A Day in the Life of a Shopkeeper

Running a Small Shop is a Tough Job

When I was growing up, the corner store was a convenient place to pick up a half-gallon of milk, a loaf of bread or any other household staple that had run out. You could also go to the corner store to pick up stamps, some ibuprofen or a bag of chips. Depending on where you’re from in the US, you might call this place a deli, a convenience store or a bodega. These stores are a kind of neighborhood pantry and seemingly exist in their own versions in different countries. Whether you’re in India, Mexico or Kenya, you’ll see this local retail shop phenomenon repeat itself under a different name.

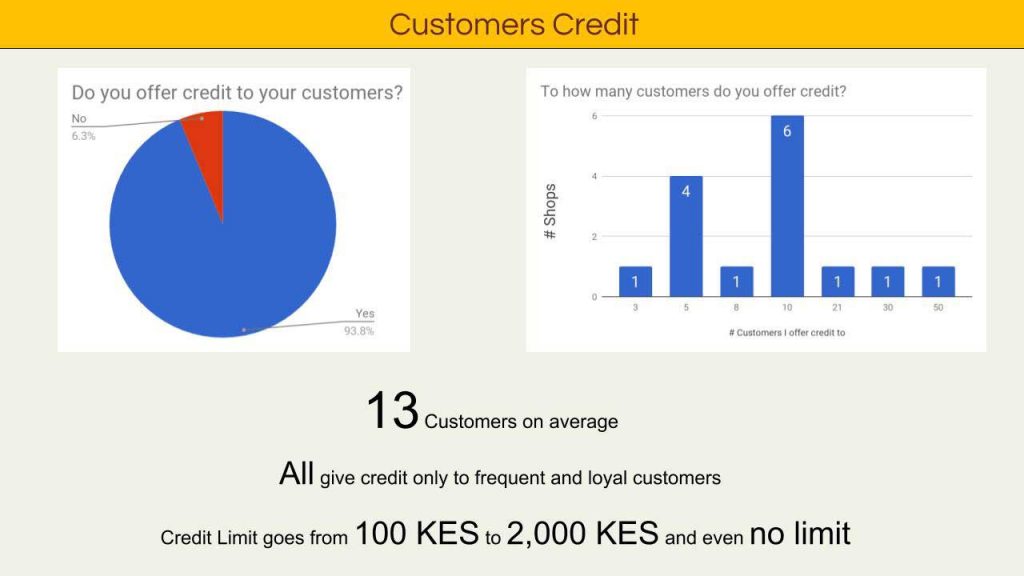

The small shop is a vital lifeline of communities and is also at the center of a complex ecosystem. First, these shops sell to millions of low-income consumers, to whom they sometimes extend credit. Shops also buy from a range of suppliers including manufacturers, wholesalers and distributors, such as the Coca-Cola tuk tuk drivers or random hawkers that pass by the shop. Often a solution to last-mile distribution challenges, shops act as points of sale for airtime or as cash in cash out (CICO) agents, usually for multiple operators and for financial institutions such as banks. Unlike supermarkets, shopkeepers establish personal relationships with their customers. Going to the corner shop is more than a mere transaction, it’s a moment to socialize by chatting about life matters, family and the weather.

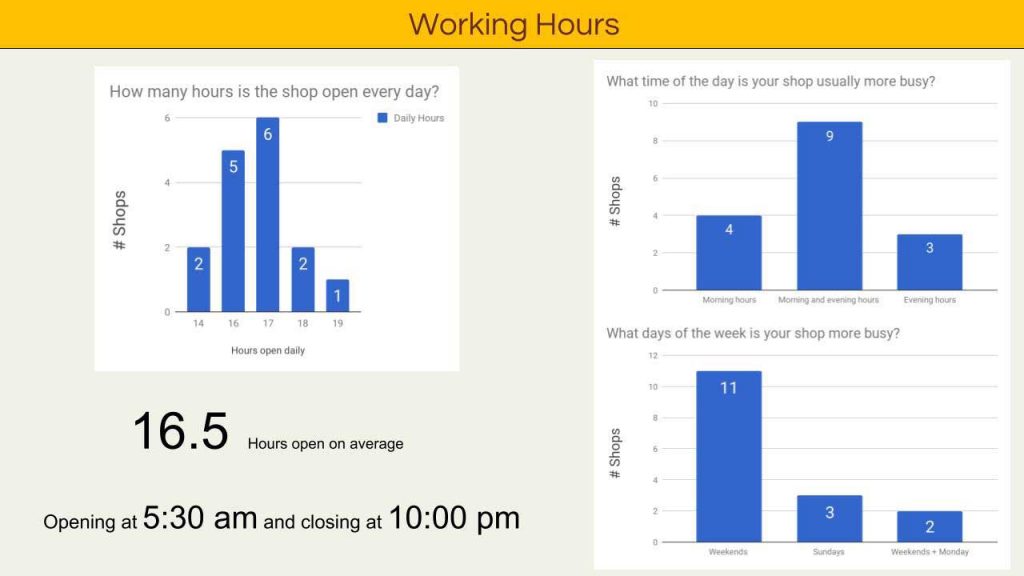

1. True or false? On average, a duka (a small shop) is open more than 15 hours a day (answer below).

In Nairobi, we’ve been looking closely at dukas, Swahili for the the proverbial informal retail store, to learn about shopkeepers, their needs and how to better serve them with digital solutions through our program, FIBR. To better understand how these shopkeepers run their businesses, we recorded their daily interactions from 7am to 5pm with customers and suppliers. Every time a customer visited the shop, we captured the time of day, products sold, quantities, prices, and mode of payment. Spread across different locations — dukas are often located in risky and vulnerable areas — we observed and recorded data in 18 shops.

From Dawn till Dusk

As a shopkeeper, you wake up between 5am to 6am to sell milk, bread and mandazis (African doughnuts) to your customers on their way to work. You sell at low margins and volumes (sometimes even at a loss), with stiff competition since similar shops with the same products and prices are located every 10 meters. To keep customers loyal, you extend credit without any type of formal accounting and verifiable records. The day hours are normally less busy, unless you are located near a station, a main street or a business district. During the slow hours you re-stock and organize the shop until your customers return home in the evening, when the shop gets crowded again. This is the drill day after day.

2. True or false? Fifty percent of the dukas in Nairobi extend credit to customers (answer below).

Many Decisions to Make

Miriam is really struggling with her business as a shopkeeper. In her early forties, she has three kids in school who are 21, 17 and 8 years old. She started the business a year ago, after she got divorced and left her rural surroundings to come to Nairobi. Now she is desperately looking for working capital to stock her empty shelves. Initially, her brother supported her with starter funds to launch the store and also paid for the rent. She would generate enough revenue per day when she could keep shelves stocked to satisfy demand. However, she doesn’t have enough funds to purchase stock because of the school fees she has to pay foremost for her children. Maybe Miriam just underestimated what it takes to run a shop and make ends meet for her and her family. As a shopkeeper, she needs to make key decisions for her business to succeed.

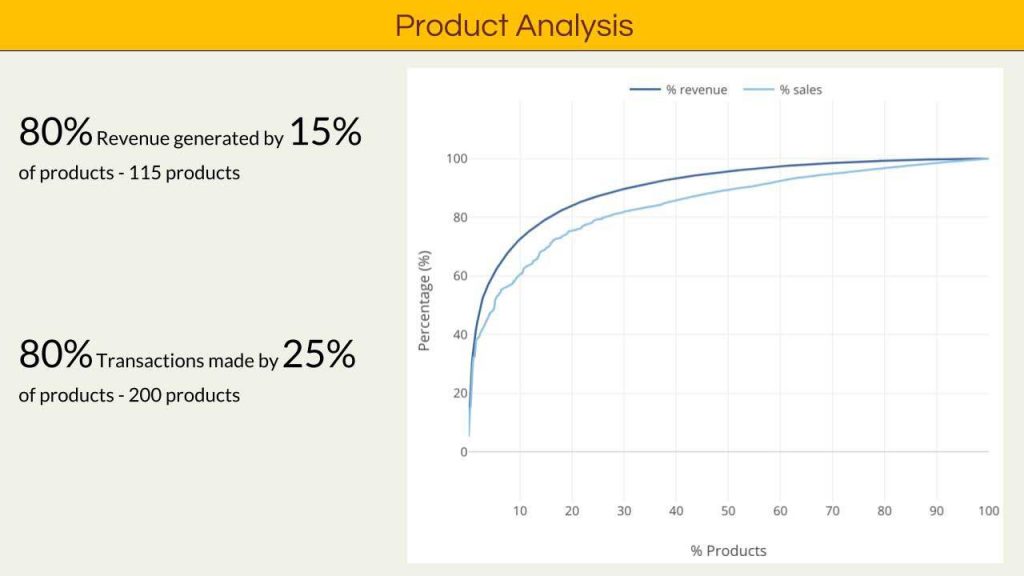

3. True or false? Eighty percent of the revenue of a shop is generated by 50 percent of the product (answer below).

For example, she needs to be able to understand her numbers, which are largely based on pen and paper. Some shopkeepers try to keep records, at least of supplier transactions and basic figures about the business. But it’s hard for shopkeepers to adhere to the practice since they don’t really derive any value from the record keeping. And while more than half of the shopkeepers in urban Nairobi already have a smartphone, it doesn’t mean they are prepared or able to use the smartphone as a business instrument. So imagine trying to adopt digital accounting tools that require you to change how you do things while adding an extra layer of complexity. It’s not a surprise that a majority of the shopkeepers we speak to perceive digital tools as a waste of time.

Second, Miriam has to figure out the right product mix to run her business well. We saw that 80 percent of the revenue is generated by 15 percent of the products, which are the low-margin staples: dairy products, airtime, oil, bread, rice, sugar, flour, detergents and sodas. These products move off the shelf quickly and shopkeepers must keep them stocked or they run the risk of losing customers to other shops nearby. A well-stocked shop means having a variety of goods that includes beverages, food, cleaning products and candy. It also means carrying items that turn over less frequently, such as toothpaste, shampoo, painkillers and school supplies such as pencils, notebooks and math exercises.

Instead of stocking up goods at home, customers take advantage of the shop’s proximity to buy what they need on demand or in sachet quantities, such as 50 grams of detergent to do one load of washing or a portion of maize flour to make the day’s ugali (cornmeal porridge). As a shopkeeper, Miriam needs to sell items by “breaking bulk,” that is, single units of prepackaged items, such as loose cigarettes, individual diapers or pouring out a portion of cooking oil from a larger bottle.

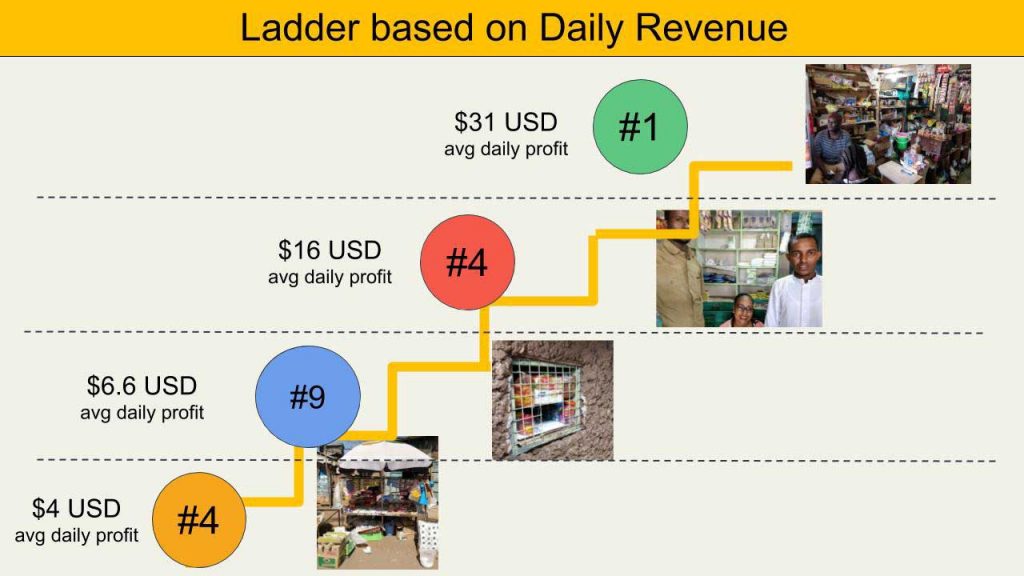

4. True or False? Most small shopkeepers earn LESS than $6 a day (answer below).

Cash Flows Matter

Or maybe, Miriam really needs a good solution for smoothing out the ups and downs of her cash flows. Credit could help her finance working capital to keep enough inventory to meet demand and keep her shop going. If her business were better off, it could also be a mechanism for her to expand through adjacent lines of business, such as selling liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), or increase storage capacity.

Recently, Miriam joined an ASCA (an Accumulated Savings and Credit Association — an informal savings group in which members make a monthly deposit to a group fund which is lent out to a third party with interest) where she is hopeful she will be able to borrow after participating for a few months. She has a smartphone so we asked about digital loans. Once she borrowed from M-Shwari to pay her ROSCA (a Rotating Savings and Credit Association) but her credit limit was only KES 240 ($2.34), which she defaulted on and resulted in her losing the service. She still has been trying to access a digital loan from KCB M-Pesa but with little success.

In a market like Kenya, the lending space is overcrowded. About 400,000 Kenyans were blacklisted for amounts less than 2 USD. And not all merchants want credit. “Tell me why if I have cash, I should pay on credit?” they say. They are right. Credit has to be offered responsibly and appropriately for the need, such as after a financial crisis, paying for school fees or an advance to purchase stock. For example, our partner Sokowatch, an e-commerce platform for informal retailers in urban Africa, offers shopkeepers the ability to order products and pay for the items later in the week with cash on hand from sales, easing their cash flow constraints. As part of our engagement with Sokowatch, we are testing a smartphone-based in-kind lending solution as a value-added service for merchants.

Watch the video to learn about how we worked with our partner, Sokowatch

What do Shopkeepers Aspire For?

Shopkeepers love being their own boss and having the freedom to run their businesses their way. These shops are normally family-owned businesses, and very often the shop is an extension of the shopkeeper’s home. When we ask shopkeepers what they dream of, they have aspirations to move up. It might mean becoming a wholesaler, a “super” shop similar to a mini-mart, or opening another shop with employees to operate it. Some shopkeepers will earn enough for their daily expenses while managing enough cash flow to maintain stock and meet demand. A few others will have quite a knack for running a shop and succeed in earning above average to expand their business. Sadly, the reality is that a lot of shops end up shutting down, sometimes because of a lack of management skills, or because surviving in such a competitive landscape is extremely tough. With these challenges in mind, we are piloting a WhatsApp group with about 15 merchants to test a micro-consulting approach that guides merchants with tips, tricks and insights to help them run better businesses.

Answers to Questions:

About Javier Linares

For over eight years prior joining to BFA, Javi was Frogtek’s Product Manager of innovative technology solutions for mom-and-pop micro retailers in emerging markets such as Mexico and Colombia. At BFA, Javi participates in end-to-end projects that focus on supporting tech-enablement in the financial sector and brings skills such as software development, product design and management, customer experience and data analytics.