of inputs in an attempt to produce more inputs locally.

We asked farmers in Nigeria about their experience with 11 different risks, ranging from natural disasters to medical emergencies to death of livestock. The risks most commonly experienced were:

- Large increases in the price of inputs – almost 90% believe that it is very or moderately likely that they will be faced with a large increase in price of seed and other inputs

- Income earners losing their ability to work – 0% reported they were moderately or very prepared for their income earner stopping work

- Eviction from their land – 94% had experienced eviction from home or land

- Drought – every farmer we spoke to had experienced damage from drought

Whereas nearly 75% of farmers report that they are moderately or very prepared for medical costs or drought, fewer than 40% say they are similarly prepared for a natural disaster (e.g., flood) or for lack of liquidity to buy inputs.

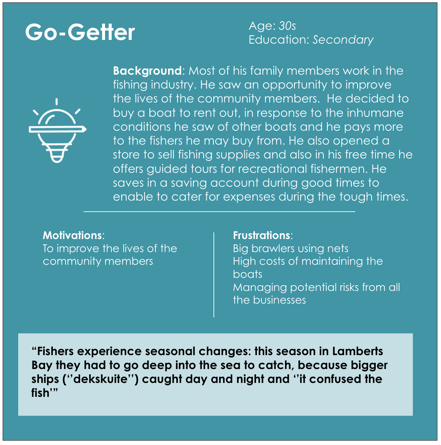

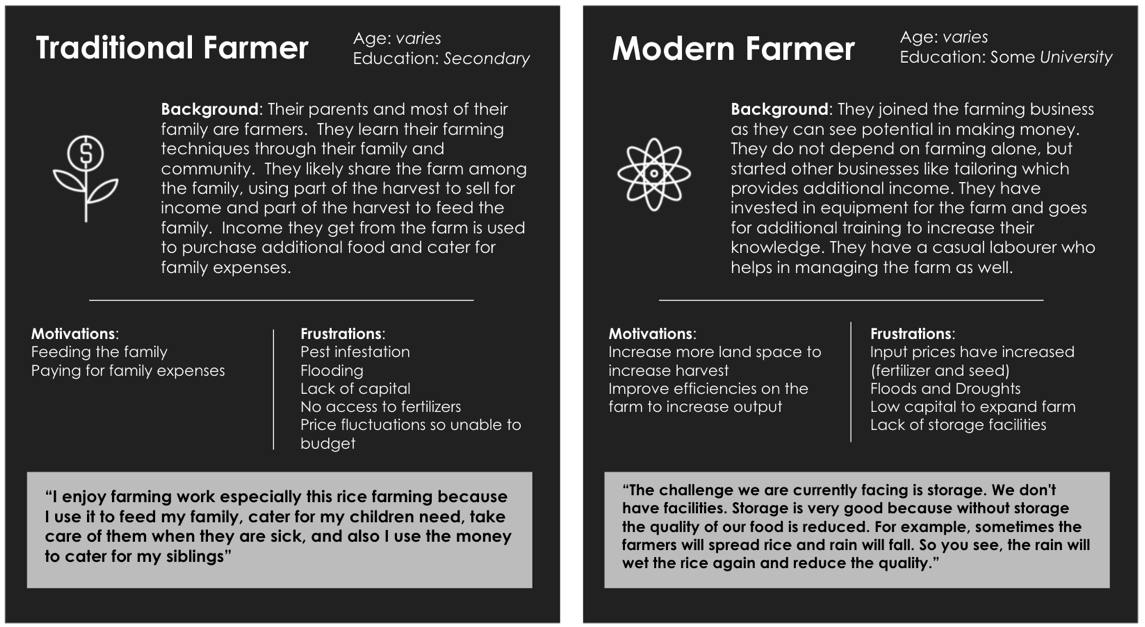

From our research across both markets, we categorized two personas of farmers:

COASTAL EXPERIENCES

600 million people globally live in coastal areas below 10 meters of elevation.

These populations are some of the most vulnerable to extreme weather events, such as cyclones, storm surges, and heavy rainfall. Furthermore, lower-income households in coastal cities are more likely to be in highly-exposed areas, in households constructed from poor building materials unable to withstand strong winds and rain. Rising sea levels also increase the risk of storm surges and flooding and may cause over 265 million people to be displaced.

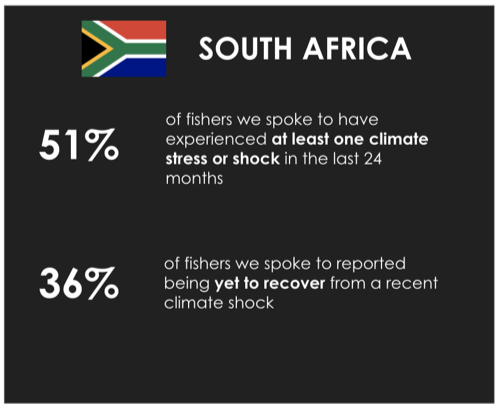

Among the most vulnerable in coastal areas are fishers, who are dependent on natural disasters like farmers. 97% of the world’s fishers live in developing countries, where fish constitute over 50% of locally consumed protein. Changing ocean temperatures and salinity, compounded by unsustainable fishing practices, overfishing, and local environmental degradation, are reducing catch volumes and variety for many small-scale fishers. Further, large regions of the tropics could see a reduction in fish catch of up to 40% by 2050. The increasing severity and frequency of extreme weather events is also reducing the number of days fishers can safely work at sea. We spoke to coastal small-scale fishers in South Africa about their experience of climate change.

97% of the world’s fishers live in developing countries, where fish constitute over 50% of locally consumed protein. Changing ocean temperatures and salinity, compounded by unsustainable fishing practices, overfishing, and local environmental degradation, are reducing catch volumes and variety for many small-scale fishers. Further, large regions of the tropics could see a reduction in fish catch of up to 40% by 2050. The increasing severity and frequency of extreme weather events is also reducing the number of days fishers can safely work at sea. We spoke to coastal small-scale fishers in South Africa about their experience of climate change.

South Africa has two distinctive coastlines for fisheries and marine life. The West Coast has water that is cold, flowing up from Antarctica, while the Indian Ocean on the East Coast is warm and home to a large variety of tropical fish. Climate change is projected to increase the temperature of the ocean globally.

Fish are highly sensitive to changes in temperature, so will move to cooler waters along with the changing ocean temperatures. The impact of these changes on fish catch is hard to predict, because local fish volume and availability is compounded by overfishing, pollution, and ecosystem degradation – all three of these factors are also of concern in the South African context.

In the case of fishers we spoke to, climate change has been widely observed but its impact on fish catch has been mixed. Almost 30% of fishers we spoke to reported they had observed loss or destruction of fishing habitat. But, changes in sea temperature have had mixed results; some report that fish is more scarce but others note that some fish varieties are more available.

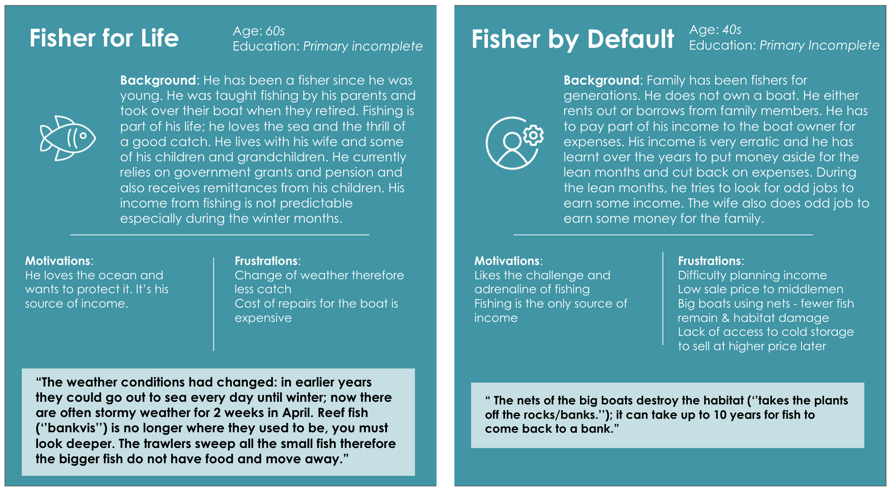

The negative impact that most fishers cited was not from climate change, but from overfishing and poor fishing practices by larger boats and trawlers. As such, the biggest problem that fishers cite is not lack of fish, but rather high costs of inputs and low predictability of earnings. Over 80% of fishers we spoke to reported that their income is unstable, even as over half reported that the vast majority of their incomes come from fishing (80%). Even with this instability, few are able to manage their income across these ups and downs. Some rely on odd jobs and others rely on other income earners, while a few are able to save.

The negative impact that most fishers cited was not from climate change, but from overfishing and poor fishing practices by larger boats and trawlers. As such, the biggest problem that fishers cite is not lack of fish, but rather high costs of inputs and low predictability of earnings. Over 80% of fishers we spoke to reported that their income is unstable, even as over half reported that the vast majority of their incomes come from fishing (80%). Even with this instability, few are able to manage their income across these ups and downs. Some rely on odd jobs and others rely on other income earners, while a few are able to save.

Even with these challenges, most fishers we spoke to are not thinking about how to plan for the future. Only 10% of fishers we spoke to had plans to expand or adapt their fishing practice; the rest planned to continue as they have been. This may reflect the fact that more than 60% indicated that their parents and earlier generations were also fishers.

From our research in South Africa, we categorized three personas of fishers:

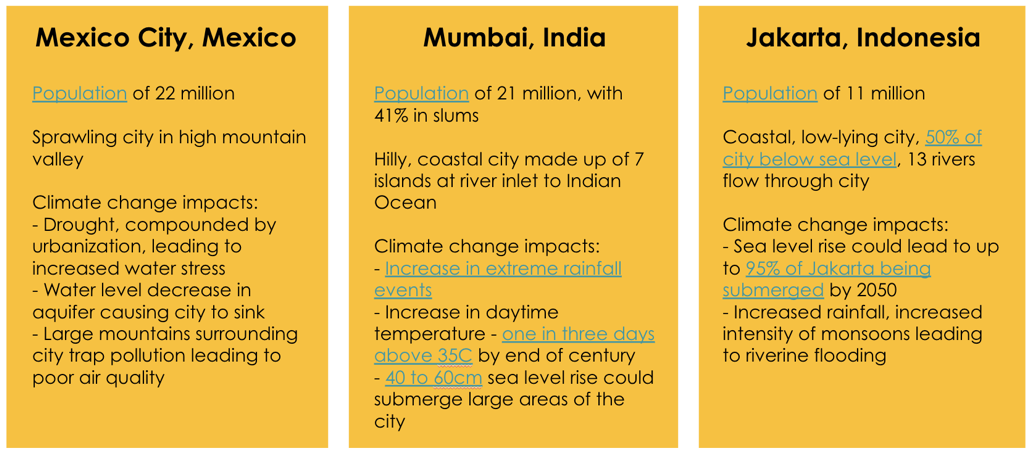

URBAN EXPERIENCES

An estimated 1.28 billion people globally live in urban slums.

As the climate changes, urban dwellers will be increasingly exposed to extreme heat and urban heat islands. The masses of concrete and asphalt that are the foundation of most cities can make daytime temperatures up to 7 degrees fahrenheit hotter than surrounding areas. Many lower-income urban dwellers work outdoors, which means they are exposed to extreme heat and unable to work during certain seasons and times of day. By 2030, inability to work due to extreme heat could result in 80 million jobs lost.

Many city dwellers will also be exposed to extreme weather events such as cyclones and flooding. Low-income communities are more likely to live in disaster-prone areas of cities, such as on hillsides or near bodies of water, in homes made from low-quality building materials. The same concrete and asphalt foundation of cities also reduces the ability of water to be absorbed into the ground, dramatically increasing the potential for flooding after heavy rainfall. Households in these communities are also likely to hold their assets in physical goods and cash, and will lose proportionally more wealth during climate disasters compared to wealthier households.

Climate change impacts in the urban context are unique based on the particular local climate exposure of each geographical location.

The challenges posed by climate change on low-income urban dwellers is compounded by lack of access to basic services such as clean water and sanitation, limited access to healthcare, high population density, and increasing urbanization and migration.

Cities are critical players in the fight against climate change. Cities currently are home to about half the world’s population, yet consume an estimated 80% of the world’s energy. To limit further climate changes impacting cities themselves as well as rural and coastal communities, cities must be on the forefront of reducing their emissions and build low-carbon growth pathways, settlements, and economies.

Research was not completed with urban climate vulnerable communities and is an important next step furthering our understanding of climate impacts.

NEXT STEPS

The research completed here paints a picture of the experience of climate change of select climate vulnerable populations in a few particular regions.

From our research with farmers, we see that they are very aware of climate change impacts especially where there are direct impacts on their harvests. The impacts of climate change are compounded by other risks and challenges that farmers face such as eviction from their land and increases in prices of inputs.

For fisher communities, we see that despite 51% saying that they have experienced a climate shock in the last 2 years, the longer-run impacts of climate change are less clear – as in some places local conditions for fishing are actually improving – and are hard to distinguish from the impact of overfishing and local environmental degradation.

Climate changes and vulnerability are inherently local and personal, and more research should be completed to continue to understand the impacts and potential strategies to build resilience for low income populations globally.