Learning From Our Past: Successful Ecosystem Evolutions Follow a Common Path

In early 2021, BFA Global, CGAP, UNCDF’s Better than Cash Alliance, PayPal, the UN’s Race to Resilience, and the World Resources Institute established the Digital Finance for Climate Resilience (DF4CR) Task Force to understand the opportunity for digital finance to enable access to climate resilience solutions, and how we can accelerate the emergence of an innovation ecosystem for this emerging sector. This work culminated in the development of the Framework for Action, which maps the essential next steps to seed and grow the DF4CR ecosystem.

To develop the Framework for Action, the DF4CR task force reflected on past experience in three adjacent ecosystems that serve vulnerable, low-income populations: microfinance, PAYGo solar, and inclusive fintech. Like DF4CR, these three ecosystems harness finance and technology to serve low-income people, who are also vulnerable to climate change. These communities typically lack access to formal financial services and safety nets, can have nature-based livelihoods, and either live in low-income urban settings or reside in rural areas.

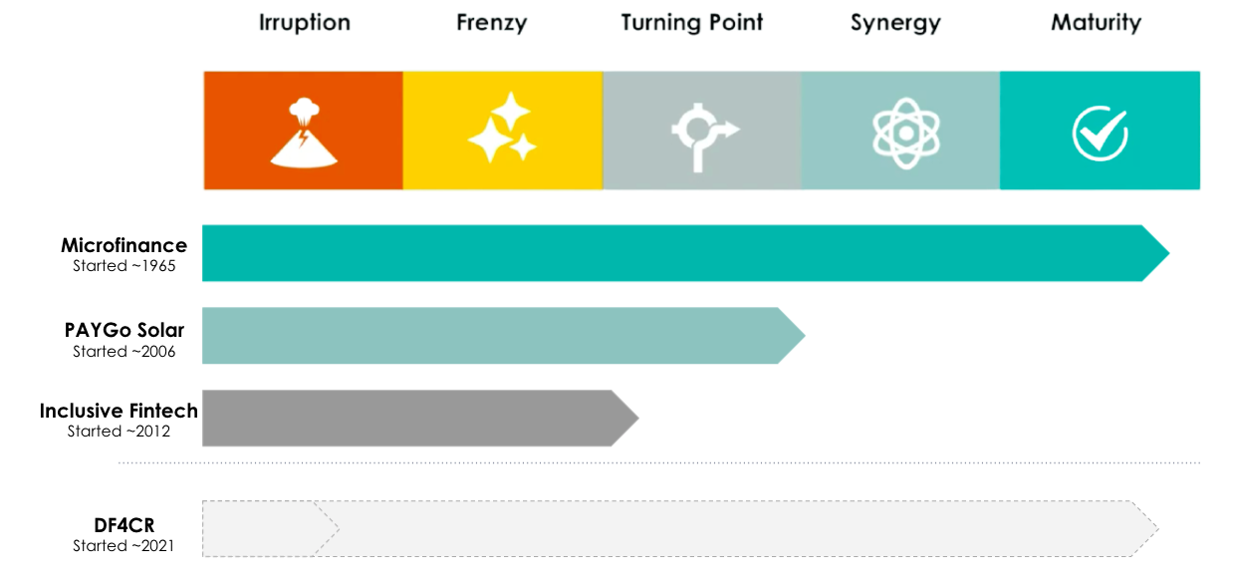

Three ecosystems studied to develop the DF4CR framework

In each of these three ecosystems, innovators created novel solutions to deliver value to underserved people. These solutions succeeded in reaching scale by motivating and consolidating a supportive ecosystem of actors and stakeholders. The task force therefore studied the evolution of each ecosystem to capture relevant lessons that can foster growth in DF4CR.

The Evolution of an Innovation Ecosystem

The task force adapted the technology evolution framework developed by Carlota Perez, to characterize the evolution of the microfinance, PAYGo solar, and inclusive fintech ecosystems. According to Perez, a technology ecosystem typically has five distinct phases of evolution:

- Irruption [1] is where a new set of solutions are invented and initial diffusion happens. It is a generally slow stage and is contained to a tight group of people and organizations.

- Then a Frenzy period of massive growth begins, with new solutions, providers, and individuals flooding the market.

- Eventually, there is a Turning Point, which could be an event or a phase that defines the future mode of growth. This could be from regulatory intervention, or a bubble burst that refocuses attention on sustainable growth.

- During the Synergy phase, the foundations and infrastructure are set and conditions allow for expansion and economies of scale.

- Finally, Maturity is reached, where markets are getting saturated, and new ideas and businesses are being spun off into the Irruption of other adjacent sectors.

The five phases of an ecosystem’s evolution

Through desk research and consultations with experts and observers to these adjacent ecosystems’ emergence and development, the development of each ecosystem was mapped against Perez’s framework to look for common themes, critical moments, and seminal interventions that could be applied to DF4CR. The goal was to identify and better understand the conditions and critical enablers that allowed for a step-change in each of these adjacent ecosystems, with a particular focus on how each was able to transition from Irruption to Frenzy, given that DF4CR is only now emerging and entering the Irruption phase. For each adjacent ecosystem, the critical enablers of change were identified for each ecosystem phase along with the role played by key actors in five groups:

- Innovators, developing and bringing to market DF4CR solutions

- Catalytic Funders, sparking and de-risking those innovations

- Investors, funding the growth and long-term impact of the solutions

- Enabler Organizations, addressing knowledge gaps, building partnerships, and building communities of practice

- Governments and Policymakers, public sector bodies acting as regulators, financiers, and customers for innovators

The five groups with critical roles in an ecosystem’s evolution

Insights from Adjacent Ecosystems

The sections below present insights derived from research into the three adjacent sectors. They focus on the critical interventions in each phase, mapped against the actor group that was most responsible, along with summarized lessons from each that can be applied to DF4CR.

Map of how the three adjacent ecosystems evolved

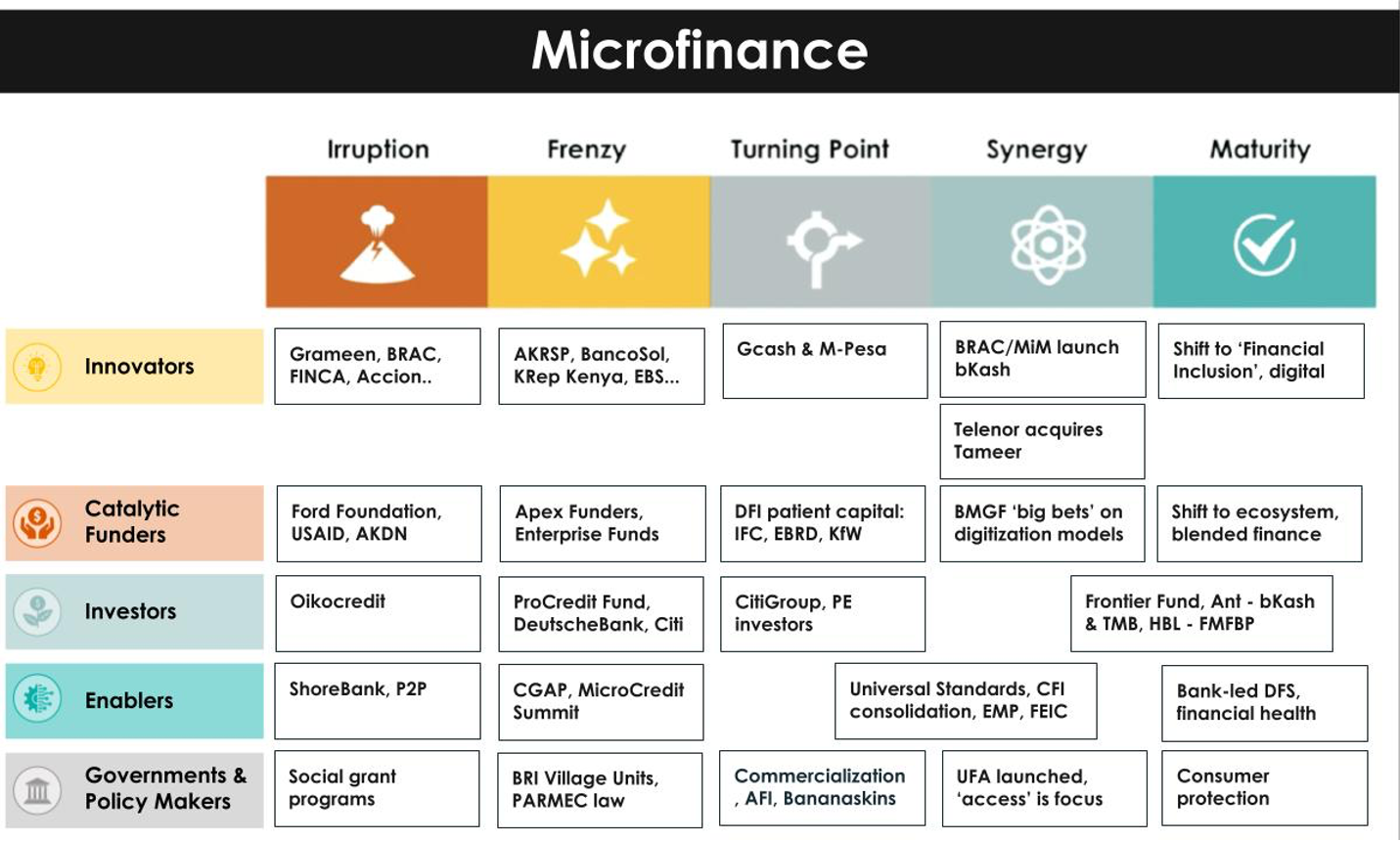

Microfinance

Microfinance, now more commonly included in the broader envelope of ‘inclusive finance’, emerged in the 1960s and 70s with pioneers such as Mohammad Yunus working to understand how to provide credit to extremely low-income, excluded populations, effectively and safely. Many of the early innovators were non-profit organizations focused on poverty alleviation such as PRODEM (later BancoSol), Accion, Grameen, and BRAC. Catalytic funders like the Ford Foundation played a critical role through champion “intrapreneurs” that supported the innovators with their first grants and facilitated knowledge exchange between existing and emerging innovators. As those proof of concepts emerged, more funders like USAID and DFID provided the next round of funding that created some models that were replicable. Early innovators’ success created a ripple effect of emerging entrepreneurs getting training from the first generation and replicating these models in other markets.

Early investors included mission-focused debt providers, particularly Oikocredit as early as the late 1970’s. As loan portfolios grew and cash flow viability was proven, commercial banks began to develop wholesale lending partnerships with maturing microfinance institutions in local markets. Banking multinationals, led by Deutschebank and Citi, launched specialized microfinance lending and structured debt finance units. Growth also led to an emerging cadre of technical expertise providers developed by early funders like Ford Foundation and USAID, and/or through those interning or volunteering with early microfinance initiatives that accelerated innovators’ businesses. Enablers grew to include knowledge centers like CGAP, focused on learning about the sector, the various innovations powering it, and how to scale them.

Microfinance is now estimated to reach 140 million people globally, over 80% of whom are women. Microfinance is now thought to be at the maturity stage of ecosystem development, and has been critical in seeding other adjacent ecosystems such as inclusive fintech and digital financial services.

Map of key players, important moments, critical knowledge products and paradigm shifts for microfinance

Focusing only on the transition of microfinance from Irruption to Frenzy, so we can distill insights that can be applied to DF4CR, there are several key strategies and learnings:

- The identification and cultivation of visionary, early risk-taking disruptors with the individual commitment, networks, and personal resources is critical to test new business models and technology.

- Intrapreneurs within funding organizations that bet on innovations truly can be “catalytic.” These champions, public and/or private, are important in order to take ownership of early risk-taking ‘bets’ on emerging disruptors and innovators, enabling some innovators to “fail fast forward” and shortening timelines to take-off, scale, and replication.

- Growth of country and regional-level industry organizations, apex funding institutions, and research / policy groups will play a key role in identifying, describing, and parameterizing emerging ‘best practice’ business models to make replication, investment and scale feasible.

- Facilitation of global and regional forums is needed for policy and funding coordination, research, and standard outcome metrics for donors and investors in emerging sectors.

- Alignment of early commercial risk-capital to drive and grow business models with clearly defined financial and non-financial parameters for success is important to ensure that there is a clear focus on impact and productive growth.

- Regulators need to leave space for innovation to mature before implementing oversight and constraints can support further growth of innovators.

- Regulatory collaborations and professional networks should be cultivated to identify emerging good practices without stifling innovators’ growth and scale.

- Cautionary lesson: Customer protection and information sharing practices must be defined, implemented, and enforced early in the emergence of an ecosystem to protect consumers. Microfinance faced a wave of concerns in the early 2000’s related to transparency and consumer protection. Regulators, catalytic funders and enablers can play an important role in ensuring that data and consumer protection are defined across the entire ecosystem from an early stage, and also that they are enforced across geographies and organizations. In today’s world with dramatically more data compared to the early 2000’s, this lesson is especially critical for the emergence of DF4CR.

PAYGo Solar

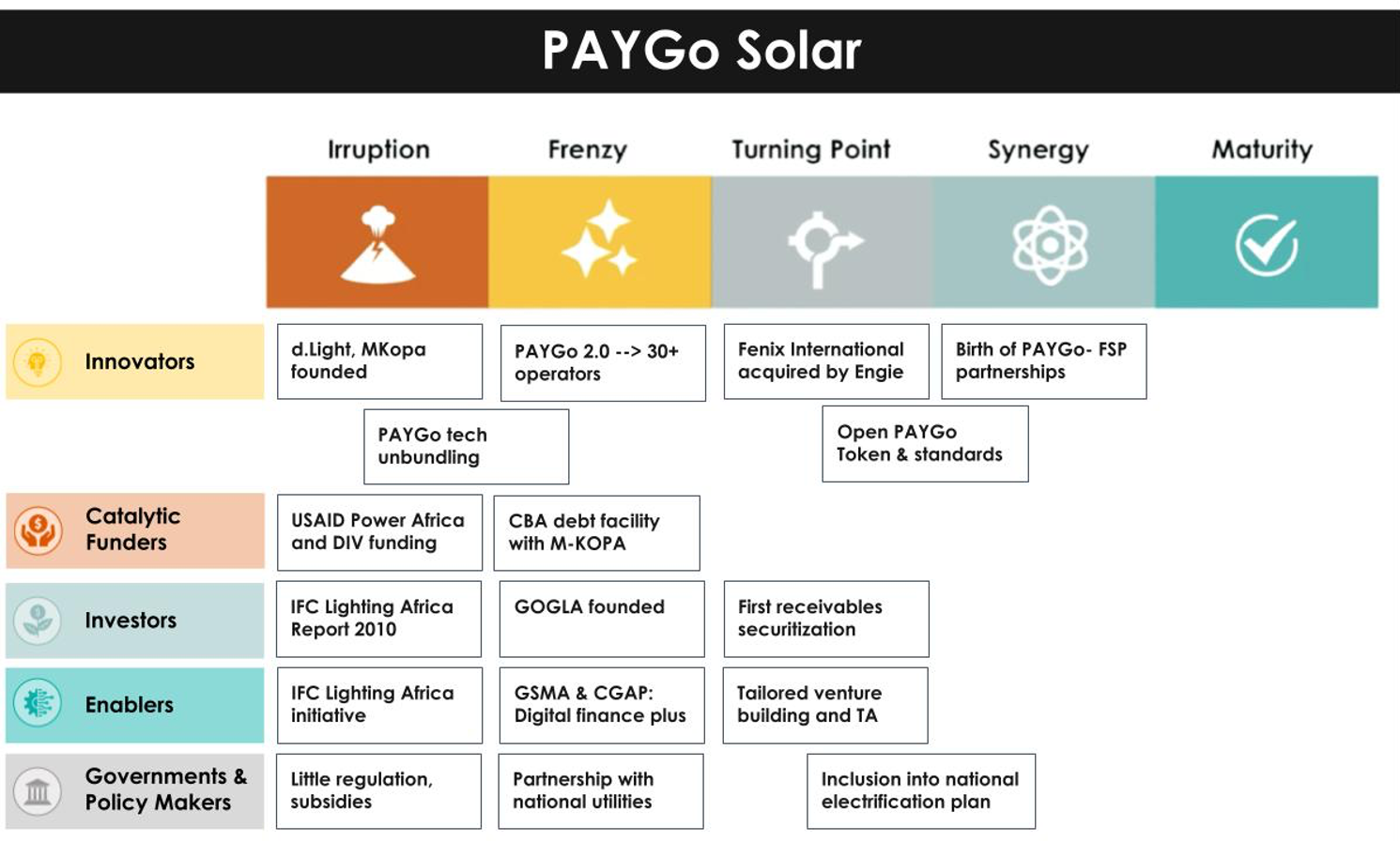

PAYGo Solar emerged in East Africa circa 2006 as an experiment to address rural electrification challenges with a combination of solar energy, which was going through a dramatic reduction in cost, and digital finance, since mobile money was scaling rapidly among rural and low-income populations in the region at the time.

The first innovators, such as d.Light and M-KOPA, were supported early on by catalytic funders like USAID and the Gates Foundation, which recognized the social and economic development potential of off-grid, affordable solar energy systems. The first successful proof of concepts attracted investor interest, and innovators rushed to grow their customer base, regardless of cost, to demonstrate traction for investors. A critical moment early in the emergence of PAYGo was the launch of IFC’s Lighting Africa initiative that identified and influenced policy enablers, conducted rigorous market sizing, and drove industry and market creation. It was followed by knowledge contributions from additional enabler organizations such as GSMA, CGAP and GOGLA.

PAYGo solar today is believed to be in the turning point phase of ecosystem evolution. The sector is characterized by tremendous capital flows and valuations, and a proliferation of innovators that are disaggregating the value chain. There have been a few high-profile acquisitions, like Fenix international and Simpa being acquired by Engie, and some poor portfolio performance leading to bankruptcies (e.g. Mobisol) and large players pulling out of high-potential markets (e.g. M-KOPA from Tanzania). There is an emerging focus on sustainable growth from industry bodies such as GOGLA, a move away from the growth-at-all-cost ethos that drove many of the failures and recent consolidations.

Map of key players, important moments, critical knowledge products and paradigm shifts for PAYGo Solar

Key lessons from the PAYGo solar sector’s transition from Irruption to Frenzy that are relevant for DF4CR:

- Early identification of pathways for rapid growth including debundling hardware and software are necessary to unlock more rapid and scalable innovation (e.g., Angaza as a digital payments platform for PAYGo solar companies).

- Partnerships with large incumbent organizations or governments can dramatically reduce the cost of accessing and serving customers, can rapidly scale the customer base, and can provide access to synergistic data and infrastructure (e.g., M-KOPA’s partnership with Safaricom).

- Catalytic funders’ support of early market intelligence like market sizing, and technology and business model landscaping was critical for early innovators to “point to” when raising money from investors in the early days of PAYGo solar.

- Catalytic funders deliberately established market-creating and orchestrating programs (e.g. IFC Lighting Africa, GSMA Mobile for Development Utilities), and industry gatherings (Lighting Africa symposiums), which was important in further seeding the “paradigm” of PAYGo solar.

- Accelerated tech development and derisked operational rollouts via grant funding and debt financing from DFIs and commercial banks can be important to generate higher confidence for commercial equity investors to enter the market.

- Enabler-bodies establishing product quality standards, organizing industry events, writing case studies, performing market sizing, and conducting public good research that documents the social, economic, and environmental impacts is key to ensuring that the industry learns and grows together, and protects consumers.

- Regulation can enable rapid innovation and even the playing field (e.g. VAT exemption of PAYGo products, introducing smart subsidy models like results based financing for hard to reach locations can boost growth in remote areas).

- Cautionary lesson: Innovators and investors need to ensure they are driving towards “sustainable growth”. Investors became excited about the potential scalability of PAYGo solar, so many traditional equity and venture capital vehicles began investing but with the need for extremely high growth and short return timelines. There was a heavy focus on “growth of customer base” metrics, leading to a growth-at-all-costs mentality for PAYGo providers, and eventually to portfolio quality issues, a few bankruptcies, loss of investor confidence, and negative consequences for consumers. For lending-based DF4CR models (PAYGo irrigation or farming equipment, loans for disaster rebuilding or adaptation), more patient capital and facilities need to be developed that incentivize and are aligned with sustainable growth return profiles – PAYGo solar would have greatly benefited from more patient capital in the early stages of ecosystem development.

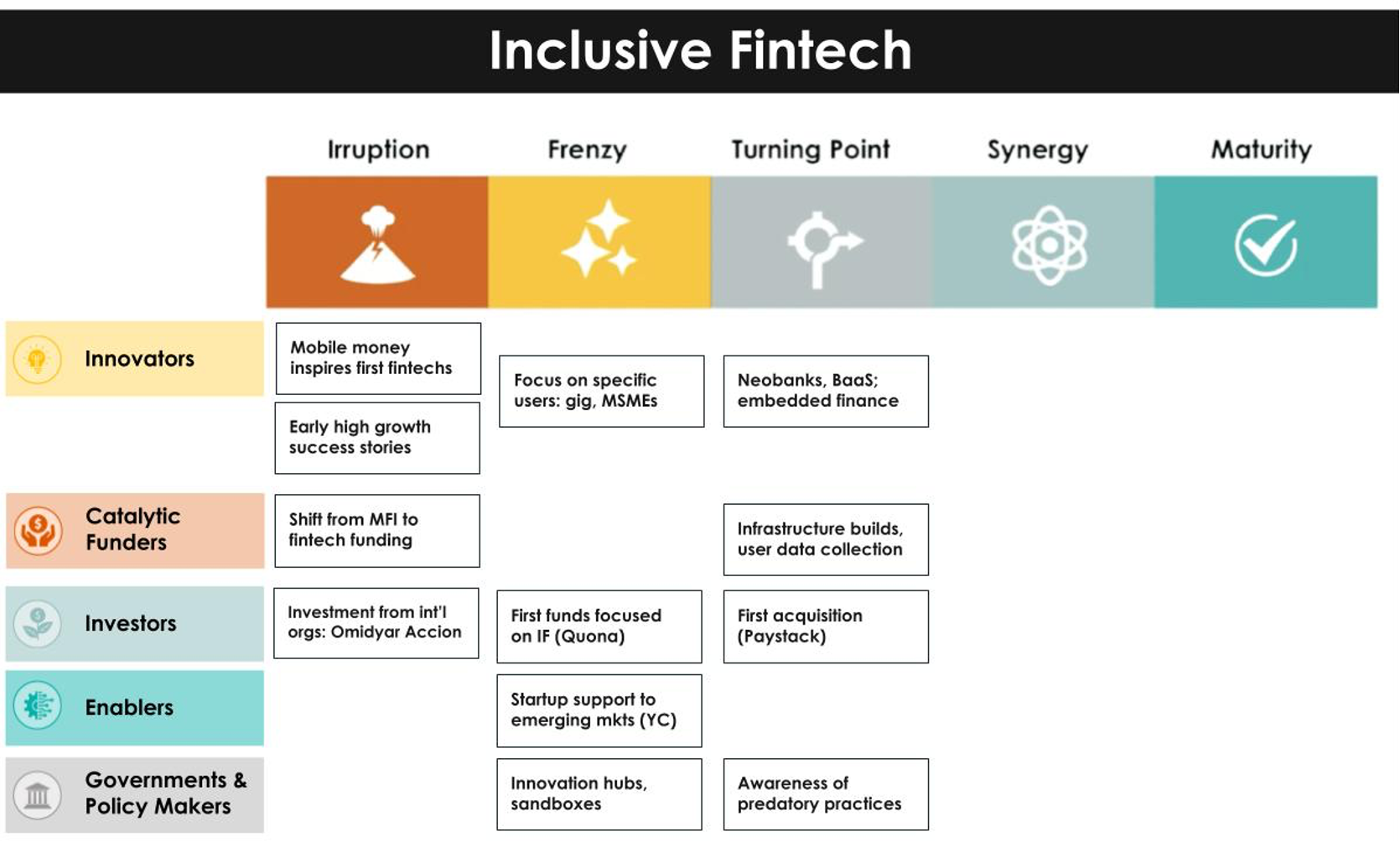

Inclusive Fintech

Inclusive fintech is the most recent of the three ecosystems to emerge, and it did so off the back of microfinance and mobile money innovations in emerging markets. Early innovators like Tala and Branch scaled rapidly, generating excitement and interest in the potential of fintech for low-income populations. Catalytic funders such as Omidyar Network and Accion were the first to identify and invest in the emerging ecosystem. Over time investors and funds like Quona Capital, and Flourish Ventures emerged specifically for this sector. Enablers have started to manage industry events, awards, and startup support programs specifically focused on inclusive fintech such as Catalyst Fund.

More recently, impact and growth stories from Tala, Branch, and M-PESA have gotten new investors excited about the sector’s potential. This frenzy of inclusive fintech activity has attracted well-known, marquee global investors such as Sequoia, Softbank’s Vision Fund, Silicon Valley Bank, and others to make their first major investments in companies headquartered in Africa. Nigeria’s Paystack was acquired by US Fintech Stripe in 2020 for $200M, the first large and high-profile purchase of an inclusive fintech provider, which demonstrated a path to exit and financial returns for investors. There are currently 6 African unicorns valued at $1bn or more, five of whom are fintech startups including Catalyst Fund’s Chipper Cash. The PayStack acquisition and the large rounds of the ‘unicorns’ have formed the Turning Point for inclusive fintech.

Map of key players, important moments, critical knowledge products and paradigm shifts for Inclusive Fintech

Key lessons from Inclusive Fintech’s transition from Irruption to Frenzy relevant for DF4CR:

- Funders catalyze the creation of early market data and intelligence, which can be used as a source of truth when assessing market potential for investors and innovators.

- Catalyst funders and governments must work together to create underlying tech and product infrastructure that innovators need as basic rails (e.g., digital ID, eKYC, zero-balance bank accounts, national data stack).

- Open sharing of customer insights can be valuable to increase awareness of harmful or predatory practices, and keep checks on customer protection practices from early in the ecosystem. Regulation and policy insights should be shared across countries (e.g. AFI) to ensure the design of safe and impactful solutions on a global scale.

- Incubation and acceleration models can help the industry understand new business models and de-risk startups for institutional investment.

- Creating industry awards and events (like Inclusive Fintech 50) can make a new ecosystem a discussion theme across major forums, local and global gatherings, and support the growth of high-profile global startups into emerging markets (e.g. YC, Google Launchpad).

- Alignment of early commercial risk-capital to drive and grow business models with clearly defined financial and non-financial parameters for success is needed from early in the ecosystem development.

- Regulatory sandboxes can help innovators test out solutions before going to market and using valuable resources to meet the compliance requirements and standards of larger institutions.

DF4CR in 2022 and beyond

The research and analysis detailed above informed the recommended actions in the DF4CR Framework for Action.

While this looking back exercise has been immensely useful in developing the framework, the DF4CR sector and this particular moment in time are unique for the emergence of innovation. In comparison to the other ecosystems, DF4CR will benefit from a much higher penetration and usage of mobile phones, internet connectivity, and mobile money compared to the other sectors – in fact, this higher penetration and usage is a result of the emergence of the other sectors. The increased use of internet and social media, even among lower income or rural populations, means there is more data and information available for things like risk profiling or alternative credit scoring.

Along with improvements in technology access and infrastructure, DF4CR will benefit from increasing pressure on governments and the private sector to invest in climate change solutions. There is a pressure at the policy level, along with large international and local capital commitments to improving climate resilience, so there are likely to be favorable market and regulatory conditions for DF4CR innovators as well as an abundance of de-risking capital for early stage innovators. In addition, the prior sectors have prepositioned a set of intermediaries like investment funds and accelerators, which are in a good position to channel the newly available capital towards innovators on the ground.

Finally, unlike the emergence of other sectors, we don’t have the liberty of time to test business models and experiment with proof of concepts over many years. Climate change is here, and its consequences are only projected to worsen in coming years.

The DF4CR ecosystem has already seen great progress in 2021. With a renewed sense of urgency and optimism, we look forward to launching an open ecosystem for innovation during 2022. For that we will need a network of interrelated components that propel the participating organizations towards concerted action, many of which are detailed in the Framework for Action that was developed based on this work.

The UN Race to Resilience has set a target to build the climate resilience of 4 billion people by 2030 to avoid the most catastrophic impacts of climate change on human life and well-being. DF4CR needs to build at speed on the lessons, technology, and rails developed by other ecosystems to move more quickly, efficiently, and inclusively towards Maturity.

[1] Though an uncommon English word, Irruption is the official word used by Carlota Perez in the Technological Revolutions framework